12 Neuromusculoskeletal disorders

It is through an integrated approach that acute dysfunction of the musculoskeletal system is best treated, ensuring that causative factors are identified and where possible eliminated, and that reflex soft tissue adaptation is corrected, providing total relief of symptoms and preventing recurrence. It should also be recognised that this scenario may occur in reverse, whereby soft tissue problems arising from excess muscle tension can produce postural change and muscle imbalance, thus precipitating joint problems (Marks 1993).

The musculoskeletal system

They are dealt with as mechanical and postural (including occupational factors, discussed in more detail in Chapter 14); disease; and trauma and surgical factors.

Mechanical and postural factors

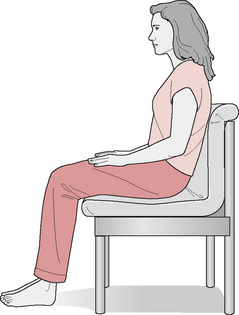

The postural changes may be as a result of habit, for instance many hours over several years spent slumped in easy chairs, or sitting with rounded shoulders and a poking chin at a keyboard until, gradually, less muscular effort is made to maintain an upright posture against gravity (Figs. 12.1, 12.2). The postural (antigravity) muscles have a tendency to shorten (Janda 1983) and become structurally tight, and their antagonists tend to become reflexly inhibited and weakened. This produces postural changes and instability. A typical pattern is one of weakened, lengthened abdominal muscles and weak glutei. The hip flexors and the back extensors become short and tight. This was identified by Janda as the ‘crossed pattern’; it is accompanied by tight hamstring muscles, thought to be an attempt to stabilise the pelvis. The situation becomes more complicated where there are many short muscles together. The erector spinae, for example, although seen as one muscle mass running along either side of the spinal column, consists of three groups of muscles (iliocostalis, longissimus and spinalis), each of which has a subgroup in each area of the spine. The fibres of erector spinae run in several different directions over different distances. It is important that these muscles act in coordination, but imbalance can occur within the group. According to Janda, antagonist muscles tend to react in a way that is opposite to their agonist, either weakening or shortening, resulting in a muscular imbalance around a joint and eventually throughout the body.

The muscles adapt to their shortening, probably losing sarcomeres (Williams & Goldspink 1978), and their connective tissue loses length and flexibility. As the reflex weakening of the antagonist occurs, these postural changes become self-perpetuating. They can be exacerbated, or indeed caused, by body language, whereby tall people may develop rounded shoulders, shy people a protective flexed posture in which the pectoral muscles become tight and the thoracic spine flexed and stiff, the chronically depressed a poking chin in which the extensor muscles of the neck become short (for further discussion see Kurtz & Prestera 1984). The normal mechanical stresses which the tissues experience through everyday functional activities are correspondingly altered and may be magnified as some (spinal) joints may now be held at an extreme of their range. The increased stress on the connective tissue causes remodelling and the fibres become laid down along the new lines of stress, so they actually change structure to accommodate the postures. Usual patterns of movement may start to strain this altered tissue. For example, sporting activities, or sudden explosive movements, such as running for a bus which places dynamic stretch on tissue, may strain or partially tear connective tissue. Adhesions or excess fibrous tissue may be laid down in response and attempts to correct the posture to a ‘normal’ one, or attempts at exercising to strengthen weakened antagonists, will produce pain. This is because ‘normal’ stress which protects joints has now become ‘abnormal’ as far as the collagenous tissues are concerned. Applying normal stress will in fact weaken the tissues as the fibres now lie in the direction of the abnormal stress and are therefore ill-equipped to resist normal stress. The obvious result of these attempts to correct the situation will be pain. This scenario was recognised by McKenzie (1981) in his postural syndrome (see Box 12.1). He recommends fully stretching ligaments and surrounding tissue following injury.

Muscle imbalance leads to altered biomechanical stresses in joints which may precipitate cartilaginous degeneration and stiff or hypermobile joints (Marks 1993). Often, in the spine, one segment becomes damaged or degenerative as the stress it experiences is altered from that which the joint was designed to withstand. The accompanying inflammation causes fibrosis and stiffening so an adjacent joint becomes hypermobile and painful in an attempt to maintain normal functional movement. A common example of this is where stiffness of thoracic vertebral joints 1–4 causes pain at cervical 5–6, as is typical in cervical spondylosis, recognised by the forming of a ‘ledge’ between C6 and C7 and a so-called ‘dowager’s’ or ‘buffalo’ hump. Adaptation takes place in ligaments and muscles to guard the painful area, and symptoms can be produced from these soft tissues. The loading on muscles may produce spasm, fibrosis and the development of myofascial trigger spots (Travell & Simons 1992), and further postural adaptation may result.

It eventually becomes difficult to understand which changes occurred first—habitual posture, joint dysfunction or occupational stress—and a complete treatment regimen must address all aspects: correcting poor posture and poor ergonomic habits, freeing joints and their surrounding tissues, and settling soft tissue symptoms. Treatment that addresses only some facets of the problem will have only limited success. Weintraube (1986) states that treating only secondary soft tissue changes will remove compensatory mechanisms and may worsen symptoms. He suggests that, under chronic conditions, the joints should be treated first to balance the joint and soft tissue changes.

A recent and rigorously controlled study which compared massage, acupuncture and self-care education for chronic low back pain had surprising results. Patients in each of the treatment groups received therapy appropriate to their condition, thus following normal clinical practice. Treatments lasted 10 weeks, the patients being assessed at week 4 and week 10. The massage group scored significantly better than the other groups throughout the trial. A follow-up one year later showed massage and self-care scored almost equally. Acupuncture did not even achieve a significant placebo effect (Cherkin et al 2001).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree