Abstract

Background

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is one of the complications of atherosclerosis. Intermittent claudication is the second stage of PAD. In controlled studies on patients with Stage II PAD, intensive rehabilitation training has proved effective for improving the walking distance in this population. The objective of this prospective study was to determine the effects of treadmill interval training followed by active recovery (low-intensity exercise).

Methods and results

Eleven patients with Stage II peripheral arterial disease were included in a rehabilitation program (mean age 68.3 ± 10.3 years) for five days a week during two weeks including global exercises, exercises below and above the level of injury. The interval training program consisted of treadmill training for 30 minutes twice a day (morning and evening) with a progressively increased intensity: the first week speed was increased and the second week slope was increased. Each session included five six-minute cycles. Each cycle was made of three minutes of active workout followed by three minutes of active recovery.

Results

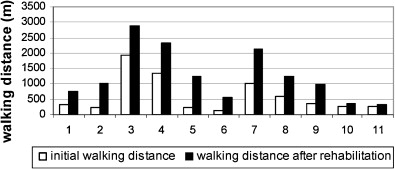

All patients improved their walking distance, from a mean of 610 m (120–1930) at the beginning of the program to a mean of 1252 m (320–2870) at the end ( P = 0.003). All patients were very motivated by the rehabilitation training program No adverse event was reported.

Conclusion

This study showed that an interval training program with active recovery was effective and safe for patients with Stage II peripheral arterial disease, the patients’ motivation was high. This study must now be validated by a clinical trial.

Résumé

Objectif

L’artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs peut se manifester par une ischémie d’effort avec une claudication intermittente des membres inférieurs. Si l’efficacité du réentraînement à l’effort est démontrée, les modalités de ce réentraînement sont à préciser. L’objectif de cette étude pilote a été d’étudier, chez les patients présentant une ischémie d’effort, la tolérance et l’effet sur l’amélioration de la distance de marche du réentraînement sur tapis roulant fractionné avec récupération active (interval training).

Sujets et méthodes

Onze patients artériopathes en ischémie d’effort (âge moyen 68,3 ans ; de 48 à 83 ans) ont bénéficié de deux semaines de réentraînement à la marche sur tapis roulant selon un mode intensif et fractionné, avec deux séances de 30 minutes par jour d’intensité progressivement croissante : incrémentation de la vitesse la première semaine, incrémentation de la pente la deuxième semaine. Chaque séance contenait une succession de cinq cycles de six minutes. Chaque cycle était constitué de trois minutes de travail actif suivi de trois minutes de récupération active. Ce réentraînement était associée quotidiennement à des exercices sus- et sous-lésionnels et à une gymnastique globale.

Résultats

Tous les patients augmentaient leur distance de marche, qui passait en moyenne de 610 m (120–1930 m) en début de programme à 1252 m (320–2870 m) en fin du programme de rééducation ( p = 0,003). Tous s’étaient déclarés motivés par le type de programme de rééducation proposé. Aucun effet indésirable n’a été noté.

Conclusion

Le réentraînement de la marche sur un mode intensif et fractionné comprenant une récupération active est réalisable et efficace dans l’artériopathie au stade d’ischémie d’effort. Ces résultats sont à confirmer par un essai clinique.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Atherothrombotic disease (ATD) affects preferentially the lower limbs with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) but also the brain, carotids, coronaries and aortas. The prevalence of symptomatic PAD (intermittent claudication or effort ischemia Stage II of Fontaine’s classification) is between 0.8% and 1.5% in the general population and it goes up to 5% for men and 2.5% for women after the age of 60 . This severe pathology can endanger the functional and vital prognosis of the limb. The arterial injury defines the limit between the area below the level of injury (chronic ischemia) and the one above the level of injury. The primary treatment for intermittent claudication is rehabilitation training . Supervised walking training programs have a better impact than just medical walking recommendations . Schoop in 1964 then Strandness in 1969 started the first rehabilitation programs centred on treadmill walking with evaluation measures. Their positive effects have been validated . Furthermore, the benefits of a rehabilitation program on the medium-term (one to two years) appeared similar to angioplasty’s benefits . The positive impact of rehabilitation training is due to an improved metabolism (reduction in systemic inflammation markers), muscle improvements (improved mitochondrial metabolism) and improved microcirculation (increased nitric oxide improving vasodilatation, minimal increase of the flow in the collaterals) . Also, rehabilitation training triggers a better management of cardiovascular risk factors: blood pressure, diabetes and dyslipidemia control. The quality of life for patients with ATD and intermittent claudication or effort ischemia is improved by rehabilitation training .

Rehabilitation training usually combines supervised treadmill walking, muscle strengthening exercises below the level of injury in order to improve local vasodilatation and exercises above the level of injury (including cycloergometer training) to improve muscle functions. This vascular training can sometimes associate routine exercises in a swimming pool or a gym, as well as intermittent pressotherapy (short-timed applied to the root of the thigh and adjusted according to the heart rate frequency) to increase arterial vascularisation in the lower limbs. Therapeutic patient education focused on managing cardiovascular risk factors is essential.

To date, no standard type of rehabilitation training for PAD has been clearly defined . Globally two types of training have been proposed: training at constant intensity and moderate speed during a set time period and training at a higher intensity with walking exercises maintained until discomfort or the onset of claudication stopped the exercise . Submaximal interval training associated to active recovery has never been reported in patients with peripheral arterial disease. However, this type of training has been used for a long time in athletes. It is better suited to <SPAN role=presentation tabIndex=0 id=MathJax-Element-1-Frame class=MathJax style="POSITION: relative" data-mathml='V˙O2-max’>V˙O2-maxV˙O2-max

V ˙ O 2-max

improvement in healthy subjects (not used to exercising) than constant effort training . This type of rehabilitation training has been recently proposed for cardiovascular pathologies and it reported better results on the <SPAN role=presentation tabIndex=0 id=MathJax-Element-2-Frame class=MathJax style="POSITION: relative" data-mathml='V˙O2-max’>V˙O2-maxV˙O2-max

V ˙ O 2-max

than with regular training for: metabolic syndrome , after a coronary bypass , and for patients with cardiac insufficiency . Interval training seems to be more effective in terms of cardiovascular risk factors management , improved endothelial function or cardiac remodelling . The training tolerance is good even in patients with severe cardiac insufficiency . Interval training is now being recommended for cardiac rehabilitation in patients with very impaired functional abilities .

The hypothesis underlying this study was to assess the feasibility of conducting interval training with active recovery and evaluating its efficacy in patients with Stage II peripheral arterial disease.

1.2

Patients and methods

Eleven patients with stage II PAD of the lower limbs hospitalised for rehabilitation care were included in this pilot study. Exclusion criteria were: unstable coronary disease, menacing injuries of the femoral tripod and iliac axis, pathologies limiting walking abilities such as locomotor impairments on the lower limbs. The population included eight men and three women mean age of 68.3 ± 10.3 years (48 to 83 years). The majority of patients (10/11) had hypertension and dyslipidemia (8/11). Six patients were diabetic. Most patients (8/11) had no posterior tibial pulse; 5/11 had no popliteal pulse.

1.2.1

Rehabilitation program proposal

The patients benefited from a two-week rehabilitation program with therapeutic education on managing cardiovascular risk factor and workout training. This training included global gym exercises, exercises below the level of injury (for proximal lesions: sit to stand and tiptoe, for medial lesions standing on tiptoes and for distal lesions: toe flexing exercises) and above the level of injury (including cycloergometer training) and treadmill retraining.

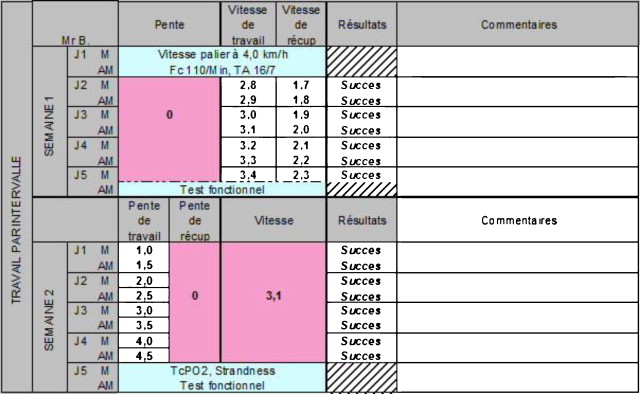

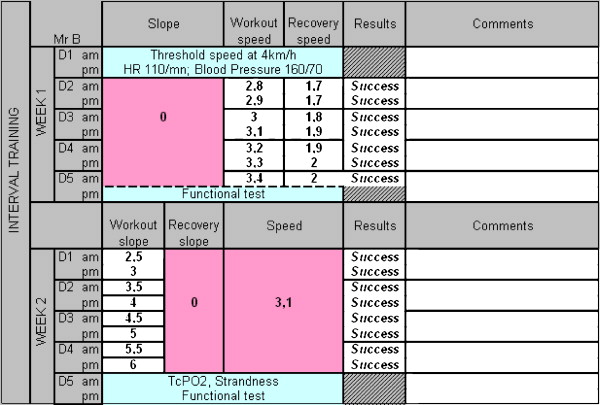

This treadmill training (Techmedphysio ® ) included two 30-minute sessions per day with increasing intensity. Each session had five six-minute cycles and each cycle was made of three minutes of active workout followed by three minutes of active recovery. Training intensity was progressively increased as such: the first day active workout’s intensity was individually adjusted by fixing the walking speed at 70% of the maximum walking speed (evaluated at D1 on the treadmill by increasing speed by 1 km/h every three minutes, maximum speed was determined when the patient reached his or her maximum tolerable pain). For the active recovery phases walking speed was set at 40% of the maximum walking speed. Speed was then increased by 0.1 km/h per session without any pain during the first week of rehabilitation training. The onset of claudication during a session would lead to decreasing the walking speed by 0.1 km/h at the next session. The second week, the desired work intensity was achieved by increasing the slope by 0.5% while running at a constant speed (mean speed values collected during the first week), and the active recovery phases took place at the same speed but with no slope. As an example, the typical program for a patient is shown in Fig. 1 .

1.2.2

Evaluation criteria

The main evaluation criterion was the difference in the walking distance before and after rehabilitation training. Walking distance is defined as the distance walked on the treadmill at 3 km/h with no slope and before the onset of maximum tolerable pain.

1.2.3

Statistical analysis

Walking distance at the beginning and end of the rehabilitation program were compared using the Wilcoxon Matched-Pairs Signed-Ranks Test DM. The statistics were computed with the SPSS software.

1.3

Results

Upon inclusion in this rehabilitation program the mean walking distance was 610 m ( r : 120–1930 m) and by the end of the program it significantly increased to 1252 m ( r : 320–2870 m). The significance is P = 0.033. Fig. 2 shows that all patients had improved by the end of the program. The results validate an excellent efficacy for interval training in atherosclerotic patients. The program’s tolerance was good since all patients were able to follow the program until the end without any reported adverse events.

1.4

Discussion

In this pilot study the rehabilitation program consisted of submaximal interval training over a two-week period with intensity increasing progressively from one session to the next followed by active recovery. This program showed its effectiveness on improving the walking distance in patients with PAD. This type of rehabilitation program is perfectly suited to subjects with atherosclerosis known to be fragile. Program compliance was excellent, the fractioned nature of the exercises prevented boredom, as is often the case with continuous walking programs .

Several studies have assessed the effects of interval training in cardiac pathologies and thus highlighted some hypotheses on the underlying mechanisms involved in the walking distance improvement showed for the population in our study . This improvement is probably due to the combined effects of improved cardiorespiratory, endothelial and muscular parameters. In cardiac pathologies studies have validated the superiority of interval training vs. continuous training . This could be explained by a better compliance to the program , patients reported that continuous training was rather boring and not very motivating; by improving skeletal muscle function , interval training would allow to reach higher workout intensity with better aerobic output while not being limited by cardiac functions .

Contrarily to the studies mentioned focusing on cardiac pathologies and metabolic syndrome we did not use the <SPAN role=presentation tabIndex=0 id=MathJax-Element-3-Frame class=MathJax style="POSITION: relative" data-mathml='V˙O2-max’>V˙O2-maxV˙O2-max

V ˙ O 2-max

to set the intensity of our program: in patients with PAD the limiting factor for walking is peripheral and not cardiac. The intensity of our training program was set according to the intensity triggering pain and not <SPAN role=presentation tabIndex=0 id=MathJax-Element-4-Frame class=MathJax style="POSITION: relative" data-mathml='V˙O2-max’>V˙O2-maxV˙O2-max

V ˙ O 2-max

.

Our study was an observational pilot study conducted on a small number of subjects. Even if the results are clear and clinically significant since the patients doubled their walking distance after two weeks, they must be validated by a clinical trial comparing the efficacy of interval training vs continuous training. Other evaluations such as respiratory and cardiac functions, <SPAN role=presentation tabIndex=0 id=MathJax-Element-5-Frame class=MathJax style="POSITION: relative" data-mathml='V˙O2-max’>V˙O2-maxV˙O2-max

V ˙ O 2-max

and muscle metabolism would be interesting to explain the underlying mechanisms involved in functional improvement in atherosclerotic patients with Stage II PAD.

1.5

Conclusion

This pilot study shows that it is possible to propose a two-week interval training program with active recovery on the treadmill to patients with Stage II PAD and that this type of program does considerably increase their walking distance. These results must be validated by a clinical trial.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs (AOMI) est une des localisations préférentielles de la maladie athérothrombotique avec les localisations cérébrales, carotidiennes, coronariennes et aortiques. La prévalence de l’AOMI symptomatique (claudication artérielle intermittente ou une ischémie d’effort stade II de Leriche et Fontaine) est de 0,8 à 1,5 % dans la population générale et, chez les sujets de plus de 60 ans, de 5 % pour les hommes et 2,5 % pour les femmes . C’est une pathologie grave, pouvant engager le pronostic fonctionnel et vital du membre. Le niveau de la lésion artérielle définit la limite entre le territoire sous-lésionnel (en ischémie chronique) et sus-lésionnel.

Le traitement de première intention de l’ischémie d’effort ou claudication artérielle intermittente est actuellement la rééducation . Un entraînement à la marche supervisé est considéré supérieur à un encouragement à marcher . Schoop en 1964 puis Strandness en 1969 ont débuté les premiers programs centrés sur la marche avec évaluation par test sur tapis roulant. Leur efficacité a été bien démontrée . À moyen terme (un à deux ans), le bénéfice d’une rééducation serait même similaire à celui de l’angioplastie .

L’effet bénéfique de la rééducation est dû aux effets métaboliques (diminution des marqueurs systémiques de l’inflammation), musculaires (amélioration du métabolisme mitochondrial) et microcirculatoires (augmentation de l’oxyde nitrique influençant la vasodilatation, augmentation minime du débit dans les collatérales) , ainsi qu’à la maîtrise des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaires : meilleur contrôle du profil tensionnel, de l’équilibre diabétique et lipidique . La qualité de vie des patients présentant une ischémie d’effort est améliorée par la rééducation .

La rééducation associe généralement un réentraînement à la marche supervisé sur tapis roulant, des exercices de renforcement musculaire dans le territoire sous-lésionnel pour créer un appel circulatoire favorisant une vasodilatation régionale, et des exercices dans le territoire sus-lésionnel (dont exercices sur cycloergomètres à bras) pour améliorer le rendement musculaire. Cette rééducation vasculaire associe aussi parfois des exercices généraux en piscine ou au gymnase, ainsi que de la pressothérapie intermittente (brève appliquée en racine de cuisse réglée selon la fréquence cardiaque) pour augmenter la vascularisation artérielle distale. Une éducation thérapeutique avec prise en charge des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaires est indispensable.

Le type de réentraînement à la marche pour rééducation de l’artériopathe reste mal précisé . Schématiquement deux types sont proposés. L’entraînement peut se faire à intensité constante et vitesse modérée pendant une durée déterminée . Il peut être à intensité plus élevée avec des phases de marche jusqu’à l’apparition d’une gêne voire d’une claudication imposant l’arrêt . Un réentraînement sur un mode fractionné associant une période de travail sous-maximal et une période de récupération active n’a jamais été rapporté chez l’artériopathe. Cette technique d’entraînement est utilisée depuis longtemps chez les sportifs. Elle améliore plus efficacement la <SPAN role=presentation tabIndex=0 id=MathJax-Element-6-Frame class=MathJax style="POSITION: relative" data-mathml='V˙O2-max’>V˙O2-maxV˙O2-max

V ˙ O 2-max

de sujets sains non sportifs qu’un entraînement à effort constant . Elle a été récemment proposée en rééducation des pathologies cardiovasculaires avec un meilleur résultat sur la <SPAN role=presentation tabIndex=0 id=MathJax-Element-7-Frame class=MathJax style="POSITION: relative" data-mathml='V˙O2-max’>V˙O2-maxV˙O2-max

V ˙ O 2-max

que celui obtenu par un entraînement à effort constant pour le syndrome métabolique dans les suites d’un pontage coronarien , et pour l’insuffisance cardiaque . L’entraînement fractionné serait également plus efficace en termes de contrôle des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaires , d’amélioration de la fonction endothéliale ou de remodelage cardiaque . La tolérance est bonne, même chez des sujets ayant une fonction cardiaque très altérée . Cette rééducation en mode fractionné est désormais recommandée lors de la rééducation cardiaque chez des sujets ayant des capacités fonctionnelles très diminuées .Notre hypothèse de travail était que le réentraînement fractionné avec récupération active était faisable et efficace chez les artériopathes en ischémie d’effort.

2.2

Sujets et méthodes

2.2.1

Sujets

Onze patients atteints d’artériopathie oblitérante des membres inférieurs au stade d’ischémie d’effort, de stade II de Leriche et Fontaine, et hospitalisés pour rééducation, ont été recrutés pour cette étude pilote. Les critères de non-inclusion étaient : coronaropathie instable, lésions menaçantes du trépied fémoral et de l’axe iliaque, pathologies limitant la possibilité de marche telle une pathologie de l’appareil locomoteur localisée aux membres inférieurs. Il s’agissait de huit hommes et trois femmes âgés de 68,3 ± 10,3 ans (48 à 83 ans). Presque tous (10/11) étaient hypertendus et dyslipidémiques (8/11). Six étaient diabétiques. La majorité (8/11) n’avait pas de pouls tibial postérieur ; cinq patients sur 11 n’avait pas de pouls poplité.

2.2.2

Programme de rééducation proposé

Les sujets bénéficiaient d’un programme de rééducation de deux semaines comportant une éducation à la maitrise des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire et une rééducation. La rééducation comportait une gymnastique globale, des exercices sous-lésionnels (pour les lésions proximales exercices de type assis-lever-pointe, pour les lésions médiales pointe des pieds, pour les lésions distales exercices des griffes d’orteils) et sus-lésionnels (dont cycloergomètre à bras), et un réentraînement à la marche sur tapis roulant.

Le réentraînement sur tapis roulant (Techmedphysio ® ) comportait deux séances de 30 minutes par jour dont l’intensité était progressivement croissante : incrémentation de la vitesse la première semaine, incrémentation de la pente la deuxième semaine. Chaque séance contenait une succession de cinq cycles de six minutes. Chaque cycle était constitué de trois minutes de travail actif suivies de trois minutes de récupération active. L’intensité du réentraînement était incrémentée de la façon suivante. Le premier jour l’intensité des phases de travail actif était ajustée individuellement en fixant la vitesse de marche à 70 % de la vitesse maximale de marche (évaluée à j1 sur tapis roulant en augmentant la vitesse de 1 km/h par paliers de trois minutes, la vitesse maximale étant la vitesse atteinte lors de l’apparition de la douleur maximale tolérable). Pour les phases de récupération, la vitesse de marche était fixée à 40 % de la vitesse maximale de marche. La vitesse était ensuite augmentée de 0,1 km/h à chaque séance effectuée sans douleur durant la première semaine de rééducation. La survenue d’une claudication lors d’une séance entraînait une diminution de 0,1 km/h de la vitesse de marche de la séance suivante. La deuxième semaine l’intensité, de travail était modulée par un incrément de pente de 0,5 % à vitesse constante (moyenne des vitesses de la première semaine), et les phases de récupération actives se faisaient à même vitesse à pente nulle. À titre d’exemple, le programme suivi pour un patient est représenté en Fig. 1 .