Fig. 2.1

First page of search results from google.com.au using the terms “treatments for knee osteoarthritis”

To address the volume of potentially misleading information available to both clinicians and patients, this chapter has been compiled from guidelines released by authoritative sources and updated with a comprehensive literature search of updated information, with emphasis on the highest quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses of current evidence.

2.2 Authoritative Recommendations

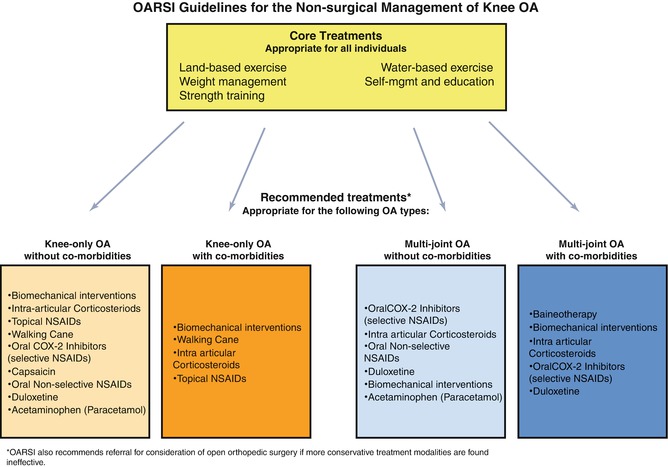

The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) recently released an evidence-based summary of recommended treatment options for knee osteoarthritis [1]. The options recommended are summarised in Fig. 2.2 and comprise a set of core treatments, suggested for the management of all types of osteoarthritis in all individuals, as well as treatment options specific to knee OA for individuals with and without serious comorbidities.

Similarly, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) has also released a 2nd edition of their clinical practice guidelines for first-line treatment of knee OA [2]. These recommendations are summarised in Table 2.1 and address a number of options not covered in the OARSI recommendations. However, the AAOS clinical practice guidelines are older (2013), and updated information has since become available for a number of recommendations.

Treatment | Recommendation | Strength | Updated information |

|---|---|---|---|

1. Self-management; strengthening; low-impact aerobic exercise; neuromuscular education; physical activity | Recommended | Strong | Yes |

2. Weight loss BMI > 25 | Suggested | Moderate | No change |

3. (a) Acupuncture | Unable to recommend | Inconclusive | None available |

(b) Physical agents (electrotherapy) | Unable to recommend | Inconclusive | No change |

(c) Manual therapy | Unable to recommend | Inconclusive | Yes |

4. Valgus-directing knee brace | Unable to recommend | Inconclusive | Yes |

5. Lateral wedge insoles | Unable to recommend | Moderate | Yes |

6. Glucosamine or chondroitin | Cannot be recommend | Strong | Yes |

7. (a) NSAIDS or tramadol | Recommended | Strong | No change |

(b) Acetaminophen | Unable to recommend | Inconclusive | Yes |

8. Intra-articular corticosteroids | Unable to recommend | Inconclusive | Yes |

9. Hyaluronic Acid | Cannot recommend | Strong | Yes |

2.2.1 Core Treatments

2.2.1.1 Exercise

Exercise is any targeted, prescribed or organised activity where participation occurs with the aim of improving strength, endurance, range of motion or aerobic capacity [1]. Exercise to treat knee OA can be based on land or in water, and reductions in pain and improvements in function are well established. The OARSI guidelines are based on a systematic review and a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, with a good overall quality of the evidence. The average size of the effect for land-based exercise on pain reduction ranges from small to moderate. Similarly, water-based exercise also provides beneficial effects on pain and function, although the expected size of the effect has yet to be established. A more recent systematic review [3] of high-quality evidence reported that land-based exercise provided a moderate short-term (up to 6 months post-treatment) reduction in pain and improved physical function.

2.2.1.2 Strength Training

Exercise that specifically targets the ability of muscles to generate force, known as strength training, has been singled out in the OARSI recommendations as a key modality to reduce pain and improve physical function for knee OA. In particular, targeting the quadriceps and other lower-limb muscle groups should be considered as a key treatment option. Strength training can take a variety of forms, but recent evidence has been based on exercises conducted on land in group or individual sessions, and training combined with mobilisation is considered most effective.

2.2.1.3 Weight Loss

Being overweight or obese is a significant risk factor for knee osteoarthritis in older adults [4, 5]. Weight loss is particularly important for individuals diagnosed with knee OA who are also considered overweight or obese. Although a programme involving diet modification with exercise is considered most effective, a moderate reduction in weight (5 % of bodyweight) over a 20-week period provides small to moderate reductions in pain and improves physical function [1]. These recommendations are based on good-quality evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. A more recent systematic review [6] suggests that weight reduction with combined diet modification and exercise is effective for pain relief and functional improvements even in elderly individuals (70 + years). Involvement of a dietitian and/or an exercise physiologist may be helpful in achieving these goals.

2.2.1.4 Self-Management and Education Programmes

Self-management programmes are distinct from patient education as they encourage people diagnosed with chronic disease to actively participate in the treatment of their condition [7]. The OARSI guidelines [1] suggest that self-management and education programmes can provide a small amount of pain reduction based on good-quality evidence stemming from a systematic review and a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. However, a more recent systematic review [7] found that the available evidence was of low to moderate quality but confirmed that such programmes provide no or small benefits up to 21 months after treatment. Importantly, this review reported that self-management programmes do not compare favourably to attention control methods or usual care.

2.2.1.5 Biomechanical Interventions

Treatment of knee OA should focus on the mechanical behaviour of the affected knee at any stage of disease progression but particularly at initial diagnosis in those with early signs [8]. Interventions designed to adjust knee and lower-limb loading during locomotion vary considerably. However, the OARSI guidelines focus on foot orthoses or shoe inserts or valgus knee braces. Foot orthoses alter the mechanical alignment of the lower leg by enhancing the valgus correction of the calcaneus, while braces apply an opposing valgus force to attenuate load on the medial knee compartment [9]. The proposed benefits of these interventions include pain reduction, reduced analgesic dosage, improved physical function, stiffness and potentially slowing disease progression. A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis [10] of valgus bracing reported a moderate to high effect on the knee adduction moment, which has been associated with disease progression [11], although the quality of current evidence remains fair.

2.2.2 Treatments Specifically for Knee Osteoarthritis

2.2.2.1 Intra-articular Injection of Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids mimic naturally occurring hormones that are anti-inflammatory in function. Common agents used to treat knee OA include betamethasone, methylprednisolone and triamcinolone which are injected directly into the joint space. The expected benefits of these injections are short-term pain relief, improved physical function and reduced joint inflammation. The current OARSI guidelines [1] suggest that corticosteroids are effective in providing short-term pain relief but are likely not appropriate for longer-term pain management. A more recent systematic review using network meta-analysis confirmed the effectiveness of corticosteroids in pain relief but reported a lack of effectiveness for improving joint function and stiffness. An earlier systematic review reported that the clinical response to injection may vary and can be predicted based on demographic and clinical factors [12].

2.2.2.2 Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

These medications have an anti-inflammatory effect and can be applied topically on the affected joint or taken orally. Oral NSAIDs are separated into Cox-2 inhibitors or non-selective options, and there is a risk of adverse events with extended use, despite moderate effects on pain. Cox-2 medications are felt to have a safer side effect profile than non-selective medications. Although the overall effect size of topical NSAIDs remains unknown, they are considered safer and better tolerated than oral NSAIDs. While oral NSAIDs are usually quite effective in pain management, their potential side effect profile makes them more suited to occasional rather than regular use, and caution should be employed in patients with any history of peptic ulceration and renal disease in particular.

2.2.2.3 Capsaicin

Capsaicin is a capsicum extract with anti-inflammatory properties which is applied topically. Although it has potential to reduce joint inflammation, reduce pain and increase function, based on good-quality evidence (systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials), its effects range from small to moderate for reducing pain and improving function compared to placebo.

2.2.2.4 Duloxetine

Duloxetine is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and is usually prescribed as an anti-depressant. Although there is fair evidence available based on systematic reviews and randomised trials, the size of its effect on knee pain remains unavailable; however, it has been reported to significantly decrease pain and improve physical function in knee OA.

2.2.2.5 Acetaminophen

Also known as paracetamol, this is commonly prescribed for a wide spectrum of pain, including knee OA. Good-quality evidence suggests that it has a small to moderate effect for pain and function, while a more recent review [12] suggests that its effects are small for pain relief. This is a medication than can be used regularly due to the relatively safe side effect profile and is probably more effective if used regularly.

2.3 Additional Treatment Options

2.3.1 Psychological Therapies

An individual’s mental health is associated with the severity of their knee OA pain and risk of pain flares [13], with depression in particular associated with self-reported pain levels [14]. Psychological therapies have demonstrated efficacy in reducing pain, disability, depression and anxiety. Cognitive behavioural therapy is the most common approach reported in the literature and is typically delivered either in-person in group or individual sessions or via the Internet. Recent systematic reviews of low-quality evidence have reported small to moderate effects on pain using traditional therapy methods [15] or by Internet delivery [16] in adults experiencing chronic pain for reasons other than headache but not specific to knee OA. However, there is potential in the future for psychological therapies to provide some benefit to individuals experiencing pain related to knee OA with little risk of adverse side effects.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree