Chapter 9 Occupational therapy

Treatment options in rheumatology

KEY POINTS

The role of the occupational therapist in rheumatology is to: improve a person’s ability to perform daily tasks and valued life roles; facilitate successful adaptation to disruption in lifestyle, prevent loss of function and improve or maintain psychological status

The role of the occupational therapist in rheumatology is to: improve a person’s ability to perform daily tasks and valued life roles; facilitate successful adaptation to disruption in lifestyle, prevent loss of function and improve or maintain psychological status With its focus on occupational performance the link between biological, psychological, social factors and activity is central to OT interventions which are characterized by a patient centred approach

With its focus on occupational performance the link between biological, psychological, social factors and activity is central to OT interventions which are characterized by a patient centred approach Interventions are informed by the use of accurate and timely assessment to identify areas of activity limitation of relevance to the individual

Interventions are informed by the use of accurate and timely assessment to identify areas of activity limitation of relevance to the individual Some of the main approaches used by occupational therapists focus on improving occupational performance by:

Some of the main approaches used by occupational therapists focus on improving occupational performance by: Occupational therapists play a central role in enabling people with rheumatic diseases to remain in employment for as long as possible.

Occupational therapists play a central role in enabling people with rheumatic diseases to remain in employment for as long as possible.INTRODUCTION

Occupational therapy aims to help a person with a rheumatic disease be who they want to be and do the things they want to do, need to do or are expected to do (Law et al 2005). The role of the occupational therapist in rheumatology is to: improve a person’s ability to perform daily tasks and valued life roles; facilitate successful adaptation to disruption in lifestyle, prevent loss of function and improve or maintain psychological status (College of Occupational Therapists 2003). This is achieved by promoting health and well being through occupation across the life course. This chapter will explore some of the primary interventions used by occupational therapists to achieve this aim focusing on key occupational roles.

THE IMPACT OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS ON OCCUPATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Longitudinal cohort studies of people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) highlight its significant impact in terms of activity limitation with up to 49% of participants experiencing moderate disability after 10 years (Symmons & Silman 2006, Wolfe 2000). Whilst the model of progressive disability suggests that this occurs as a consequence of disease over time, recent work has questioned this linear model. Some evidence suggests that most disability occurs in the first 3 years of diagnosis whilst the work by Wolfe suggests that, on an individual basis, the impact of RA on activity limitation may be more variable and chaotic and less linear (Wolfe 2000). Routine assessment of activity is important therefore to identify early when activity limitation starts to occur in a person’s illness trajectory.

Many studies provide insights into the significant challenges faced by people living with rheumatic diseases in terms of its impact on all areas of activity. Longitudinal studies suggest that over a five year period people with RA can lose the ability to undertake 10% of the activities they value (Katz 1995). Approximately one-third of people with RA report stopping work within 3 years of being diagnosed (Young et al 2000) and leisure activities are also affected profoundly. Fex et al 1998 found that 75% of the 106 patients in their study had to alter leisure time activities and 50% were not satisfied with their recreation.

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY MANAGEMENT

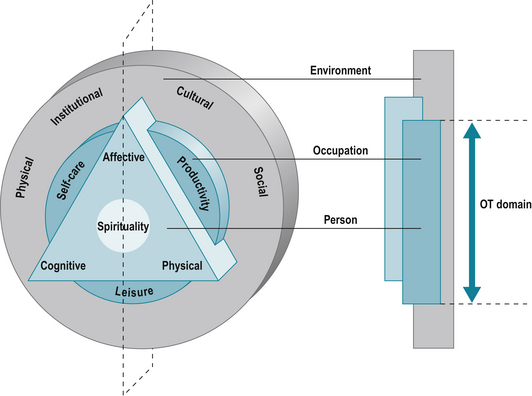

Theoretical models underpinning occupational therapy such as the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists 1997) (Fig. 9.1), the Person Environment Occupational Performance Model (Christiansen et al 2005), the Model of Human Occupation (Kielhofner 2002) and the newer Kawa model (Iwama 2006) are aligned closely to the biopsychosocial model described in chapter 5. With its focus on occupational performance the link between biological, psychological, social factors and activity is central to OT interventions which are characterised by a patient centred approach.

Figure 9.1 The Canadian Occupational Performance Model.

Reproduced from The Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement. In: Townsend E, Polatajko H (2007) Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, Well-being & Justice through Occupation. CAOT Publications ACE, Ottawa, ON p. 23 with permission of CAOT Publications ACE.

THE EVIDENCE BASE

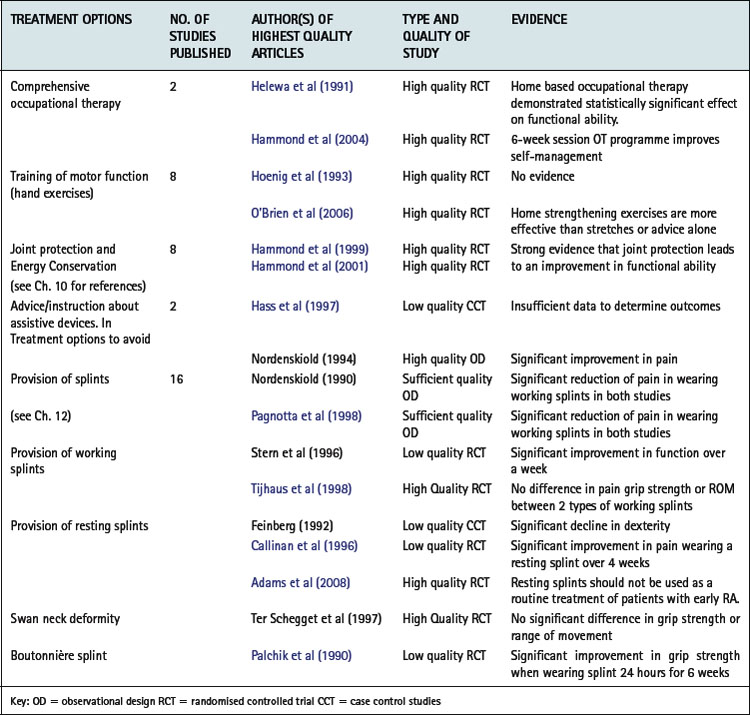

There is a growing body of evidence relating to the efficacy of occupational therapy interventions which allows therapists, clinicians and managers as well as the service user to make informed decisions about the best treatment options and design their interventions and services accordingly. Steultjens et al (2004) found varying degrees of evidence for the effectiveness of occupational therapy (Table 9.1), most of which is derived from work undertaken with people with inflammatory arthritis. Some areas of practice, such as work and leisure, remain under evaluated and further research is required in these areas.

ASSESSMENT OF ACTIVITY LIMITATION

Assessment is fundamental to the planning of interventions and the evaluation of their efficacy. The focus of assessments used by occupational therapists is on identifying areas of activity limitation defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as difficulties an individual may have in executing activity (WHO 2001). Assessment of activity limitation can broadly be categorised as the use of standardized assessments and the use of structured interviews.

STANDARDIZED ASSESSMENT

Many of the quality of life assessments used in rheumatology incorporate subscales for activities of daily living alongside measures of psychological well-being and symptoms. For example, the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale 2 (AIMS2) has subscales assessing physical activity, dexterity, household activity, social activities and activities of daily living (Meenan et al 1992). Some measures focus specifically on activity limitation and have been developed for use with a number of different rheumatic diseases e.g. the Disability Index of the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (Fries et al 1980). Others are disease specific, such as the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (Calin et al 1994).

Whilst some assessments, such as the HAQ, cover a broad range of activities others focus on specific domains of activity, e.g. The Rheumatoid Arthritis Work Instability Scale (Gilworth et al 2003) or the Parenting Disability Indices (Katz et al 2003). These may be used as an additional assessment when more detailed information is required about a specific area of activity limitation. Other measures focus on activity limitation associated with specific regions of the body, such as the Oxford Hip Score (Dawson et al 1996) or The Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand (Hudak et al 1996).

Standardized assessments have been evaluated extensively to ensure that they are valid, (measuring what they claim to measure), reliable (are as accurate as possible) and sensitive to change (able to detect change when change has occurred). Many of the measures described above are self-complete questionnaires comprising a range of predefined activities against which a person rates the level of difficulty they experience when completing each activity. However some assessment may include observation or assessment of a person completing specific activities. Others incorporate an element of measurement such as grip strength or range of movement, e.g. The Jebsen Test of Hand Function (Jebsen et al 1969). Whilst standardized measures have demonstrated efficacy in clinical and research contexts one of the criticisms of their use in a clinical context is their inability to capture activities which are important to clients (Hewlett 2003).

A recent development has been the patient generated index which enables each person to identify areas of activity limitation of greatest concern to them. Two examples relevant to activity limitation are the MACTAR Patient Preference Disability Questionnaire (Tugwell et al 1987) and the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) (Law et al 1990, 2005). The COPM is informed by a semi-structured interview during which people are asked to identify areas of activity limitation and rank them in order of importance. For the top five activities, they rate their current performance of the activity and satisfaction with their current performance. These activities inform the treatment programme and the person is reassessed to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention. The COPM is congruent with a person centred approach and does not constrain the activities a client can identify (see Ch. 4 for further information on patient reported outcome measures).

THE IMPACT OF RHEUMATIC DISEASES ON SELF CARE AND HOUSEHOLD ACTIVITIES

The loss of ability to perform activities of daily living is one of the most documented consequences of rheumatic diseases (Symmons & Silman 2006, Wolfe 2000). Sokka et al (2003) demonstrated that patients with rheumatoid arthritis have a 7-fold risk of functional disability in self care activities as measured by the HAQ compared to the normal population.

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY INTERVENTIONS

The strongest evidence in rheumatology occupational therapy is also informed by the impact of interventions on activities of daily living (Hammond et al 1999, 2001, Helewa et al 1991). Some of the main approaches used by occupational therapists focus on improving occupational performance by:

Using alternative methods

The development of skills in joint protection and energy conservation is one of the main occupational therapy interventions to maintain levels of activity and is described in chapter 10.

Using assistive devices

People with arthritis are one of the largest user groups of assistive devices (Rogers & Holmes 1992). These are used to:

Devices are usually provided on a permanent basis but, in some instances, may only be required for a short period, e.g. post joint replacement surgery. Studies suggest that up to a third of devices provided remain unused (Scherer 2002). A number of factors contribute to non-use, such as changes in the person’s condition, the impact of comorbidities, lack of involvement in the assessment process, inadequacy of the device, embarrassment and a preference for person assistance (Wielandt & Strong 2000). Therefore, careful assessment is required considering factors relevant to:

Figure 9.2 Key factors to consider when assessing for assistive technology.

(adapted from the Trusted Assessor Framework Winchcombe & Ballinger 2005)

Adapting the environment

As people develop an understanding of the problems associated with living with arthritis they often make changes to their home environment when undertaking renovation work. For example, installing lever taps, easier door handles and locks, raising electric sockets, designing easily accessible and energy saving kitchens, raising toilet height and installing a downstairs toilet (see Box 9.1 and Fig. 9.3).

BOX 9.1 Additional resources related to assistive devices and adaptations

Disabled Living Foundation: provides information and advice about assistive devices and a wide range of fact sheets can be downloaded from their website. The DLF also produces DLF Data the main national database for assistive devices.

Disabled Living Foundation: provides information and advice about assistive devices and a wide range of fact sheets can be downloaded from their website. The DLF also produces DLF Data the main national database for assistive devices.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree