Nocardiosis

Jeffrey R. Starke

Nocardiosis is a localized or disseminated infection caused by an aerobic actinomycete. It was described first in humans in 1890, 2 years after an aerobic actinomycete was observed in bovine farcy, an emaciating disease of cattle that causes pulmonary lesions and cutaneous abscesses. In humans, the soil-borne agent usually causes a pulmonary lesion that may be clinically silent or may provoke chronic bronchopulmonary disease. Hematogenous dissemination from the lungs may infect the central nervous system (CNS), bones, liver, spleen, or other soft tissues. Reports suggest an increasing incidence or recognition of primary lymphocutaneous forms of nocardiosis in children, usually involving the face or an extremity.

Most reported cases of nocardiosis have occurred in immunocompromised hosts, especially in patients with hematologic malignancy or in those being treated with immunosuppressive drugs, with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, with chronic granulomatous disease, or with chronic underlying pulmonary disease. Only the lymphocutaneous form of nocardiosis occurs commonly in immunocompetent patients.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Nocardia are distributed widely in nature. Their natural habitat is soil and decaying vegetable matter. Infection in humans occurs by inhalation or by direct skin inoculation of soil or organic particles. Because these organisms rarely are part of the normal flora of humans and are not a common laboratory contaminant, their isolation from a clinical specimen suggests disease.

Some studies support the concept that Nocardia can be respiratory saprophytes. No definite evidence for animal-to-person or person-to-person transmission exists, although one cluster of cases has suggested the latter possibility. Tick bites and animal scratches have been proposed as the causes of several cases of cutaneous nocardiosis. Traumatic introduction of Nocardia into tissues has caused endophthalmitis, poststernotomy mediastinitis, and mycetoma lesions. Nosocomial cases have been described; they include an outbreak of nocardiosis in renal transplant patients that was related to organisms in the dust and air of the hospital unit.

Between 500 and 1,000 recognized cases of nocardiosis, of which 85% are serious pulmonary or systemic infections, occur in the United States each year. Cases occur in a random geographic distribution, with no seasonal or occupational predilection. Affected men outnumber women by three to one. Although persons of any age can develop nocardiosis, most patients are between 21 and 50 years of age.

ETIOLOGIC AGENTS

Before 1943, cases of nocardiosis were included under the term actinomycosis. Waksman and Henrici separated the pathogenic Actinomycetaceae into two groups: The microaerophilic and anaerobic actinomycetes were placed in the genus Actinomyces, and aerobic forms were assigned to Nocardia. Current classification places the aerobic actinomycetes in a separate family, Nocardiaceae.

Nocardia reproduce by fragmentation into bacillary and coccoid elements, but they are differentiated by their propensity for filamentous growth with true branching. The organisms grow over a wide range of temperatures on simple laboratory media, such as blood agar. Colonies on agar may be smooth and moist or rough. Their color varies from cream to brick red. Nocardia may grow poorly on antibiotic-containing media used for isolation of fungi. Colonies in pure culture often grow after 48 hours of incubation, but growth can take up to several weeks in mixed cultures from clinical material.

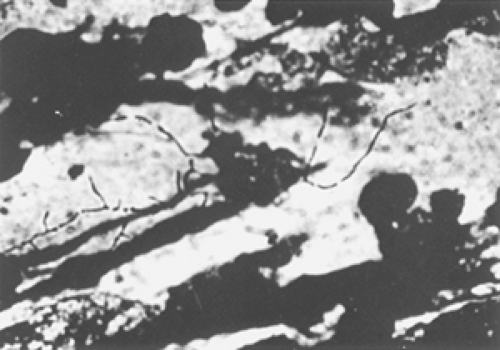

The usual microscopical appearance of Nocardia is a delicate, weakly gram-positive, beaded branching filament (Fig. 152.1). Most Nocardia are acid-fast but retain fuchsin less avidly than do mycobacteria. Acid and alcohol solutions (i.e., Ziehl-Neelsen stain) decolorize Nocardia, but more basic solutions do not. A modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain using 1% sulfuric acid is the best solution to demonstrate Nocardia in clinical specimens.

Nocardia asteroides is the predominant pathogen, involved in as many as 90% of human nocardiosis cases. N. brasiliensis now is recognized as a common cause of lymphocutaneous nocardiosis in immunocompetent patients and as the major cause of mycetoma in Central and South America. In experimental animals, N. brasiliensis is more virulent than are other Nocardia species. The association of skin trauma with lymphocutaneous nocardiosis suggests that, once beyond the skin barrier, N. brasiliensis can cause local disease despite normal host defenses. Other species, including N. otitidiscaviarum (caviae), N. nova, N. farcinica, and N. transvalensis, rarely are involved in human disease.

FIGURE 152.1. Microscopical appearance of Nocardia brasiliensis. Beaded, branching filaments are visible in pus from a cutaneous abscess.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|