6 Musculoskeletal infection

Cases relevant to this chapter

12, 23, 26, 27, 32–33, 68, 71, 75, 79, 91

Essential facts

1. Musculoskeletal infections occur either by haematogenous spread, or by direct inoculation through open wounds (including surgical wounds) or skin lesions.

2. Metaphyseal regions of long bones are susceptible to infection where sharp loops of capillaries predispose to bacterial deposition.

3. The commonest organism involved in musculoskeletal infection is Staphylococcus aureus, followed by Streptococcus.

4. A diagnosis of acute septic arthritis and acute osteomyelitis should be made primarily on the basis of clinical examination.

5. Antibiotics should be given for 4–6 weeks; urgent drainage is required if abscess formation has become established.

6. In chronic osteomyelitis, treatment primarily involves radical surgical clearance of all non-viable bone and granulation tissue; the role of antibiotics is less important.

7. In the case of infected joint replacements, bacteria introduced at the time of surgery may produce a biofilm around the implant and are difficult to eradicate.

Introduction

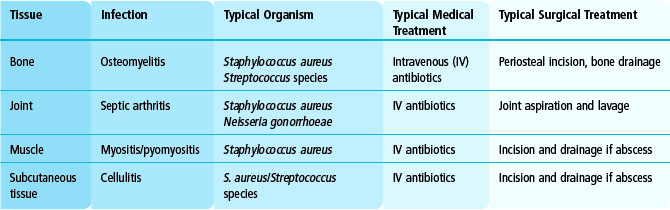

Various musculoskeletal tissues can become infected, giving rise to a variety of clinical problems (Table 6.1). The underlying causes and the basic principles of management are similar, irrespective of the tissue concerned. Here we will look at why and how tissues become infected, consider the clinical presentation, and describe the principles governing management of these conditions. Specific types of infection will then be considered in greater detail.

Specific infections

Acute septic arthritis

The clinical presentation is of pain and loss of movement in a joint together with fever and malaise. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is necessary, as articular cartilage does not survive long in the presence of a tense effusion of pus. A high index of suspicion for infection is required in all cases of an acutely swollen and painful joint, particularly in a young child. Aspiration of the joint (Fig. 6.1) may not yield the causative organism, and diagnostic imaging modalities such as radiography and ultrasonography will simply confirm the presence of a joint effusion. However, the clinical picture together with abnormally high values for the inflammatory markers should be sufficient to make the provisional diagnosis of infection. After blood cultures have been obtained, ‘best guess’ intravenous antibiotic treatment must be started and the joint drained and washed out with copious quantity of saline. At the hip, this may require open surgery, especially if the infection has become established and septation has occurred (subdivision of the abscess cavity by fibrin bands).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree