Neuroblastoma

Douglas R. Strother

Heidi V. Russell

Neuroblastic tumors, which include neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma, develop from neural crest tissue. They cover a spectrum from highly malignant to benign in both histologic appearance and clinical behavior. The most common presentation of the disease spectrum, disseminated neuroblastoma, has distinctly different behavior in children under 1 year of age (infants) compared with histologically identical disease in older children. Particularly in infants, the regression of primary and metastatic disease may occur spontaneously or after surgical resection of the primary tumor. In the older child, metastatic neuroblastoma usually is fatal, despite sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Newborn screening for disease through the measurement of urinary catecholamines has failed to reduce the mortality associated with advanced-stage neuroblastoma.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid tumor in children and is the most common malignancy in the first year of life. It is slightly more common in boys, and its incidence is 10.4 per 1 million white children per year and 8.3 per 1 million black children per year. The median age at diagnosis is 17.3 months; approximately one-third of cases are diagnosed by the age of 1 year, 80% by 4 years, and 97% by 10 years. Overall, approximately 600 new cases of neuroblastoma are diagnosed each year in the United States.

The cause of neuroblastoma is unknown; environmental exposures have not been shown to be causative. Genetic predisposition through mutation of a germinal cell may play a role in approximately 20% of all cases. In addition, multiple cases of neuroblastoma have been described within families, and in these patients, tumors occur at a younger age and are more often multifocal.

PATHOLOGY

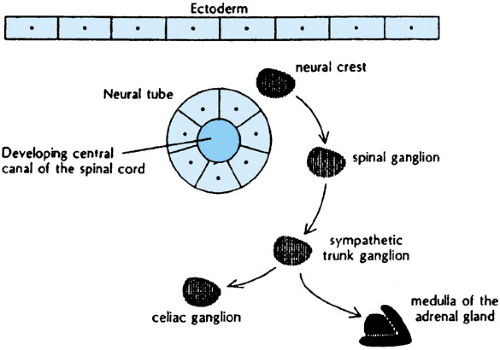

Derivatives of neural crest tissue include the adrenal medullae and sympathetic nervous system ganglia. The different histologic patterns of neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma correlate with normal patterns of differentiation of these tissues (Fig. 308.1).

Neuroblastoma is one of the pediatric small, blue, round-cell tumors, and is the most primitive appearing of the spectrum of neural crest tumors. Differentiation is either lacking altogether or present in less than one-half of tumor cells. Electron microscopy may reveal neurosecretory granules, microfilaments, and microtubules. Tumors with more than 50% of cells showing gangliocytic differentiation are called ganglioneuroblastoma. The degree of differentiation may vary within a tumor, and histologic examination of the entire tumor is required to distinguish this tumor from the other histologic extremes. The benign form of neuroblastic tumors is called ganglioneuroma. These tumors are comprised of mature ganglion cells, neuropil, and Schwann cells. Tumors may originate as ganglioneuromas or, alternatively, evolve through spontaneous or therapy-induced differentiation of more malignant disease.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

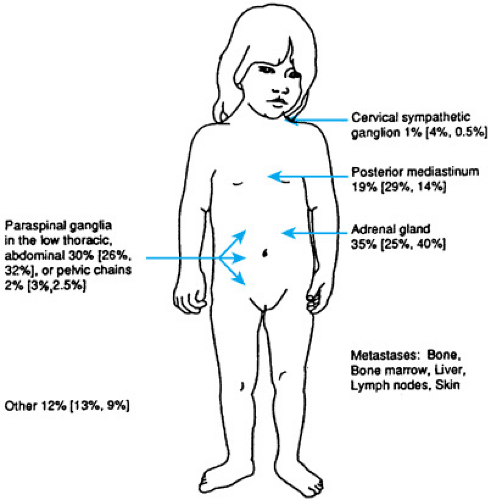

Neuroblastic tumors may arise from anywhere in the sympathetic nervous system (Fig. 308.2). Two-thirds of cases arise in the abdomen, nearly evenly distributed between the adrenal glands and paraspinal sympathetic ganglia. Tumors in the chest and neck are more common in infants. Tumor may metastasize to lymph nodes, liver, bone, bone marrow, and skin. Brain and lung parenchyma rarely are involved at diagnosis. Symptoms of neuroblastoma result most commonly from mass effect at sites of involvement. Nonmetastatic disease may present with pain or a palpable mass. Intrathoracic disease commonly is diagnosed incidentally during an evaluation for trauma or possible infectious disease. Manifestations of metastatic disease include fever, pain, periorbital ecchymoses and proptosis, abdominal distention, lymph node enlargement, pallor, weight loss, and failure to thrive. Metastatic skin nodules occur in infants and are bluish, palpable, and nontender. Compression of the spinal cord at any level by extension of tumor through neural foramina may result in pain, paresis, or paralysis. Less common but classic manifestations of neuroblastoma include Horner syndrome, obstruction of the superior or inferior vena cava, and paraneoplastic syndromes that result in secretory diarrhea or opsoclonus-myoclonus. Symptoms secondary to production of catecholamines are uncommon.

DIAGNOSIS

Neuroblastoma usually can be suspected by the clinical presentation. Histologic confirmation is required, however, and can be accomplished from biopsies of either primary or metastatic disease. In addition to a histologic analysis of tumor, assessing tumor for various indicators of biologic behavior is helpful (see section, Tumor Biology) so that appropriate therapy can be assigned.

More than 90% of neuroblastomas produce the measurable urinary catecholamines homovanillic acid (HVA) and vanillylmandelic acid (VMA). Levels can be assessed accurately on a few milliliters of urine. When the histologic assessment of tumor is impossible, the diagnosis of neuroblastoma may alternatively be made by the finding of cells compatible with neuroblastoma in the bone marrow of a patient with radiographic evidence of disease and urine levels of HVA and VMA that are elevated to more than three standard deviations above the mean values for age.

Staging

Staging of disease should include an evaluation of the primary tumor and all possible metastatic sites. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis usually is done at diagnosis, although plain chest radiography and abdominal ultrasonography are used occasionally. The skeletal system is evaluated through nuclear bone scanning and bone radiography. Bilateral bone marrow aspirates and biopsies complete staging. Spinal MRI is useful when compression of the spine is suspected. More centers are using whole-body imaging with radiolabeled 131I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine to evaluate all sites of disease.

Until the late 1980s, a variety of staging systems were used throughout the world to designate the extent of disease. Although comparable in many aspects, variations among them made direct comparison of clinical trial outcomes very difficult. In 1987 and 1990, representatives from around the world met to formulate and revise, respectively, a uniform staging system based on clinical, radiographic, and surgical evaluations of children with neuroblastoma. The International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS) resulted (Box 308.1). Use of the INSS will greatly aid in the development of new clinical trials and in the analysis of potential new prognostic variables.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree