Oblique First Metatarsal Osteotomy: Ludloff

Hans-Joerg Trnka

Reinhard Schuh

There is no shortage of opinions regarding the optimal surgical treatment of moderate or severe hallux valgus. Most agree that distal metatarsal osteotomies and phalangeal osteotomies are not as effective as more proximal operations. In 1918, Ludloff (1) described an oblique osteotomy from the dorsal-proximal to the plantar-distal aspect of the first metatarsal, and the procedure was originally performed without internal fixation. The technique was modified subsequently, and in recent years, there has been renewed interest in the operation (2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7). One modification is the use of contemporary fixation, such as multiple screws. A more proximal screw can be inserted without fully tightening it before completing the osteotomy at the plantar cortex and inserting a second screw. In this manner, the osteotomy remains more stable throughout the procedure, and the 1-2 intermetatarsal angle (IMA) is corrected. Several investigators reported that the osteotomy fixed with two screws was more rigid than other proximal procedures fixed with a single screw as proximal chevron and proximal crescentic osteotomies (7).

The operation is combined with distal soft tissue realignment (DSTR). The DSTR alone is often not adequate for correction of hallux valgus, particularly with more advanced deformities. Combined with the oblique metatarsal osteotomy, the correction of severe malalignment is possible.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The primary indication for proximal metatarsal osteotomy combined with a distal soft tissue procedure is pain over the medial eminence. The pain in the medial forefoot is mainly related to the use of enclosed shoes. Other common complaints are painful second hammertoe and metatarsalgia under the second metatarsal head. The operation is indicated for hallux valgus deformity with an intermetatarsal 1-2 angle of 15° or more. In case of failure of treatment with appropriate footwear, this operation is indicated. The operation is appropriate for hallux valgus with a subluxated or noncongruent metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint.

Age does not seem to be a contraindication for this procedure; however, when severe osteopenia is present, the procedure should be reconsidered due to possible failure of usual internal fixation. While not all patients older than 65 years of age are osteopenic, Trnka et al. observed an increased incidence of osseous callus at the osteotomy site in patients older than 65 years of age when compared with younger patients.

Contraindications include symptomatic osteoarthritis of the first MTP joint. Metatarsocuneiform hypermobility is a contraindication, and fusion of the first metatarsocuneiform joint may be necessary in this uncommon situation. Neuropathy, active infection, peripheral vascular disease, and significant metatarsus adductus are contraindications. Tobacco use represents a relative contraindication. A patient who has no pain but is concerned with the cosmetic appearance should be encouraged to defer surgery unless pain becomes a major complaint. The examiner should be aware of the patient’s occupation, footwear requirements, and athletic activity because certain stressful physical activities may not be compatible with a successful surgical result. An athlete may find minor

postoperative restricted range of motion much more annoying than the preoperative discomfort that led her or him to surgery. Prior hallux valgus surgery is not necessarily a contraindication, and this procedure may be used to salvage a previous surgical failure.

postoperative restricted range of motion much more annoying than the preoperative discomfort that led her or him to surgery. Prior hallux valgus surgery is not necessarily a contraindication, and this procedure may be used to salvage a previous surgical failure.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Planning for Ludloff metatarsal osteotomy includes a patient history, examination of the foot, general health evaluation, radiologic interpretation, and consideration of appropriate patient expectations. Clinical examination includes measuring hallux MTP joint range of motion, symptoms associated with hallux motion, first tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint stability, and lesser metatarsal head plantar callosities (indicative of transfer metatarsalgia). The foot is examined with the patient in a sitting and standing position and inspected for pes planus, intractable plantar keratosis, other areas of callous formation, and lesser toe deformities. The skin overlying the medial eminence is assessed for blistering or potential skin breakdown. Range of motion of the hallux is evaluated, and the magnitude of pronation of the great toe is assessed. Dynamic plantar foot pressure assessment may be useful. The neurovascular status of the foot should be documented. If posterior tibial and dorsal pedis pulses are not palpable, additional investigations is warranted, such as Doppler examination or noninvasive vascular studies.

Weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the foot are obtained. From these radiographs, the angular relationships that identify the presence and determine the magnitude of the deformities of the bones and the joints associated with hallux valgus are measured. Other conditions, such as instability, osteoarthritis, and malalignment of joints elsewhere in the foot or the manifestations of vascular, neurogenic, or systemic disorders that affect the function of the foot, also may be appreciated. Oblique views of the foot may facilitate the recognition of these associated problems; however, they are not used to measure any of conventional parameters of alignment. Weight-bearing sesamoid views may help in preoperative planning. The sesamoid bones can appear laterally displaced on weight-bearing AP foot views in congruent hallux valgus but rest in their respective facets on the axial sesamoid view.

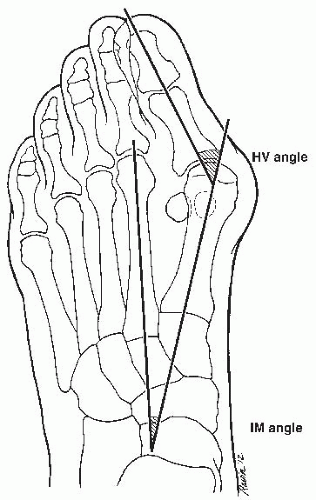

The hallux valgus angle (HVA), defined as the angle formed by the intersection of longitudinal axes of the diaphyses of the first metatarsal and the proximal phalanx, quantifies the malalignment of the first MTP joint (Fig. 7.1). The upper limit of normal for this measurement is about 15°. The 1-2 IMA represents the angle formed between the diaphysis of the first and second metatarsals. This measurement quantifies the extent of metatarsus primus varus. The upper limit of normal for IMA is about 9°. Patients with severe hallux valgus deformity with IMA of more than 15° as candidates for the Ludloff osteotomy. If the deformity is mild or moderate, a distal metatarsal osteotomy should be considered.

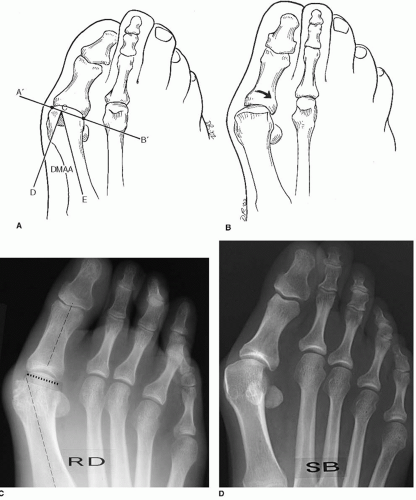

The distal metatarsal articular angle (DMAA) assesses the angular relationship between the articular surface of the head and diaphysis of the first metatarsal (Fig. 7.2). The normal DMAA

is 0° to 8°. The DMAA relates the inclination of the metatarsal head articular surface to the longitudinal axis of the first metatarsal. When a significant DMAA is present, an attempt with the usual operative techniques to realign the proximal phalanx on the laterally inclined metatarsal articular surface can create an abnormal articulation that may eventually result in recurrence of deformity, MTP joint stiffness, or degenerative osteoarthritis of the first MTP joint. This condition is uncommon, but it should be recognized, and if it is present, the Ludloff procedure is contraindicated.

is 0° to 8°. The DMAA relates the inclination of the metatarsal head articular surface to the longitudinal axis of the first metatarsal. When a significant DMAA is present, an attempt with the usual operative techniques to realign the proximal phalanx on the laterally inclined metatarsal articular surface can create an abnormal articulation that may eventually result in recurrence of deformity, MTP joint stiffness, or degenerative osteoarthritis of the first MTP joint. This condition is uncommon, but it should be recognized, and if it is present, the Ludloff procedure is contraindicated.

FIGURE 7.1 The HVA is the magnitude of the angular deformity at the first MTP joint. The 1-2 IMA is the magnitude of divergence between the first and second metatarsals. |

The forefoot is inspected for the presence of significant metatarsus adductus. A significant hallux valgus deformity may occur even if the IMA is measured is within the normal range because of significant metatarsus adductus. In this situation, a standard operation for mild to moderate deformity may not adequately realign the first ray and recurrence is common.

In a normal foot without deformity, the sesamoids are located beneath the metatarsal head. With increasing deformity, the fibular sesamoid lies exposed or uncovered on an AP radiograph and is seen along the lateral border of the first metatarsal head. The magnitude of this exposure depends on the severity of the hallux valgus deformity and the amount of pronation of the great toe. To achieve a successful and stable correction of a hallux valgus deformity, an attempt must be made to correct all elements of the deformity present, including an increased 1-2 IMA, an increased HVA, a prominent medial eminence, sesamoid subluxation, and pronation of the great toe. Incomplete correction of these elements may lead to recurrence of the deformity.

Most hallux valgus operations are performed at the distal metatarsal level. Techniques of more proximal level metatarsal osteotomy include a crescentic osteotomy, opening wedge and closing wedge osteotomy, proximal chevron osteotomy, and Scarf osteotomy. A closing or opening wedge osteotomy alters the metatarsal length. An oblique Ludloff osteotomy can correct an increased 1-2 IMA without significantly altering the length of the first metatarsal. The long oblique osteotomy has the potential of correcting severe deformity and it provides a broad contact area that is characterized by rapid healing because of its large surface area.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The procedure is performed with the patient under regional anesthesia (ankle block with 1% Xylocaine (lidocaine) and 0.5% bupivacaine), supine position.

The use of fluoroscopy to monitor alignment and fixation is recommended.

The foot is exsanguinated with an Esmarch bandage. Padding is placed around the ankle, and the Esmarch bandage is used as a tourniquet. With peripheral anesthesia, the patient is usually comfortable with an ankle tourniquet; however, intravenous sedation occasionally may be used to augment patient relaxation. The procedure may also be performed without a tourniquet. Skin incisions are marked (Fig. 7.3A).

Intermetatarsal Incision

The lateral soft tissue release is usually performed via a dorsal incision over the first web space (Fig. 7.3B). As an alternative, it may be performed through the medial approach in a transarticular release.

A 3-cm, dorsal, longitudinal incision is centered on the first intermetatarsal web space, beginning at the distal extent of the web space and extending proximally (Fig. 7.3B). The subcutaneous tissue is sharply incised, and the first and second metatarsals are distracted with a lamina spreader and a Langenbeck retractor, exposing the conjoined adductor tendon. Some surgeons detach the adductor tendon and later reattach it to the lateral capsule, while others allow it to retract. Some surgeons recommend sectioning the transverse intermetatarsal ligament. We do not routinely release the adductor tendon or intermetatarsal ligament, except when these structures are severely contracted, preventing the satisfactory correction of the HVA.

The displaced lateral sesamoid is freed up and is released from its dorsal attachments. The lateral capsule (metatarsal-sesamoid ligament) is incised longitudinally, on the superior aspect of the lateral sesamoid (Fig. 7.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree