Motor function in feeding, dressing, toileting, washing, bathing, play and communication

Those below are of particular significance, although all motor functions are needed (see Levitt 1994).Activate the motor abilities at a child’s developmental stage, with and without equipment (see Chapter 9). See section ‘Parent-child interaction’ in Chapter 2 and section ‘Emotions and learning’ in Chapter 6.

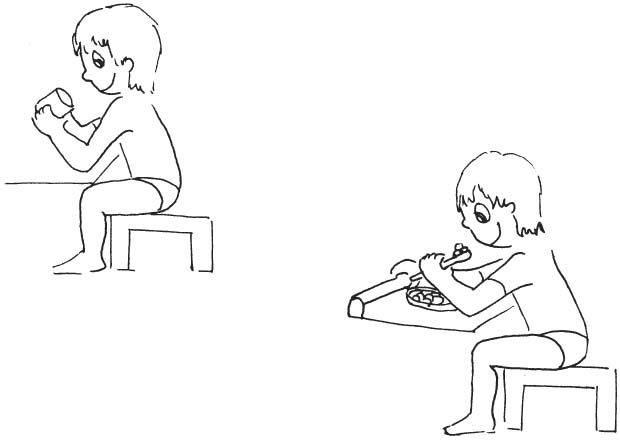

Vertical head control, sitting on the floor and/or sitting on a chair of the correct size and design

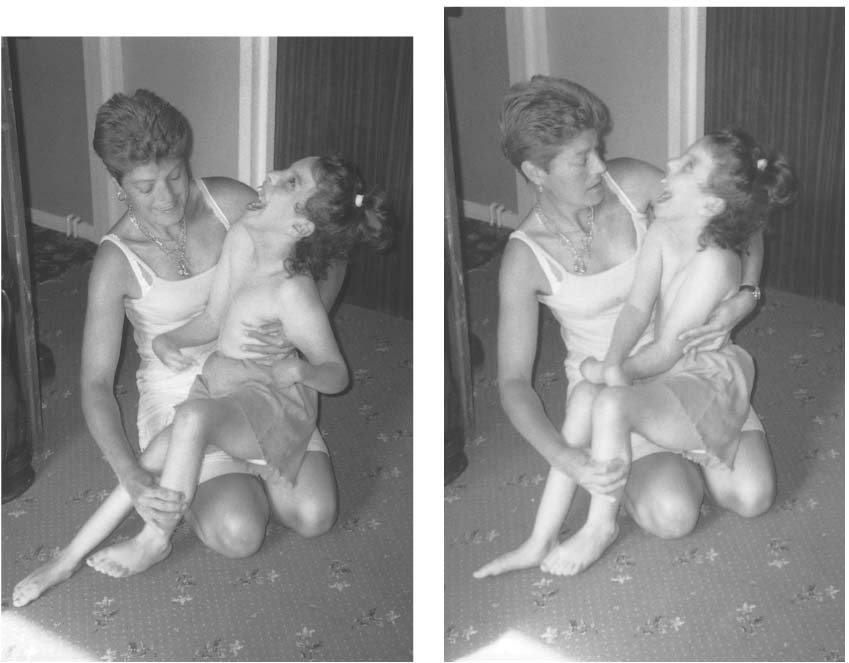

Obtained by: holding the child’s shoulders forward with your arm when a baby or severe child sits on your lap or next to you on his chair. In an older person, hold his shoulders forward with your arm for vertical head control in a forward position. You may need to support his chin. Later, face the child hold his arms stretched forward across the table between you, or hold him in weight bearing on his forearms. It is best if he can use his own support by either his grasping bars or table edge with both hands and straight arms. A child may be able to lean against a rounded edge of a table or onto his forearms on the surface. Bars or rails may be vertical or horizontal according to a child’s ability. They are attached to the table, wall, bath, near the toilet/potty and stable toy shelves for daily activities (Figs 10.1–10.3). These positions are adapted for feeding, drinking, face washing, hair brushing, and pulling off top clothes. Positioning facilitates a child’s use of vision, of hearing and for communication. Children are well positioned to socialise, including participation within music and other groups. When a child has the ability, he releases one hand whilst the other holds on or remains leaning on a surface for balance.

A child is also more able to play with toys as he stabilises himself on one arm and hand or just leans against a stable table. With improving balance, a child may sit astride his own chair and grasping its rungs for communication, play, dressing and feeding. Support may be needed for some children from behind by your sitting there and holding the child forward. They may reach a stage when they only need your stabilising hand at a child’s pelvis. You may stabilise a child with your knees, or with your feet and knees, if you are sitting at a higher level to a child on a box or on the floor. In these positions a child can develop head and trunk control with or without using your or his own arm–hand support.

Sitting with support to the child’s pelvis may be carried out with groin straps, diagonal strap across the hips or by firm pressure with an adult’s hand in the lower area of the child’s back, and later just holding his hips. The child can then carry out an activity whilst activating control of head, trunk and hands. Sitting on a cushion against a wall, in a corner of a wall or sofa and on a variety of chairs and boxes increases a child’s experiences and used for those children who can function in all or some of them.

Remember to avoid slumping of the child or sliding down the seat during activities. Readjust the child’s hips to be well back in a seat. Abnormal postures interfere with hand function, trunk and head control needed for daily activities (Fig. 10.3).

Standing or kneeling upright is used for painting, drawing, washing, toileting for boys, dressing and for many play activities. Sometimes eating and drinking is easier in supported standing. Standing at the levels of a child’s peers increases communication and socialisation and increases visual and spatial experiences.

Obtained by: use of horizontal, sometimes vertical, rails on tables, walls, blackboards, easels, leaning against stable furniture and holding rungs of a chair. Standing frames are used initially, although more severe children may need them for many years.

Prone position or on hands and knees are other positions in which a child manages playing and communication with others on the floor, as well as when participating in dressing and drying after being washed. Head and arm control and partial rolling are activated for activities. On hands and knees may be needed for play with cars and trains, gardening, housekeeping activities, in sandpits and drawing or painting on the floor.

Figure 10.3 (a, b) Positioning for communication with postural alignment (see same child in Fig. 9.68).

Obtained by: use of cushions, various sized wedges stabilised rolls, having a child over an adult’s lap or arms. The adult is either on the floor, or has the child on a bed/changing table for washing, drying and dressing. Persistent use of kneeling positions is not advisable for those children who sit back on their heels during the activity or who have tightly bent hips and knees.

Use of the hands is obviously required for all activities and cannot be condensed unless a particular activity is discussed in detail. Hand function is associated with postural control (see Chapter 9).

Motor function and perception

All the training for motor function is also training perception. Thus, during the motor developmental techniques the therapist needs to recognise and involve the following main features:

Tactile and proprioceptive experiences with different textures, temperatures and feeling different shapes, sizes, weights, to develop stereogno-sis. Meanings of words become associated with these experiences of what is, say, smooth, hard, scratchy, knobbly, rough, hot and cold. These basic sensorimotor experiences underlie specific learning activities such as pairing, matching, sorting, brick building and other methods for perceptual and conceptual understanding in developmental delay (Stroh et al. 2008).

Recognition of the child’s own body by tactile recognition during motor training as when touching his mouth, face, grasping his foot or clasping his hands, as well as touching others and sitting in close contact with parents and family members.

During motor training and other activities, a child can learn about his body parts by having his nails painted, putting on rings, bells, bracelets, make-up moustaches, earrings, ribbons, bandages, thimbles or play lighting up parts of his body with a torch. When handling a child in movement training, rub, stroke, use vibrating toys, ice therapy as well as words to draw attention to parts of his body.

Drawing attention to the child’s body parts leads to an awareness of his own spatial relationships or body scheme, for example where are his toes? – ‘in front’, ‘below’ and so on. This is also involved with his body planes (Cratty 1970) and which part of his body is moving and in which direction. This is experienced through sensation and proprioception, but a child needs to be made more aware of what and where he is moving in perceptual-motor learning in occupational therapy and physiotherapy. Linking many sensations in motor experiences, especially in pleasurable play, is considered of importance by occupational therapists, psychologists and teachers. Some professionals call this ‘intersensory development’.

Intersensory development is encouraged by associating the sensorimotor actions trained with hearing and vision. This is important in developing a child’s hand function. During the exploratory play with toys and objects there is linking between what the child touches and feels, grasps, sees, listens, smells, and when still mouthing, tastes. Manipulation of objects with banging, throwing, squeezing, rolling, pressing and breaking are linking many senses. These actions develop perceptual and conceptual understanding such as:

Appreciation of the qualities of objects and of their relations to one another. Using both gross and fine motor activity, a child is gaining learning experiences to understand round, square, long, cylindrical shapes and discover which fits into which, which can be placed on top of which object and also which object is nearer, further away, behind, in front of or next to the other. These perceptions and concepts are finely tuned in various selected activities in education and occupational therapy which interact with physiotherapy. The different therapists and teachers work together to offer activities to children.

Appreciation of the child’s relationship to objects and space. These perceptual experiences also become involved with motor function. As the child learns to move through space, he is also learning to appreciate how far he is from objects, how to get into and out of things, how to get on top of, under, around, behind and learn many other relationships to objects and space.

Thus, the child finds out about his body parts, their relations to each other and also the relations of his body to objects and to space during gross motor development and fine motor development.

Development of praxia, motor planning or using movements appropriate to a motor task such as dressing, writing, using a pair of scissors or other implements. Although this depends on perceptual experiences and on the training of the neuromuscu-lar system during motor development, a dyspraxia may be present on its own or together with perceptual problems (agnosias) in brain-damaged children. Specific teaching, or if dyspraxia is severe, cues for function without confronting the specific dyspraxia are provided by specialist, occupational therapists and specialist teachers.

Specialised perceptual and praxic training (including visuomotor training). This may be needed for many specific problems found amongst children with cerebral palsy with a primary motor impairment. Once again these problems may sometimes be even more disabling than the motor impairment. Referral for special assessment is essential to understand why a child is not progressing with physiotherapy methods. The general perceptual experiences are already included in the motor developmental training. This is not enough. It is also important to recognise that many children do not have these specific problems as perception and praxia are also being trained within the activities of feeding, dressing, washing, bathing, toileting and especially playing. The specialised therapy and education needed is discussed in other publications and advice must be sought from psychologists, teachers in special education, occupational therapists and physiotherapists working with developmental coordination disorder (Ayres 1979; Fisher et al. 1991; Steel 1993; Lee 2004, among others).

Motor function and communication, speech and language

The earliest communication between parent and child is within feeding behaviour. Therefore, the sections on communication and feeding need to be understood together as they are so intimately related. As this book focuses on motor function in cerebral palsy, the sections are only separated for clarity but not to neglect the integration of these functional aspects.

The development of speech and language requires special assessment, suggestions and treatment from speech and language therapists (Levitt & Miller 1973; Latham 1984; Winstock 2005; Stroh et al. 2008). See section ‘Parent–child interaction’ in Chapter 2.

Development of communication – brief summary

Speech and language development is very individual. The following is only a framework for most children:

0–3 months. Differentiated cries, eye-to-eye contact and expresses self with facial expressions and

body movements. Makes sounds during kicking and feeding. Stills to noise. Smiles at parent.

3–6 months. Sounds vary, vowels predominate. Child gives clear signals of likes/dislikes. Anticipates food by opening mouth. Babbling begins, increasing intonations. Watches adult’s lips. Turns to sounds and parent’s voice. Laughs, squeals and annoyed screams. Excited limb motions as social responses.

6–9 months. Lip and tongue sounds. Syllables (ba-ba, da-da) with self-imitation. Actions anticipating being lifted. Uses voice to attract attention. Bounces on laps, showing pleasure and may indicate ‘more’.

9–12 months. Double syllables, first word. Uses gestures especially pointing. Waves goodbye. Turns to sounds that interest him instantaneously. Continues vocalising to make personal contact. Imitates rhythmical sounds with movement. Playful turn-taking with familiar adults.

12–18 months. Understands more than expresses. Follows repeated adult’s simple directions if given with gestures (‘Give me’, ‘No’, ‘Arms up’). Responds to his name, single word and perhaps some meaningful words. Real object labels. Imitates sounds and intonations, develops baby jargon language.

18–24 months. Imitates adult speech (echolalia). Begins to imitate other children. Responds and discriminates sounds, responds to simple commands. Development of meaningful words and two or three word phrases. Has a growing vocabulary. Continues to love listening to stories, enjoys jingles and movements to nursery songs.

2–3 years. Simple short sentences to express self, especially likes/dislikes, many questions and verbal explosion. Gives own name. nursery rhymes, talks to himself during play and is using imaginative play which will increase with complexity after 3 years. Normal stutter, for example ‘m,m,mummy’. Repetition of sounds and words. Unique dialogues.

Practical suggestions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree