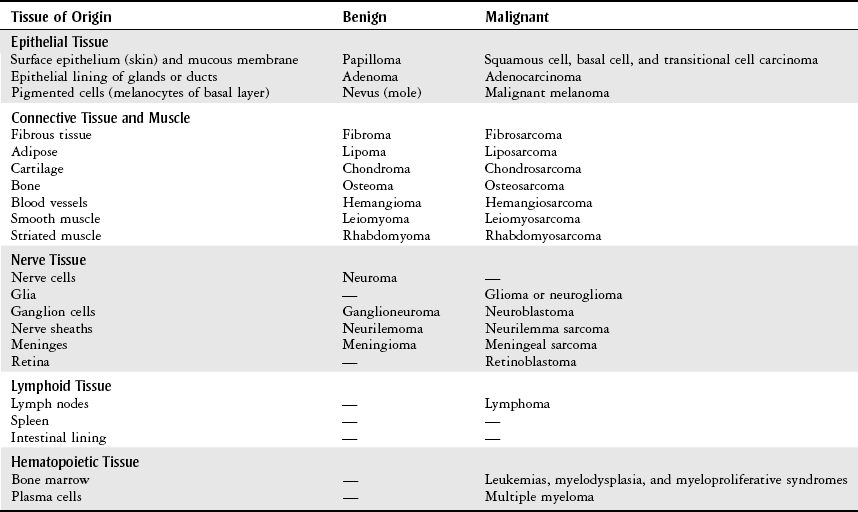

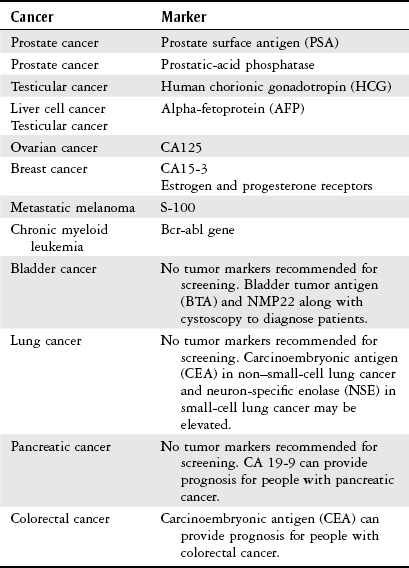

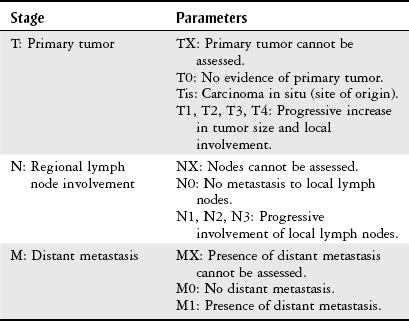

Chapter 11 The objectives for this chapter are to provide the following: 1 An understanding of the medical assessment and diagnosis of a patient with cancer, including staging and classification 2 An understanding of the various medical and surgical methods of cancer management 3 An overview of a variety of the different body system cancers, including common sites of metastases 4 Examination, evaluation, and intervention considerations for the physical therapist • Cancer (Including but Not Limited to Cancer of the Breast, Prostate, Lung, Colon, Oral, Uterine, Stomach): 4A, 4B, 4C, 5A, 6A, 6B, 6E • Kaposi’s Sarcoma: 6H, 7B, 7C, 7E Please refer to Appendix A for a complete list of the preferred practice patterns, as individual patient conditions are highly variable and other practice patterns may be applicable. Several terms are used in oncology to describe cancer or cancer-related processes, which are outlined in Table 11-1. Neoplasms, or persistent abnormal dysplastic cell growth, are classified by cell type, growth pattern, anatomic location, degree of dysplasia, tissue of origin, and their ability to spread or remain in the original location. Two general classifications for neoplasm are benign and malignant. Benign tumors generally consist of differentiated cells that reproduce at a higher rate than normal and are often encapsulated, allowing expansion, but do not spread to other tissues.1 Benign tumors are considered harmless unless their growth become large enough to encroach on surrounding tissues and impair their function. Malignant neoplasms, or malignant tumors, consist of undifferentiated cells, are uncapsulated, and grow uncontrollably, invading normal tissues and causing destruction to surrounding tissues and organs. Malignant neoplasms may spread, or metastasize, to distant sites of the body.1,2 Tumors may also be classified as primary or secondary. Primary tumors are the original tumors in the original location. Secondary tumors or cancers are metastases that have moved from the primary site.3 TABLE 11-1 Data from Stricker TP, Kumar V: Neoplasia. In Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N et al, editors: Robbins basic pathology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2007, Saunders, pp 174-175; National Cancer Institute: http://www.cancer.gov/dctionary. Accessed June 27, 2012; Gould B, Dyer R: Pathophysiology for the health professions, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders, p. 8. Benign and malignant tumors are named by their cell of origin (Table 11-2). Benign tumors are customarily named by attaching –oma to the cell of origin. Malignant tumors are usually named by adding carcinoma to the cell of origin if they originate from epithelium and sarcoma if they originate in mesenchymal tissue.2 Variations to this naming exist, such as melanoma and leukemia. TABLE 11-2 Classification of Benign and Malignant Tumors From Goodman CC: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders, p. 349. There are numerous carcinogens (cancer-causing agents) and risk factors that are thought to predispose a person to cancer. Most cancers probably develop from a combination of genetic and environmental factors. According to the American Cancer Society, cigarette smoking, heavy use of alcohol, physical inactivity, and being overweight or obese contribute to or cause several types of cancers. Infectious agents such as the hepatitis B virus (HBV), human papillomavirus (HPV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) have also been related to certain cancers such as cervical cancer (HPV).4 A complete overview of risk factors is beyond the scope of this text. As specific cancers are described later in the chapter, relevant etiological agents or risk factors are stated. Signs and symptoms of cancer are most often due to the tumor’s growth and invasion of surrounding tissues. Specific manifestations will depend on the particular cancer and body system(s) affected and are described later in the chapter in those respective sections. General signs and symptoms that may be indicative of early or progressive cancer include1,5: • Unusual bleeding or discharge • Unexplained weight loss of 10 pounds or more • Persistent cough or hoarseness without a known cause Paraneoplastic syndromes are symptoms that cannot be related directly to the cancer’s growth and invasion of tissues. They are thought to be due to abnormal hormonal secretions by the tumor. The syndromes are present in approximately 15% of persons diagnosed with cancer and often are the first sign of malignancy, represent significant clinical problems, and/or mimic metastatic disease. Clinical findings of paraneoplastic syndromes are similar to endocrinopathies (Cushing’s syndrome, hypercalcemia), nerve and muscle syndromes (myasthenia), dermatological disorders (dermatomyositis), vascular and hematological disorders (venous thrombosis, anemia), and many others.2 After obtaining a medical history and performing a physical examination, specific medical tests are employed to diagnose cancer. These tests may include medical imaging, blood tests for cancer markers, and several types of biopsy. Biopsy, or removal and examination of tissue, is the definitive test for cancer identification. Advancements in the technology of positron emission tomography (PET) scans in recent years have improved detection of cancer and subsequent management.6 Table 11-3 lists common medical tests used to diagnose cancer. Tumor markers that may help to provide a prognosis for patients who are diagnosed with certain cancers, as well possibly monitor response to treatment, are listed in Table 11-4. TABLE 11-3 TABLE 11-4 From American Cancer Society: Tumor markers. American Cancer Society website. http://www.cancer.org/Treatment/UnderstandingYourDiagnosis/ExamsandTestDescriptions/TumorMarkers/tumor-markers-common-ca-and-t-m. Updated March 24, 2011. Accessed August 10, 2011. The mostly commonly used method to stage cancer is the TNM system. Tumors are classified according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer, which bases this system on the extent (size and/or number) of the primary tumor (T), lymph nodes involvement (N), and presence or absence of metastasis (M) (Table 11-5).2,7 Certain types of cancers will have specific staging criteria, and these are identified later in this chapter for the various cancers. TABLE 11-5 From Stricker TP, Kumar V: Neoplasia. In Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N et al, editors: Robbins basic pathology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2007, Saunders, pp 174-223. Grading reports the degree of dysplasia, or differentiation, from the original cell type. Cells that are more highly differentiated resemble the original cells more strongly and this is associated with a lower grade and a less aggressive tumor. A higher grade is linked to aggressive, fatal tumors (Table 11-6). TABLE 11-6 From National Cancer Institute: cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/detection/tumor-grade. Accessed June 27, 2012; American Joint Committee on Cancer: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, ed 6, New York, 2002, Springer. • Surgical removal of the tumor • Biotherapy (including immunotherapy, hormonal therapy, bone marrow transplantation, and monoclonal antibodies) Surgical intervention is determined by the size, location, and type of cancer, as well as the patient’s age, general health, and functional status. Successful localization and resection of recurrent and/or metastatic lesions found on PET positive scans may be optimized with the intraoperative use of a hand-held PET probe.8 The following are indications for invasive surgical management9: • Removal of precancerous lesions or of organs at high risk for cancer • Establishing a diagnosis by biopsy • Assisting in staging by sampling lymph nodes • Definitive treatment by removing the primary tumor • Reconstruction of a limb or organ with or without skin grafting • Palliative care such as decompressive or bypass procedures Specific surgical procedures relevant to musculoskeletal and neurological cancers are discussed in Chapters 5 and 6, respectively. Additional surgical procedures for specific cancers are covered later in the chapter. The primary objective in administering radiation therapy10,11 is to eradicate tumor cells, either benign or malignant, while minimizing damage to healthy tissue. This objective can further be divided into six different indications based on the disease presentation and practitioner’s intentions: 1. Definitive treatment with the intent to cure 2. Neoadjuvant treatment to improve chances of successful surgical resection 3. Adjuvant treatment to improve local control of cancer growth after chemotherapy or surgery 4. Prophylactic treatment to prevent growth of cancer in asymptomatic, yet high-risk areas for metastasis 5. Control to limit growth of existing cancer cells 6. Palliation to relieve pain, prevent fracture, and enhance mobility when cure is not possible Before a patient receives radiation therapy, a simulation procedure is performed in order to circumscribe the tumor and adjacent tissues and organs to prepare for delivery of ionizing radiation. Simulation can be performed with computed tomography (CT), virtual simulation software, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Further mapping is then performed to synchronize the radiation energy with the patient’s respiratory cycle, and PET scanning is also used to specifically map the tumor.12 Radiation therapy is delivered by three different modalities: external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), brachytherapy, or radioimmunotherapy (RIT). EBRT is the primary modality used in most cases. Technological advances have allowed EBRT to be further divided into different modalities that allow better localization of tumor margins along with gradation of radiation dose, both of which can minimize damage to surrounding tissues and maximize therapeutic effect. These different forms of EBRT include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT), stereotactic radiosurgery, and image-guided cyberknife radiosurgery.10,12 Brachytherapy involves the placement (temporary or permanent) of selected radioactive sources directly into a body cavity (intracavitary), into tissue (interstitial), into passageways (intraluminal), or onto tissue surfaces (plaque).12 The following malignancies can be treated with brachytherapy: gynecological, breast, lung, esophageal, head and neck, brain, and prostate tumors, as well as certain types of melanoma. Brachytherapy can be used alone or in combination with EBRT. Another form of radiation therapy, intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT), consists of delivering a single, large fraction of radiation to an exposed tumor or to a resected tumor bed during a surgical procedure. IORT is generally used in the management of gastrointestinal, genitourinary, gynecological, and breast cancers.10 Advances in radiation therapy include using high-intensity focused ultrasound with magnetic resonance guidance (MRgFUS) and selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT).12 General side effects that commonly occur with radiation therapy include skin reactions, fatigue, weight loss, and myelosuppression (bone marrow suppression). Numerous site-specific toxicities may include limb edema, alopecia, cerebral edema, seizures, visual disturbances, cough, pneumonitis, fibrosis, esophagitis, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cystitis, and cardiomyopathy. These side effects may occur immediately after radiation therapy and/or reappear at a later time. In addition, radiation-induced malignancies may occur, including breast cancer, leukemia, and sarcoma.13 The overall purpose of chemotherapy is to inhibit various signaling pathways that control cancer cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, and cell death. Chemotherapy agents can potentially provide a cure or manage metastatic disease and reduce the size of the tumor for surgical resection or palliative care.14 Chemotherapy can be performed preoperatively and postoperatively. Chemotherapy is usually delivered systemically, via intravenous or central lines, but may be directly injected in or near a tumor. Refer to Chapter 18, Table 18-7 for information regarding totally implantable intravascular catheters or tunneled central venous catheters often used for chemotherapy. Patients may receive a single or multiple rounds of chemotherapy over time to treat their cancer and to possibly minimize side effects. Side effects of chemotherapy include nausea, vomiting, “cancer pain,” and loss of hair and other fast-growing cells, including platelets, red blood cells, and white blood cells. A variety of chemotherapy agents have different mechanisms of action and are described in Chapter 19, Table 19-23. • Nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy vary on a patient-to-patient basis. The severity of these side effects may be due to the disease stage, chemotherapeutic dose, or number of rounds. Some side effects may be so severe as to limit physical therapy, whereas others allow patients to tolerate activity. Rehabilitation should be delayed or modified until the side effects from chemotherapy are minimized or alleviated. • Patients may be taking antiemetics, which help to control nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy. The physical therapist should alert the physician when nausea and vomiting limit the patient’s ability to participate in physical therapy so that the antiemetic regimen can be modified or enhanced. Antiemetics are listed in Chapter 19, Table 19-22. • Chemotherapy agents affect the patient’s appetite and ability to consume and absorb nutrients. This decline in nutritional status can inhibit the patient’s progression in strength and conditioning programs. Proper nutritional support should be provided and directed by a nutritionist. Consulting with the nutritionist may be beneficial when planning the appropriate activity level based on a patient’s caloric intake. • Patients should be aware of the possible side effects and understand the need for modification or delay of rehabilitation efforts. Patients should be given emotional support and encouragement when they are unable to achieve the goals that they have initially set. Intervention may be coordinated around the patient’s medication schedule. • Vital signs should always be monitored, especially when patients are taking the more toxic chemotherapy agents that affect the heart, lungs, and central nervous system. • Platelet, red blood cell, and white blood cell counts should be monitored with a patient on chemotherapy. The Stem Cell Transplantation section in Chapter 14 suggests therapeutic activities with altered blood cell counts. • Patients receiving chemotherapy can become neutropenic and are at risk for infections and sepsis.15 (A neutrophil is a type of leukocyte or white blood cell that is often the first immunological cell at the site of infection; neutropenia is an abnormally low neutrophil count. Absolute neutrophil count [ANC] will determine whether or not a patient is neutropenic and subsequent precautions.) Therefore patients undergoing chemotherapy may be on neutropenic precautions, such as being in isolation. Follow the institution’s guidelines for precautions when treating these patients to help reduce the risk of infections. Examples of these guidelines can be found in the Stem Cell Transplantation section in Chapter 14. Biological therapy, also referred to as immunotherapy, uses a patient’s native host defense system as mechanisms to treat cancer. This form of therapy can be highly targeted while minimizing toxicity. Agents currently used for biotherapy include cytokines, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines.16 Chapter 19, Table 19-23 provides a list of cytokines and monoclonal antibodies used for cancer management as well as their side effects and physical therapy considerations. Vaccines are currently used to prevent viral infections that have been shown to lead to cancer. Human papillomavirus has been linked to cervical cancer, and hepatitis B can lead to liver cancer. Vaccination is available for both of these pathogens.17 The potential exists for treating many genetic disorders as well as autoimmune disorders, cancer, and infectious diseases by genetically modifying cells that may have defective genetic material. A common therapeutic approach is performed by introducing normal genes into a patient’s cell nuclei in order to enhance, repair, or replace altered genetic material. Somatic gene therapy is approved in the United States and involves somatic, nonreproductive cells of the body including skin, muscle, bone, and liver.18 Cancer can affect any structure of the respiratory system, including the larynx, lung, and bronchus. There are two major categories of lung cancer, non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). Approximately 85% of lung cancers are NSCLC, which is composed of three subtypes: squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma.19,20 The risk of developing lung cancer is 13 to 23 times higher, respectively, in female and male smokers as compared to nonsmokers. Eighty percent of lung cancer deaths are related to smoking.4 Symptoms associated with lung cancer include chronic cough, dyspnea, hoarseness, chest pain, and hemoptysis. Additional symptoms may also include weakness, weight loss, anorexia, and, rarely, fever.20 Common sites of metastases for lung cancer include bone, adrenal glands, liver, intraabdominal lymph nodes, brain and spinal cord, and skin (20%).20,21 Bronchoscopy, biopsy, and imaging techniques such as radiography, CT, and PET can be used to stage lung cancer.20–22 In addition to the TNM staging, NSCLC is further staged to help guide interventions and prognosis. Table 11-7 outlines the specific TNM components, and Table 11-8 illustrates the staging components from Ia to IV. TABLE 11-7 Staging of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer *T2 tumors with these features are classified as T2a if ≤5 cm. †The uncommon superficial spreading tumor in central airways is classified as T1. ‡Pleural effusions are excluded that are cytologically negative, nonbloody, transudative, and clinically judged not to be due to cancer. From Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Tanoue LT: The new lung cancer staging system, Chest 136(1):260, 2009.

Oncology

Preferred Practice Patterns

Terminology

Term

Definition

Neoplasm

“New growth” pertaining to an abnormal mass of tissue that is excessive, persistent, and unregulated by physiological stimuli.

Tumor

Common medical language for a neoplasm.

Cancer

A term for diseases in which abnormal cells divide without control and can invade nearby tissues. Malignant tumors are referred to as cancers.

Dysplasia

Variability of cell size and shape with an increased rate of cell division (mitosis). This situation may be a precancerous change or result from chronic infection.

Metaplasia

Replacement of one mature cell type by a different mature cell type, resulting from certain stimuli such as cigarette smoking.

Hyperplasia

An increased number of cells resulting in an enlarged tissue mass. It may be a mechanism to compensate for increased demands, or it may be pathological when there is a hormonal imbalance.

Differentiation

The extent to which a cell resembles mature morphology and function. A cell that is well differentiated is physiological and functions as intended. A poorly differentiated cell does not resemble a mature cell in both morphology and function.

Nomenclature

Risk Factors

Signs and Symptoms

Diagnosis

Test

Description

Biopsy

Tissue is taken via incision, needle, or aspiration procedures. A pathologist examines the tissue to identify the presence or absence of cancer cells; if cancer is present, the tumor is determined to be benign or malignant. The cell or tissue of origin, staging, and grading are also performed.

Stool guaiac

Detects small quantities of blood in stool.

Pap smear

A type of biopsy in which cells from the cervix are removed and examined.

Sputum cytology

A sputum specimen is inspected for cancerous cells.

Sigmoidoscopy

The sigmoid colon is examined with a sigmoidoscope.

Colonoscopy

The upper portion of the rectum is examined with a colonoscope.

Bronchoscopy

A tissue or sputum sample can be taken by rigid or flexible bronchoscopy.

Mammography

A radiographic method is used to look for a mass or calcification in breast tissue.

Radiography

X-ray is used to detect a mass.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT)

These noninvasive imaging techniques are used to localize lesions suspected of being cancerous.

Bone scan

Radionuclide imaging used to detect the presence, amount of metastatic disease, or both in bones.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

An imaging technique that uses radionuclides that emit positively charged particles (positrons) injected into the body, followed by imaging, to detect subtle changes in metabolic and chemical activity within the body. Can be combined with CT scanning. Currently used to help detect biopsy location, discern benign versus malignant conditions, stage disease, and diagnose cancer recurrence.

Staging and Grading

Grade

Description

GX

Undetermined grade, cannot be assessed

G1

Low grade, well-differentiated tumor

G2

Intermediate grade, moderately differentiated tumor

G3

High grade, poorly differentiated tumor

G4

High grade, undifferentiated tumor

Management

Surgery

Radiation Therapy

Chemotherapy

Physical Therapy Considerations

Biotherapy

Gene Therapy

Cancers in the Body Systems

Respiratory Cancers

Descriptors

Definitions

T

Primary tumor

T0

No primary tumor

T1

Tumor ≤3 cm in the greatest dimension, surrounded by lung or visceral pleura, not more proximal than the lobar bronchus

T1a

Tumor ≤2 cm in the greatest dimension

T1b

Tumor >2 but ≤3 cm in the greatest dimension

T2

Tumor >3 but ≤7 cm in the greatest dimension or tumor with any of the following*:

Invades visceral pleura

Involves main bronchus ≥2 cm distal to the carina†

Atelectasis/obstructive pneumonia extending to hilum but not involving the entire lung

T2a

Tumor >3 but ≤5 cm in the greatest dimension

T2b

Tumor >5 but ≤7 cm in the greatest dimension

T3

Tumor >7 cm; or directly invading chest wall, diaphragm, phrenic nerve, mediastinal pleura, or parietal pericardium; or tumor in the main bronchus <2 cm distal to the carina†; or atelectasis/obstructive pneumonitis of entire lung; or separate tumor nodules in the same lobe

T4

Tumor of any size with invasion of heart, great vessels, trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve, esophagus, vertebral body, or carina; or separate tumor nodules in a different ipsilateral lobe

N

Regional lymph nodes

N0

No regional node metastasis

N1

Metastasis in ipsilateral peribronchial and/or perihilar lymph nodes and intrapulmonary nodes, including involvement by direct extension

N2

Metastasis in ipsilateral mediastinal and/or subcarinal lymph nodes

N3

Metastasis in contralateral mediastinal, contralateral hilar, ipsilateral or contralateral scalene, or supraclavicular lymph nodes

M

Distant metastasis

M0

No distant metastasis

M1a

Separate tumor nodules in a contralateral lobe; or tumor with pleural nodules or malignant pleural dissemination‡

M1b

Distant metastasis

Special situations

TX, NX, MX

T, N, or M status not able to be assessed

Tis

Focus of in situ cancer

T1†

Superficial spreading tumor of any size but confined to the wall of the trachea or mainstem bronchus

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Oncology

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue