CHAPTER TWO Principles of Therapeutic Exercise Design

This chapter describes the underlying principles for designing a therapeutic exercise programme. Treatment goals, adherence, safety and training principles are addressed. Specific considerations such as motor learning, physical principles and starting positions are discussed.

THERAPEUTIC EXERCISE

‘Physical activity is any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in an expenditure of energy’ (www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/physical/terms/). Examples of physical activity could include housework, walking, dancing, gardening or exercise.

‘Exercise is physical activity that is planned or structured. It involves repetitive bodily movement done to improve or maintain one or more of the components of physical fitness – cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility and bodily composition’ (www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/physical/terms/).

DESIGNING A THERAPEUTIC EXERCISE PROGRAMME

Identifying treatment goals

Once this information has been obtained, the main problems to be addressed can be identified. Treatment goals should be set with the patient. The range of appropriate exercise options should be discussed with the patient so that they can make an informed decision in collaboration with the physiotherapist about what would be the best treatment for them. Any treatment goals which are set should be SMART – specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely – for the patient concerned. Setting agreed goals with patients will improve their adherence to the exercises.

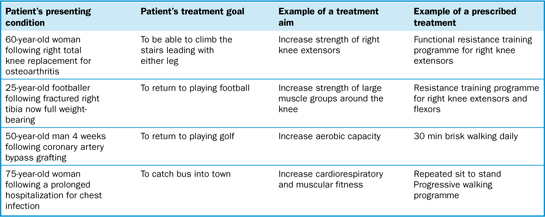

Table 2.1 shows some examples of treatment goals.

Stages of rehabilitation

As a patient progresses through their exercise programme, they may pass through early, intermediate and late stages of rehabilitation. This will most commonly be true of patients who have had an acute illness or injury from which they are expected to recover. These stages of rehabilitation correspond to the healing process and the common symptoms with which the patient may present. Therefore there will be common features as to the type of exercises which are most suitable for the patient at a particular stage of rehabilitation. Moving through the stages of rehabilitation can signify important steps in progress for the patient; for example a patient who has fractured their tibia may be able to move from non-weight-bearing in the early stage of rehabilitation to partial weight-bearing in the intermediate stage. More detail about the stages of rehabilitation can be found in Chapter 11.

Common training principles

Overload

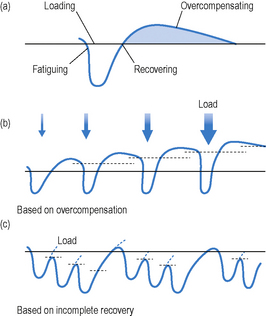

A system must be exercised at a level beyond which it is presently accustomed for a training effect to occur. The system being exercised will gradually adapt to the overload or training stimulus being applied, and this will go on happening as long as the training stimulus continues to be increased until the tissue can no longer adapt. The training stimulus applied consists of different variables such as intensity, duration and frequency of exercise. It is important to give the system being exercised enough time to recover and only apply a training stimulus again when the system is no longer fatigued. Loading a fatigued system will not result in a training effect. This is illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Specificity

Any exercise will train a system for the particular task being carried out as the training stimulus. This means that, for example, a training programme including muscle strengthening will train the muscle in the range that it is working and the way that the muscle is being used, i.e. isometrically, concentrically or eccentrically. It is important that any exercise to strengthen muscle targets the muscle range and type of muscle work specific to the task required. For example, riding a bicycle requires concentric knee extension from mid- to inner range, as the pedal is pushed down to propel the bicycle along. A cyclist wishing to increase the strength of his quadriceps will need to train concentrically in mid- to inner range. Depending on the presenting problem, the required task should become part of the training programme at an appropriate stage.

Individuality

Variation in response to a training programme will occur in a population as people respond differently to the same training programme. This response can be explained by the initial fitness level of the individual, their health status and their genetic makeup. Training programmes should be designed to take this into account. Some individuals will have a predisposition to endurance training and some to strength training. Some will respond well to a training programme and others much more slowly. Those individuals with a lower fitness level before starting an exercise programme show improvement in fitness more quickly than those who are relatively fit before training begins. Some individuals with health conditions may not be able to work at the same kind of intensity as a healthy individual and so will take longer to achieve a training goal.

Safety

Whenever an individual exercises there is a risk that they may injure themselves. Safety factors are considered here in relation to the physiotherapist, the environment and the patient or person carrying out the exercise.

have a knowledge and understanding of pathology, physiology, psychology and the evidence base relating to exercise prescription

have a knowledge and understanding of pathology, physiology, psychology and the evidence base relating to exercise prescription carry out a thorough assessment of the patient to identify factors that will affect the exercise prescription, such as age, health status and how much activity the person is normally accustomed to

carry out a thorough assessment of the patient to identify factors that will affect the exercise prescription, such as age, health status and how much activity the person is normally accustomed to be able to assess the risk involved with a person doing a particular exercise and adapt the exercise appropriately, e.g. provide support for an unsteady person carrying out an exercise that involves challenging their balance

be able to assess the risk involved with a person doing a particular exercise and adapt the exercise appropriately, e.g. provide support for an unsteady person carrying out an exercise that involves challenging their balance be able to teach the patient how to carry out the exercise correctly; this may involve breaking down the activity into parts initially and then allowing the patient time to practise, with adequate supervision and feedback, until they can perform the activity

be able to teach the patient how to carry out the exercise correctly; this may involve breaking down the activity into parts initially and then allowing the patient time to practise, with adequate supervision and feedback, until they can perform the activityStay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree