Neurocognitive disorders

James Siberski

Introduction

Dementia affected 36 million people around the world in 2010; in 2030 that number will rise to 65 million (Hughes, 2011) and will continue to increase unless interventions are developed. With regard to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) alone, unpaid caregivers provide 210 billion dollars’ worth of care, and total reimbursement payments for healthcare for all of the dementias are projected to be $1.1 trillion in 2050 (in 2012 dollars) (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). It can be said that the dementia crisis is upon us.

When discussing the rehabilitation of individuals diagnosed as being demented one needs to define what was or is dementia. In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association published their updated Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, DSM 5, which will effectively eliminate the term dementia. It will be replaced with the term ‘neurocognitive disorder’ (NCD). The DSM 5 will also split the NCD category into three broad syndromes: Delirium, Minor NCD and Major NCD.

The proposed revision for a Delirium is:

The proposed revision for a Minor Neurocognitive Disorder is:

The proposed revision for a Major Neurocognitive Disorder is:

Once the clinician makes the diagnosis of Minor NCD or Major NCD, the clinician must then utilize the proposed criteria for the etiological subtypes of Minor and Major NCD, which are listed below:

Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Alzheimer’s Disease

Frontotemporal Neurocognitive Disorder

Neurocognitive Disorder with Lewy Bodies

Vascular Neurocognitive Disorder

Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Traumatic Brain Injury

Substance/Medication-Induced Neurocognitive Disorder

Neurocognitive Disorder Due to HIV Infection

Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Prion Disease

Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Parkinson’s Disease

Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Huntington’s Disease

Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition

Major or Mild Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Multiple Etiologies

Unspecified Neurocognitive Disorder.

There have been positive and negative views expressed from many quarters concerning the DSM 5 proposed changes. Suffice it to say that change is always difficult, costly and confusing to both professionals and patients. Professionals will need to become familiar with DSM 5 NCD in order to explain these changes to their patients.

Adding to the confusion, the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging (NIA), for the first time in over 27 years, have changed the staging of AD. As a result of recent research, it is now understood that AD progresses on a spectrum with three stages. In the preclinical stage, where the brain changes, there are no symptoms, as it starts years, if not decades, before the early symptoms of AD become apparent. An upcoming section of this chapter on lifestyle rehabilitation will elaborate. The middle stage, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), is a term not used in DSM 5, which may initially confuse professionals and surely baffle patients. The final stage, AD, is marked by symptoms of cognitive decline or dementia. The Alzheimer’s Association and NIA staging employs the term dementia while DSM 5 does not, perhaps creating a bit more confusion (Siberski, 2012).

Neurocognitive disorders and assessment

A rehabilitation program should begin with a competent assessment, with the primary goal being an accurate and early diagnosis. It must first be determined if there is a NCD or if the issue is a normal age-related change or perhaps even a delirium as the management strategies differ from those that would be utilized in a NCD. Once a NCD is diagnosed, the cause of the minor/major NCD must be determined in order to start the rehabilitation course. In a cortical NCD, such as Alzheimer’s dementia, the patient’s executive function could be normal, especially in the early phases of the disease. In a frontal–subcortical NCD, such as NCD due to Lewy bodies, executive function would be impaired. This information is important to the treatment and rehabilitation strategies a therapist would utilize (Mendez & Cummings, 2003). The diagnostic workup should include the following components:

comprehensive history to look at cognitive and functional difficulties;

medication review to see if medication(s) could be causing the problem;

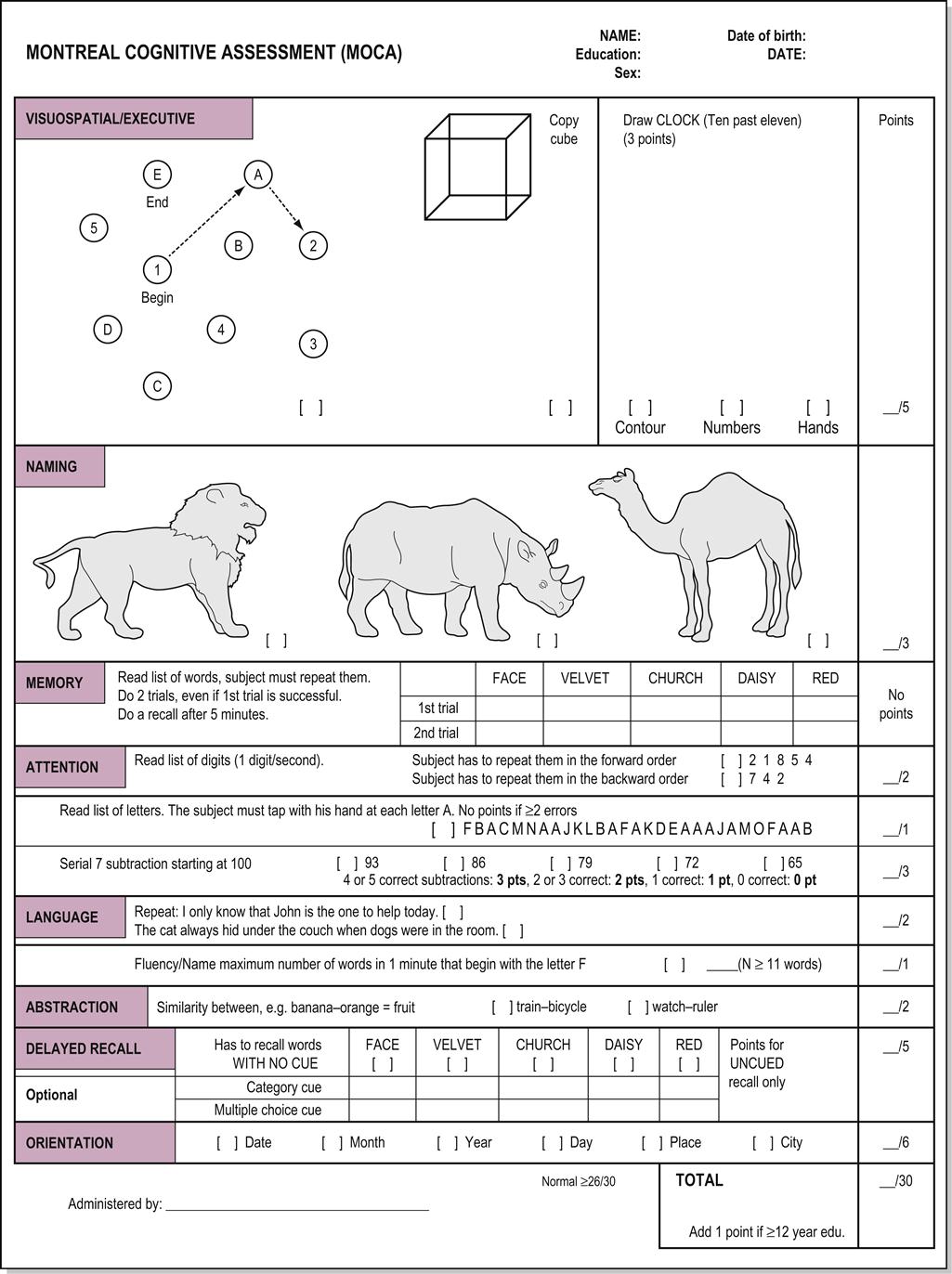

Newer instruments, such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Fig. 28.1), a screening tool developed to assist clinicians in detecting MCI, which the MMSE is unable to screen for, are gaining credibility because of improvements in sensitivity and decreasing susceptibility to cultural and educational biases. The MOCA offers the advantage of testing multiple cognitive domains with an easy scoring system and is free for clinical use (www.mocatest.org). The MOCA probes all four lobes of the brain. The MOCA is available in many different languages and comes with instructions and scoring (Galvin & Sadowsky, 2012).

Rehabilitation and neurocognitive disorders

A working definition of cognitive rehabilitation is ‘Cognitive rehabilitation (CR) aims to enable people with cognitive impairments to achieve their optimum level of wellbeing by helping to reduce the functional disability resulting from damage to the brain’ (Clare, 2012).

Contributions can be made by various clinicians, e.g. physical therapist, occupational therapist and nurses, by providing interventions at any phase of the cognitive decline in order to enhance patient participation in activities of daily living (ADLs) and communication to minimize caregiver burnout. The key strategy is to build on the patient’s intact skills, to explore new possibilities for communication and to create a sense of safety and enjoyment that includes modified ADL tasks for the patient. The clearest means of communication is to relate in ways that allow the person to feel emotionally safe and to build from an emotional tone that is perceived by the patient as being nurturing and positive.

Empowering the patient during interactions with caregivers and family means that individuality and a sense of safety and self-determination are the most important outcomes for each interaction. For staff and family, this means that there is a need to become aware of what works for the patient and what the patient can emotionally sense if the intention of the caregiver is to support their confidence and self-esteem.

The therapeutic interventions that are required for a person with an NCD necessitate that the therapist be trained beyond the entry level. When a therapist or assistant is interested in working with older individuals with cognitive impairment, advanced training in kinesthetic contact, communication, procedural learning, neurological rehabilitation and handling skills is necessary. Emphasis on mastering neurological rehabilitation techniques to empower the patient through functional training and kinesthetic cueing is critical. The therapist works closely with caregivers to enhance the effectiveness of daily tasks that are important to the patient. Patients should always be seen for treatment in their own environment, if possible, and any new therapists should be introduced by someone who has a history of months of nurturing contact with the patient (Willingham et al., 1997; Van Wynn, 2001; Holtzer et al., 2004).

Rehabilitating lifestyle

The modification of risk factors has been cited as a cornerstone for NCD prevention until medication can be developed that will prevent or stop the progression of NCD. In order to accomplish this, individuals will have to rehabilitate their lifestyles. Evidence suggests that lifestyle factors for cardiovascular disease are contributors to the development of NCDs, particularly AD and NCD due to vascular disease. Lifestyle rehabilitation that addresses issues such as obesity, high cholesterol, diabetes, high blood pressure and smoking could be effective in preventing or postponing the development of NCD (Desai, 2010). Dr Gary Small, the director of the UCLA longevity center, in his book The Alzheimer’s Prevention Program, noted that the three most important words in AD prevention are timing, timing, timing. In the book, Dr Small states:

A particular brain-protective treatment that is effective at one point in time can be less effective if we wait too long to use it. In fact some therapies may even be harmful if the timing is slightly off. The most effective point in time for using a certain treatment may be years, even decades, before any symptoms of mental decline are noticeable.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree