Neoplasms of the prostate

Stephen A. Gudas

Incidence

Prostate cancer is the most common male cancer in the US, accounting for approximately 32% of all newly diagnosed cancers in men (Siegel et al., 2013). It is also the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men in the United States of America, accounting for 13% of all male cancer deaths (Koys & Bubley, 2001; Calabrese, 2004). In 2005, it is estimated that there were 238 590 new cases of prostate cancer diagnosed in the US, with 29 720 deaths (Siegel et al., 2013). The rates of prostate cancer vary between different populations (Table 38.1), and there are factors that may lead to familial clustering of cases (Gronberg, 2003). The median age of onset is 70 years, making it a distinct geriatric problem; the incidence increases for each decade after the age of 50. It is a curious fact that the incidence of prostate cancer peaked in the mid 1990s and has decreased slightly since that time (Brawley, 2012).This is rather constant across cultures and countries, although the incidence of frank prostatic cancer is low in Japan, for example. With the aging of the population, it is expected that the incidence of prostate cancer will rise.

Table 38.1

Worldwide variation in rates of prostate cancer deaths, 2010

| Country | Crude Rate Per 100 000 Population |

| Australia/New Zealand | 27.4 |

| Canada | 22.5 |

| China | 0.9 |

| Ecuador | 11.46 |

| Egypt | 1.57 |

| Iraq | 1.5 |

| Republic of South Africa | 9.5 |

| United Kingdom | 33.5 |

| United States of America | 22.8 |

Source: Cancer Mondial, 2013.

Although the exact etiology of prostate cancer is unknown, there appears to be a hormonal relationship as many tumors respond to orchiectomy, implying that testosterone augments cancer growth in men. Cancer of the prostate has been found to occur at a disproportionately higher rate in certain industrial workers – those who work with cadmium, tire and rubber, and sheet metal (Carter, 1989). Familial factors may play a role but this has not been fully elucidated.

Clinical relevance

Almost 60% of prostate cancer patients will have clinically localized cancer at diagnosis, making cure a real possibility. Frequently, resectable tumors are asymptomatic or patients have a few symptoms of urinary tract obstruction, such as difficulty in initiating and/or stopping micturition. In the absence of infection, marked bladder symptoms should warrant a search for prostate cancer. If the clinical presentation is advanced, there will be symptoms of bladder outlet obstruction and anuria, uremia, anemia and anorexia will ensue. Patients are very ill at this juncture and most will have sought medical attention.

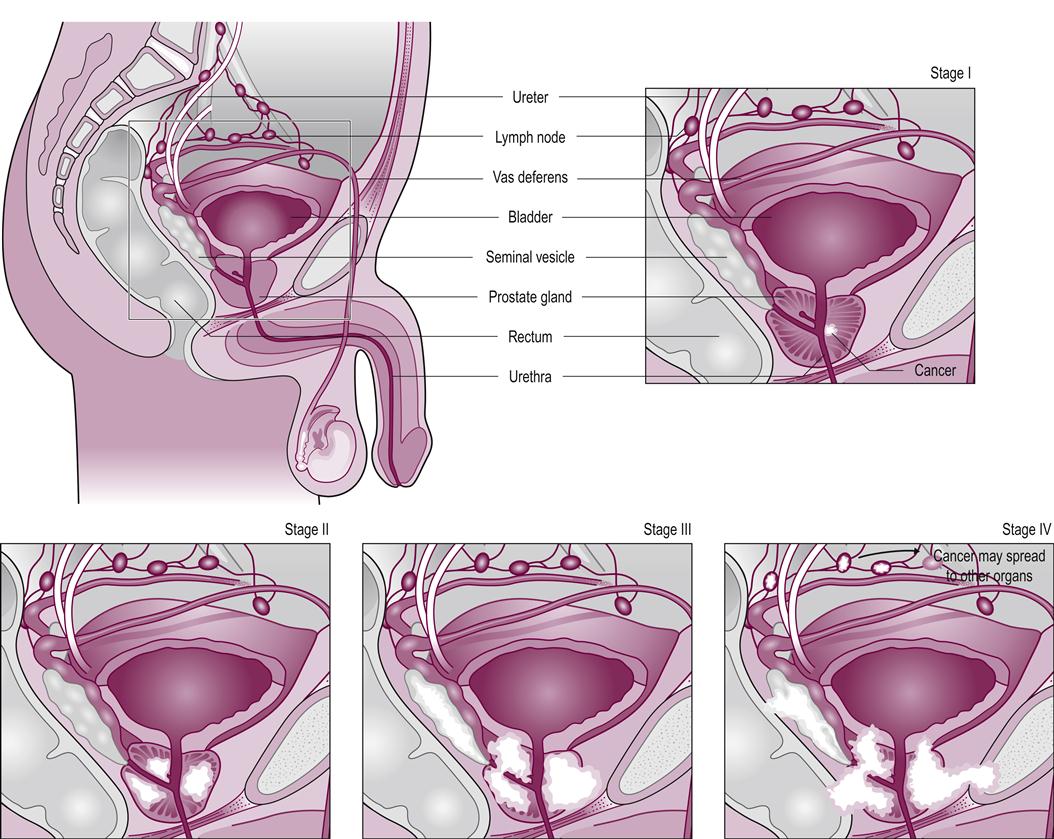

The digital rectal exam still finds most primary prostate cancerous tumors. Approximately 50% of palpable nodules in the prostate are proven to be carcinomas. The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a prostate marker that is useful in the early detection of prostate cancer (Catalona et al., 1991; Stenman et al., 2005). PSA levels are determined after a nodule is palpated on digital examination. If the level of PSA is above 10 ng/ml, there is a 66% chance that a subsequent biopsy will be positive. PSA levels are widely used as a screening tool for the general geriatric male population, but the PSA is a prostate specific antigen, not a prostate cancer specific antigen, and thus can be elevated in other conditions (Heinzer & Steuber, 2009). A baseline PSA should be taken in men after the age of 50 and repeated at intervals. Continued investigation will be necessary to determine the true value of both screening and clinical staging procedures (see Fig. 38.1 for a representation of staging for prostate cancer). Prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) is used to detect metastatic disease, as elevated levels signify spread to at least the lymph nodes (Syrigos et al., 2005).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree