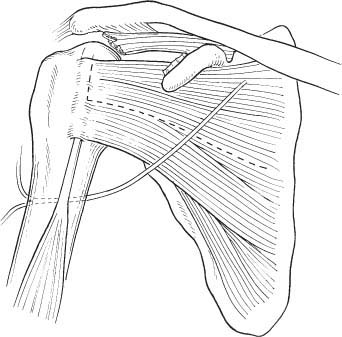

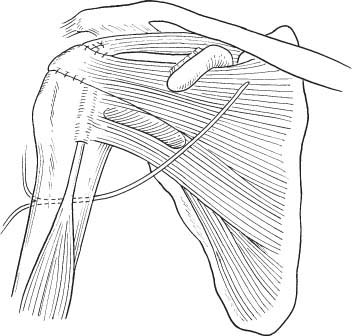

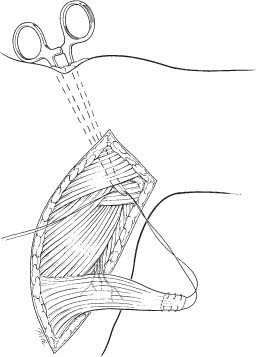

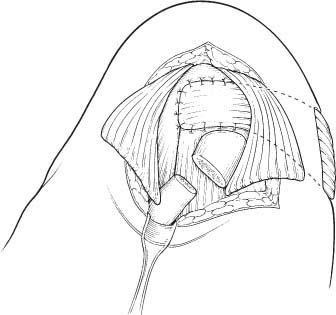

5 Muscle Transfers for the Treatment of the Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tear The main goals in rotator cuff (RC) repair are to establish continuity of the tendon, restore the soft tissue interface with the overlying acromion, center the humeral head in the glenoid, and relieve impingement.1 Failure of these goals and failure to achieve repair of the RC is thought to lead to the development of cuff tear arthropathy. A loss of normal humeral head depression, which is supplied by a balanced RC unit, results in the upward migration of the humeral head. This, in turn, alters the force vector across the glenohumeral joint, leading to early degenerative changes. Additionally, with massive RC tear the humeral head is not effectively stabilized in the anterior and posterior direction, resulting in additional abnormal sheer forces compounding the abnormal wear pattern.2 RC tear repair, in general, has demonstrated good long-term results with clinical improvements.2–10 Outcomes of repair correspond to the size or the RC tear, with massive tears presenting the most difficult surgical challenge.6,10,11 No universally agreed upon definition or treatment of a massive RC tear has been established. Cofield3 defined massive as any tear with a diameter >5 cm. Others have defined a massive tear as those tears involving at least two tendons.4 Intraoperatively, two findings are important in determining if the massive RC tear is repairable: the elasticity of the muscle and the assessment of the possibility of direct tendon reinsertion into bone after excision of the necrotic ends.5 Most large or massive RC tears are repairable; however, 5% of all RC tears are mechanically irreparable.6 Additionally, the repair of chronic, retracted tears involving two or more tendons is technically difficult and has been shown to be less successful.7–10 In those instances where mobilization and direct repair of tendons is unattainable or has failed, an additional procedure may be required. Adequate results have been obtained from simple débridement and decompression of massive RC tears and partial repairs.11,12 If débridement proves unsuccessful, then transfer of local tissues may be required to alleviate pain and improve function. Many tendon transfer techniques have been described for the management of massive, irreparable RC tear. These include mobilization of the superior cuff and transposition of the long head of the biceps tendon,11,13 supraspinatus muscle advancement,14–22 latissimus dorsi transfer,4,15–26 subscapularis transfer,3,16 trapezius transfer,17–31 teres major transfer,18–34 pectoralis major transfer,19 teres minor transfer,1 combined subscapularis and teres minor,20 and the deltoid muscle flap.21,22 Although numerous techniques have been illustrated, no gold standard exists yet. The multitude of different transfers and the variability in the results of these techniques demonstrates a general lack of consensus on optimal treatment. Within this chapter, we will explore the most commonly described tendon transfer techniques, their indications, contraindications, and results. It is important to understand the pathology present within the shoulder prior to surgery. This information should be sought preoperatively with plain radiographs in orthogonal planes, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and a thorough clinical exam. Muscle wasting in the supraspinatus fossa, weakness of external rotation (ER), and abnormal scapulothoracic motion should alert the clinician to the potential for a massive RC tear.23 Additionally, it is important to know the main complaint of the patient, their functional status, and expectations from reconstructive surgery. Armed with this information the surgeon can best plan which reconstructive procedure to utilize. Subscapularis transfer is used for massive RC tears that cannot be primarily repaired. Because this transfer has been associated with diminished active elevation postoperatively, it is best performed on those unable to elevate the extremity above their head or in whom overhead function is markedly impaired.24 Additionally, the patient should have a subscapularis amenable to mobilization. Therefore, the ideal patient for subscapularis transfer has a massive tear that is not amenable to primary fixation, cannot elevate the arm, and has an adequate subscapularis musculotendinous unit. Cofield3 first described the subscapularis transfer in 1982 for patients with tendon deficiency preventing primary repair. Through an anterior deltoid approach, the deltoid is elevated from the anterior acromion with care to provide a good sleeve for repair. An anterior acromioplasty is performed with resection of the coracoacromial ligament and decompression of the subacromial space and supraspinatus outlet. A limited débridement is performed to obtain a good vascular edge for healing. The upper half to two thirds of the subscapularis is mobilized by incising the musculotendinous junction in an oblique manner downward and medially (Fig. 5–1). The subscapularis can be divided due to its dual innervation from the superior and inferior subscapular nerves. The distal half of the subscapularis is left intact as an important passive and dynamic stabilizer of the shoulder. Soft tissue attachments are detached, while protecting both the axillary and musculocutaneous nerves. The upper part of the subscapularis is advanced superiorly and laterally to a cancellous trough medial to the greater tuberosity. The free edge is secured into the cancellous trough and the trimmed bleeding edges of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus are sewn to the transferred subscapularis to close the defect (Fig. 5–2). Finally, the shoulder is ranged to evaluate the repair and ensure that the transfer is not overtensioned.24 Postoperative management requires closely supervised physical therapy. Intraoperative ROM should guide postoperative physical therapy. Passive ROM and pendulum exercises are initiated immediately to prevent adhesions or contractures. ER is avoided as the subscapularis is mobilized superiorly and will be put under tension. Active ROM is initiated at 6 weeks; ER is begun at 2 to 3 months. In Cofield’s3 initial series of 29 patients, 10 underwent subscapularis transfer for degenerative RC disease. Half felt that they improved significantly, whereas the other half felt they were only slightly improved and the average postoperative active elevation was 130 degrees. RJ and TJ Neviaser36 found that transfer of the subscapularis and teres minor was a good salvage procedure for a massive RC tear providing decreased pain and improved function if the deltoid was intact. They found deltoid dysfunction in three out of five failures. In 1983, Neer25 described use of the upper 70% of the subscapularis for closure of large superior defects. In a series of 33 patients followed for a mean of 4.5 years, 16 had excellent results while 9 were satisfied and 9 were unsatisfied. The unsatisfied group primarily complained of decreased strength. Karas16 felt caution should be utilized in selecting patients to undergo subscapularis transfer due to the potential for loss of function. In a retrospective review of 20 patients who underwent subscapularis transfer and subacromial decompression for massive, irreparable RC tears, Karas noted that 17 out of 20 patients were satisfied at a mean of 30 months. Nineteen described a decrease in pain postoperatively; 9 patients still had weakness and pain with prolonged overhead activities. Two patients lost active elevation despite reduction in pain and felt that the operation made them worse—possibly due to the loss of stabilization of the humeral head.16,24 The transfer provides excellent pain relief, but caution should be exercised in doing this transfer in patients who have intact overhead function because this has been shown to potentially deteriorate.16,24 Figure 5–1 The upper one half to two thirds of the subscapularis is incised from its insertion on the lesser tuberosity. A bone trough is prepared for insertion of the transferred tendon onto the greater tuberosity. Figure 5–2 Completed subscapularis transfer. The medial edge of the transferred subscapularis tendon is sewed to the remnant lateral edge of the supraspinatus. Laterally, the subscapularis is attached to the greater tuberosity with suture anchors or transosseous sutures. Subscapularis transfer is not without potential complications. The subscapularis acts as a humeral head depressor due to its insertional relationship into the lesser tuber-osity. With transfer of the proximal half to two thirds of the subscapularis, there might not be enough force to depress the head actively, while the deltoid elevates the arm. With the subscapularis transferred superiorly, the anterior force vector may not be able to balance the posterior force vector. Additional potential complications include injury to the musculocutaneous nerve and the axillary nerve as it crosses the subscapularis. An additional theoretical complication is anterior instability resulting from transferring the upper half to two thirds of the subscapularis superiorly leaving only the lower third intact. While mobilizing the subscapularis, it is important not to violate the anterior capsule to protect against anterior instability. Overall, subscapularis transfer is a useful procedure when the RC cannot be closed by conventional methods. However, the surgeon should be aware of the potential loss of forward elevation after subscapularis transfer. Furthermore, subscapularis transfer violates what is often the only intact, functioning, major muscle unit in patients with massive RC tear. Healing complications or rupture of the transferred muscle unit may result in no intact muscle group about the glenohumeral joint. For this reason, subscapularis transfer should likely not be the first choice in one’s armamentarium for muscle transfer in massive RC tear. The latissimus dorsi transfer was conceived to allow closure of the RC defect with a vascularized, autogenous tendon, while providing head depressor activity and restoration of ER.15 Originally a treatment for poliomyelitis and brachial plexus injuries, the transfer was intended to partially restore abduction as well as stabilization of the glenohumeral fulcrum.26–45 The latissimus dorsi is a strong extrinsic internal rotator and adductor of the humerus, which receives its innervation from the thoracodorsal nerve and its vascular supply through the thoracodorsal pedicle lying on the anterolateral surface of the muscle. Saha27 determined that the latissimus is active throughout shoulder ROM, so synergy with a new function is attainable with proper muscle retraining and rehabilitation. Zachary28 reported the first case of a latissimus dorsi transfer in a child with brachial plexopathy. He transferred both the latissimus and the teres major to the posterior humerus to improve ER. In 1988, Gilbert et al29 and Gerber et al30 reported on the technique of latissimus dorsi transfer for loss of ER and superior humeral head migration in patients with massive RC tears. A massive defect of the RC is biomechanically similar to motor loss of the suprascapular nerve, thus a latissimus dorsi transfer provides abduction, ER, and depressor forces to the glenohumeral joint. The primary indication for latissimus transfer is ER weakness due to loss of infraspinatus function. Pain and forward elevation loss are relative indications for latissimus transfer. Although not an absolute contraindication, Gerber et al noted that those patients with subscapularis insufficiency fared less well after latissimus dorsi transfer. The patient is draped in the lateral decubitus position and a lateral incision across the axilla is utilized. The latissimus dorsi is mobilized extensively along its superficial margins and mobilized off the scapula. The neurovascular pedicle is identified along the anteroinferior margin and protected along its course. The insertion of the latissimus dorsi is visualized by humeral abduction and internal rotation (IR). The tendon is then resected at its bony insertion. Care must be taken to avoid injuring the posterior humeral circumflex artery at the superior edge of the tendon. The radial nerve and axillary nerves are at risk during the tenotomy due to their proximity.31–53 The tendon is mobilized to reach the posterosuperior aspect of the RC with the shoulder in 60 degrees of abduction. Not infrequently, the tendon may be short or thin, requiring augmentation with autogenous fascia lata. The tendon must track medial to the instant center of rotation of the shoulder joint throughout its arc of motion (Fig. 5–3). To maintain this path, the inferior enveloping fascia of the posterior deltoid may be used as a pulley. This will prevent lateral subluxation of the tendon; if it slips laterally it will become a primary adductor of the humerus. The tendon can then be sutured to the existing cuff tissue or used to close the defect as needed (Fig. 5–4). ROM is protected in an abduction brace for 6 to 8 weeks followed by gradual ROM and strengthening. Gerber and colleagues30 have demonstrated encouraging results with the latissimus dorsi transfer. They reported on 69 massive RC tears treated with latissimus dorsi transfer reviewed at an average of 53 months.30 They found a significant improvement in pain, active flexion, active abduction, and active ER. Abduction strength also improved postoperatively. In this series, however, 13 patients with subscapularis insufficiency had minimal improvement in their postoperative outcome. The authors noted that the procedure may be of limited benefit to those patients with a positive lift-off test preoperatively. Figure 5–3 Passage of the transferred latissimus dorsi tendon deep to the posterior deltoid. The fascia of the posterior deltoid may be used as a “sling” to maintain a medial orientation of the tendon to the glenohumeral joint’s instant center of rotation. Figure 5–4 Attachment of the transferred latissimus dorsi tendon to the humeral head. When possible, the distal edge of the tendon should be attached to the superior aspect of the subscapularis tendon. Medially, the tendon is sewn to the remnant rotator cuff. Laterally, suture anchors or transosseous sutures are utilized to attach the latissimus tendon to the greater tuberosity. Aoki et al32 prospectively reported on 12 shoulders that underwent latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable cuff defects. Good to excellent results were found in eight cases, fair in one case, and poor in three cases. Function and pain were significantly improved. The mean postoperative active forward flexion was 135 degrees, which represented a 36-degree improvement from mean preoperative measurements. Osteoarthritic changes appeared in five shoulders and proximal migration of the humeral head occurred in six. Aoki and colleagues theorized that these changes occurred because the depressor action on the humeral head might not have been fully restored due to the latissimus dorsi not being fully active in the early phase of elevation. Electromyography revealed that 75% of transferred muscles showed synergistic action with the supraspinatus. Nonsynergistic motion was evident in three shoulders and was theorized to result from adhesions or rupture. Nonsynergy was associated with poor results. Risk factors for poor outcome were identified as multiple previous surgeries, deltoid pathology, and involvement of the subscapularis in the cuff defect.32 Miniacci and MacLeod33 retrospectively reviewed 17 patients who were treated with a latissimus dorsi transfer for a massive RC tear. At a mean 51 months follow-up, 14 patients had significant pain relief and significant improvement in function for all activities except lifting more than 15 pounds. Fourteen stated they would have the operation again. Seven of 8 patients with a detached or nonfunctional anterior portion of the deltoid also had improvement. Interestingly, the authors of this series noted that insufficiency of the subscapularis did not adversely affect postoperative outcome. There were three failures due to ongoing pain and impaired function. These 3 patients all had work-related injuries and viewed the operation as a failure. Warner and Parsons34 evaluated the efficacy of primary transfer of the latissimus dorsi versus transfer as a salvage reconstruction for failed repairs. Salvage reconstruction of a failed prior RC repair yielded inferior results when compared with a primary latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable RC tear. Warner and Parsons reviewed 16 patients who underwent transfer as salvage after a failed repair and 6 patients who underwent primary reconstruction. The salvage group had lower Constant scores (55 versus 70) and a higher rate of late rupture (44 versus 17%) compared with the primary group. Postoperative active forward flexion and ER were 122 degrees and 41 degrees in the primary group, with 105 degrees and 40 degrees in the salvage group, respectively. Inferior outcomes were found in patients with poor quality tendon, severe fatty degeneration, and deltoid detachment. Results of primary transfers in Warner and Parson’s series were comparable to Gerber et al’s series as 83% had good to excellent results. Lower gains were realized when utilized as a salvage procedure with only 50% reporting good to excellent results and 20% reporting poor outcomes. Warner and Parsons concluded that a competent deltoid is mandatory for the restoration of shoulder function once the tendon transfer achieves humeral head coverage. Patient selection is critical to this outcome. The authors noted that results similar to primary cases can be had with salvage only if the deltoid is intact. Based on the encouraging results obtained by Gerber and others, the latissimus dorsi transfer has undergone increasing acceptance for posterosuperior tear configurations in patients that have limited ER and elevation with an intact subscapularis. Subscapularis tendon tears are rare and account for 3.5 to 8% of RC tears.35,36 They are sometimes associated with anterior shoulder instability and respond poorly to non-operative management.35,37 Diagnosis is difficult and often causes a delay in treatment and a subsequently more-complex repair.19,37–60 Gerber et al found that subscapularis tendons repaired early had better results than those with a delay to repair.38 If left untreated, the subscapularis might not be amenable to repair due to retraction and atrophy. Pain may be accompanied by instability and abnormal glenohumeral kinematics.39 Various transfers have been attempted for subscapularis tears, but the pectoralis major has had the most attention.6,15,19,40–64 Wirth and Rockwood originally described transferring the superior half of the pectoralis major tendon to the humeral head for reconstruction of a massive RC tear.19 Resch et al41 modified this transfer to approximate the natural course of the subscapularis more accurately. Through a deltopectoral approach, the subscapularis, the conjoined tendon, tendon of the pectoralis major, and the anterior humeral head are all visualized. The long head of the biceps is tenotomized and tenodesed in those where it is dislocated anteriorly, and the superior half to two thirds of the pectoralis major is detached from the humerus and mobilized. Due to the segmental distribution of the thoracoacromial artery and pectoral nerve after passing under the clavicle, this does not compromise the neurovascular status of the pectoralis.42 The musculocutaneous nerve and its entrance into the coracobrachialis muscle is identified and the space posterior to the conjoined tendon is developed. The pectoralis major tendon is then passed behind the conjoined tendon and anterior to the musculo-cutaneous nerve. Transosseous nonabsorbable sutures or suture anchors are utilized to attach the transferred pectoralis major (Fig. 5–5

Subscapularis Transfer

Surgical Technique

Latissimus Dorsi

Surgical Technique

Pectoralis Major Transfer

Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree