Chapter 7. Non-verbal communication

the currency of wellbeing

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Introduction97

How do we use our body in its relationship or proximity to another person (or persons)?102

How do we use physical contact in our communications with another person?103

What importance do we attach to eye contact in our interactions?105

What importance should we attach to facial expression?106

How do we use gesture in the communication of information?107

Of what relevance is body posture in non-verbal communications?109

What is conveyed through voice – aside from words?110

Of what significance is metaphor in communication?112

INTRODUCTION

Non-verbal communication is one of those things which is so implicitly understood by every single one of us, almost from birth onwards, that we rarely give it a thought. Throughout life we abide slavishly by the cultural rules and conventions which we imbibe along with our mother’s milk, and we are not usually awakened to its structures and mechanisms until we are presented with a communication problem – our own or that of another. By way of illustration, we might think of the child, who has learned to speak and use a conventional language generally by the age of 3 years. The language has in a sense grown with him; he has had no lessons, been taught no rules, he knows nothing of grammar and syntax. He communicates ably without even thinking about it. But ask him how he arrived at that place of competent communication; ask him to describe the mechanisms with which he imparts information satisfactorily to another or receives information from another; ask him to teach his skills to a person less able, and he won’t have a clue. This is how most of us are with the matter of non-verbal language, well into adult life. But give us a communication problem of some sort, and we are forced into a position where we must acknowledge its existence and learn its workings. Dementia gives us just such a problem.

We know only too well that the advance of a dementia inexorably disrupts and may destroy verbal language and speech over the course of time. But we live in a culture and a time in which articulate facility with the written and spoken word is highly prized. Take that away from us, and most of us are like a fish out of water – removed from that natural and familiar environment in which we can live and move freely. Most of us, dare we acknowledge it, are afraid, at least initially, when we are first confronted by someone who can no longer respond to our verbal overtures in ways we have come to expect from past experience. If we are not afraid, we are at least discomfited, for such a situation diminishes our competence, renders us vulnerable, threatens our control, and, perhaps most worrying of all, has a powerful potential to make us look a fool. We have all been there. It usually happens when there is an audience – of our colleagues, our friends or uncomprehending passers-by. The person with dementia confronts us, full of emotion and intent, with a stream of jumbled incoherence to which we are clearly expected to make a response. What kind of response do we give which will satisfy the challenger, extricate ourselves from the situation, and save face at the same time? We are only too uncomfortably aware that conventional language is usually redundant at such a time, but this is precisely where our supplementary, non-verbal mechanisms of communication come into their own. If we have not recognised them before, we need to recognise them now; if we have not learned their concepts and constructs before, we need to learn them now. This is all we have left, and if we do not assimilate the subtleties and intricacies of this language, we might as well forget about planned therapeutic interventions. For this is the currency with which we trade, and nobody is going to ‘buy’ our therapeutic interventions unless they are presented in a language which is understood.

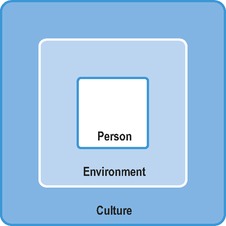

Non-verbal communication is perhaps best understood as operating in an interplay of culture, environment and person. We might think of it as in Figure 7.1. It is commonly assumed that human beings are the sole transmitters of information and messages, and without doubt we have an immense potential in this area.

‘There seems to be no agent more effective than another person in bringing the world for oneself alive, or, by a glance, a gesture, or a remark, shrivelling up the reality in which one is lodged.’ (Goffman 1961)

However, messages are also powerfully carried by the environment and the culture around us.

‘The physical environment unremittingly offers us possibilities of experience, or curtails them. The fundamental human significance of architecture stems from this. The glory of Athens … and the horror of so many features of the modern megalopolis is that the former enhances and the latter constricts man’s consciousness.’ (Laing 1967)

Imagine then the impact of some long-stay environments on the consciousness and wellbeing of people who have dementia; people who, arguably, are more tuned in to non-verbal messages than verbal.

What is the message being conveyed by the environment described in Box 7.1? Well, surely something like – ‘You are not worth much. You will die soon anyway. The sooner the better’. Clearly, it does not need a person to come and say to the inhabitants of that ward – ‘You are not worth visiting/spending money on/being clean for.’ The physical environment says it all. And the message of the physical environment is supported in turn by a message from the prevailing socioeconomic culture which has determined that the ward will close. And this message says that we must move with the times, live more cost-effectively, save money – buildings and services take priority over people.

Box 7.1

On the ward that I work on now, there is a huge black unspoken ‘non-verbal’ looming above us all. The ward is closing; it will not be replaced; the beds will be absorbed by two other wards on the opposite side of town. The ward is scruffy and smelly. Paint is flaking off the ceiling. The silk flowers have stood on the windowsill for so long they have been bleached a dirty yellow by the sun. The tear in the curtain has never been mended. Relatives’ visits are rare; consultant visits rarer. The incidence of falls has gone up, which is strange because there is a pall of lethargy over the place which makes you feel as though nothing ever happens here. Actually, not much does beyond the conventional routine of nursing care.

Nevertheless we must not lose sight of the fact that it is people who shape both environment and culture; environment and culture can only pass on the message that we as individuals or as a society permit. The person is at the core.

So how are messages reciprocated in a non-verbal manner? How does it all work? How can we ensure that channels of communion between ourselves and the people with whom we work are, and remain, open and uncluttered?

The greater part of this chapter is concerned with an exploration of the way we use and interpret body and voice, but effective communications are not just reliant upon a knowledge and use of this or that movement or gesture or voice tone. These are important – hence we will concentrate upon them. But we must first say that the essence, the essential element of effective communications is actually a matter of integrity – what we believe must match what we say (verbally) which must match what we do with our body and voice. Any discrepancy will engender a mixed message, and mixed messages serve only to confuse and threaten. Mixed messages are clogged channels. I have a poignant cartoon which I cut out of a social work journal several years ago. Two elderly ladies are sitting together in a living room chatting over a cup of tea. One is saying to the other, ‘My social worker is very interested in gardening – she always looks out of the window when I’m talking to her’. This is not integrity – it is dishonesty. It is a mismatch of what the social worker believes, says and does. And we who look upon this scene know that the elderly lady also knows that – maybe only at a subliminal level, but she knows it. The message she has received is, ‘Your garden is more important to me than you are’. Or possibly even, ‘You are of so little value to me that I would rather look at anything but you’. Powerful messages – which close down the channels of communion.

Look again at the illustration of Julie and Audrey in Box 4.4– not a dissimilar scenario to the cartoon described above. Communion was established first and foremost because Julie really liked Audrey, because she believed that Audrey was a fellow human being worthy of attention and consideration, and because what she did matched what she felt.

Box 7.4

There was something different about Betty today. She was wearing a beautiful white lacy cardigan – clean and fresh. She looked really lovely. So I took her hand and told her so. ‘Do I? Oh, thank you’, she said and smiled. Just a few minutes later, I happened to notice her pass Molly in the corridor. She paused in front of Molly, stroked her cheek softly and lovingly, and said, ‘You look lovely’. Molly too smiled, glowed rather gently, and moved on.

In the case described in Box 7.2, neither Amy nor I ever had to put any of our initial antipathy into words, but we both knew exactly how the other felt. We knew it because of that mismatch of inner attitudes, word and actions; and that mismatch effectively blocked the channels of any real communion between us for some considerable time.

Box 7.2

When I first came to work on Ward 10, the biggest problem I had was a lady called Amy. Amy was very confident, upper class, verbose. She always seemed to have the upper hand with me and she frightened me. I got on her nerves with my polite ‘therapist’ approach, and I’m pretty sure she viewed me as a female rival in the group; she held power in the ward society, and so did I, though of a quite different nature. Often she would call me a hussy or such like, and responded to all my endeavours in a resistive fashion. If asked to join in, she’d opt out; if asked to opt out she’d join in. It was difficult for me to express my anger, frustration and irritation with her, or the sense of failure she provoked in me. Therapists aren’t allowed to give vent to these feelings, and so we got off to a bad start because I couldn’t be authentic and honest with her. She knew this and mistrusted me. Ultimately, it was a soft cuddly toy that came to our rescue – two in fact. Amy had a long-standing relationship with two big white fluffy cats – her ‘boys’ she called them; and they went everywhere with her, one under each arm. Often, they were my only real point of contact with her; I made as much of them as I could, and they gradually came to act as a bridge between us. Slowly, she came to trust my regard for them, and appreciate my capacity to enjoy them with her. The day she asked me to look after them for a few minutes was a big day for me; it meant we had truly achieved an authentic relationship of mutual regard.

What of the person with dementia? Does cognitive incapacity impinge upon a person’s ability to understand and use non-verbal means of communication? It seems not. It seems that as far as we can tell, a person with dementia is just as able (if not more so) to understand and assimilate non-verbal communications as an unimpaired person. In a piece of empirical research that must surely be ahead of its time, Hoffman et al (1985) demonstrated that:

▪ non-verbal communication abilities of people with dementia are comparable to those of unimpaired people

▪ even people with severe dementia are responsive to emotional undertones in the environment

▪ positive affective non-verbal messages elicit positive verbal and non-verbal responses in people with dementia

▪ negative affective non-verbal messages elicit withdrawal and apparent discomfort

▪ social conventions are apparent even in people with severe dementia.

Hoffman et al conclude that ‘even persons who have completely lost language capabilities are still as responsive to non-verbal communications as the non-demented’. They also go as far as to suggest that the cognitive losses of dementia may actually serve to sharpen non-verbal communication abilities, rather as a loss of visual acuity sharpens the remaining senses to a keener sensitivity. A more recent study (Hubbard et al 2002) supports Hoffman’s findings.

These are critically important observations, which leave us with no excuses for not becoming diligent students of this supplementary language. They offer a challenge to the careless practice of those who attribute little or no understanding to people with dementia, and a powerful incentive to make the best possible use of that which remains.

So where do we start? Let’s go back to our first analogy of the child imbibing his first knowledge of the language. He may of course never get beyond that, nor wish to do so. He may speak the language perfectly well, and yet never learn how to spell, or recognise the different parts of speech, or know how to parse sentences. But if he should be going on in later life to become a linguist or an author or a teacher, he will certainly need to acquire a deeper understanding of the structure of language; indeed he will probably be well motivated to dig deeper. The starting point for this child is usually a book of English usage and a good teacher. And here our analogy falls down rather, for our non-verbal language is not taught in school in the conventional manner of other languages; it is not on the national curriculum; you can’t take an A-Level in it.

Nevertheless, much is known and has been discovered about non-verbal communication over the years, and we are about to turn our attention to this. But the key to learning any language is something we don’t have to go searching the schools and bookshops for; the key is in listening to others, listening and establishing individual and cultural patterns in what we hear. It is also in listening to ourselves and shaping our own communications to match those we are receiving from the other person. With verbal language we listen; with non-verbal language we watch; there isn’t a great deal of difference, it’s a tuning in. What we are saying here really is that the art of learning the language of non-verbal communication, is in becoming a skilled observer of others, and an honest critic of ourselves. Two questions must always be at the forefront of our minds in dementia care: what message is this person trying to deliver to me, and what message am I giving (or trying to give) to this person?

What we attempt to deal with in this chapter, is to highlight those non-verbal mechanisms with which we all communicate information, and to draw attention to their use and misuse in dementia care. Non-verbal mechanisms of communication rely on the use of body and voice. We will deal with the body first.

HOW DO WE USE OUR BODY IN ITS RELATIONSHIP OR PROXIMITY TO ANOTHER PERSON (OR PERSONS)?

It is well known that each of us carries around about us a set of invisible social barriers, rather like a series of concentric circles, which determine who gets close to us and who doesn’t. The actual permitted distances vary from culture to culture, but in western society generally, we tend to deal in fairly extended distances. In professional/client contact, we need to keep anything from four to twelve feet between us for comfort. In informal interactions between friends, this distance is something between eighteen inches and four feet; and only intimates are permitted within the eighteen inch circumference (Hall 1966). The inappropriate person who invades those set barriers causes us grave discomfort, for what they have done is to violate a socially acceptable norm. Our response is immediate withdrawal. I once found myself backed right across my kitchen and up against the sink unit by a boiler repair man who was consistently invading my own personal 18 inches of intimate space. Not only was I in considerable discomfort, but I was also very confused. My first thought, that this might be a sexual overture, I discarded; for even when drawn to full height he was still a foot shorter than I and his verbal communications were in no way sexually loaded. Ultimately (when I had extricated myself) I concluded that either he had never learned social graces, or he had been brought up in a different cultural setting. But the clear mismatch between what he was saying (entirely acceptable) and what he was doing (entirely unacceptable) was very confusing, and I never did decide what the message was that I was supposed to have received.

The situation described in Box 7.3 was, I believe, an issue of Keith’s personal space and my invasion of it. Keith and I have a good relationship; most of the time I would describe it as a relationship between friends which, according to the research indicated above, would allow a comfortable distance of between two and four feet. This does indeed describe how we normally behave with each other. As his carer though, I sometimes have to invade that 18 inches of intimate space, for example, at home when he needs assistance with dressing. On these occasions he tolerates such invasions usually with equanimity, intuitively understanding that in such situations the conventional rules are suspended. This time I was again attempting to respond as carer, but the circumstances were different. I had again invaded intimate space, but this time the action was unsolicited, in a public place where people might be looking, and at a time when he was clearly feeling more vulnerable than usual. It caused him immediate and obvious discomfort, and caused me to think again. As soon as I restored the distance balance to the three or four feet afforded by the coffee table, it gave him the (literal) space he needed re-assert normal proceedings.

Box 7.3

Keith and I had gone down to the Leisure Centre to play squash. We had been playing energetically for 20 minutes or so when suddenly Keith came over faint and wobbly. I thought he was going to fall and managed to get him safely to the floor. I wasn’t sure what this was but after a short while he seemed recovered, though he was confused and embarrassed and shrugged off an offer of help from one of the attendants. It was a short walk to the nearest chair in the coffee bar, and as he was swaying and still wobbly I felt I needed to hang on to him in case he should stumble or fall. So I did the thing that felt most natural for me and which I thought would draw the least attention – I held his hand. Unusually in such circumstances there was no responding pressure – it was like holding a dead hand. And the hand was rapidly withdrawn just as soon as a chair was safely in sight. I realised that with the best of intentions I had overstepped the mark and invaded Keith’s sense of personal space.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree