CHAPTER 23 Modular Bicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

Modular bicompartmental knee arthroplasty is an effective consideration for patients with bicompartmental disease, when there is reasonable range of knee motion, minimal deformity, and stable ligaments.

Modular bicompartmental knee arthroplasty is an effective consideration for patients with bicompartmental disease, when there is reasonable range of knee motion, minimal deformity, and stable ligaments. Unlike a monolithic femoral component, a modular approach to bicompartmental knee arthroplasty allows independent component sizing and alignment, without having to compromise either.

Unlike a monolithic femoral component, a modular approach to bicompartmental knee arthroplasty allows independent component sizing and alignment, without having to compromise either.Introduction

Isolated unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) and patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA) are effective for localized arthritis; however, arthritis commonly affects both the medial (or lateral) and patellofemoral compartments, and traditionally total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has been performed in those circumstances. While some have suggested that patellofemoral arthritis and symptoms can be ignored when performing UKA,1,2 others have not replicated that approach. Additionally, the presence of grade 3 or 4 chondromalacia in the medial or lateral compartments is a contraindication to PFA when treating patellofemoral arthritis, making TKA the conventional treatment.3

A disruptive evolutionary approach to tissue-sparing partial knee arthroplasty was introduced several years ago in the form of a monolithic bicompartmental knee arthroplasty, which resurfaces the medial and patellofemoral compartments, sparing the cruciate ligaments and lateral compartment.4 While the initial reception to the concept of bicompartmental knee arthroplasty was lukewarm, it is gaining interest and relevance as techniques improve, designs change, and results emerge. Two generic methods of bicompartmental knee arthroplasty are currently available—my preference is a modular approach, utilizing separate and unlinked UKAs and PFAs; the alternative, discussed in other chapters of this book, is either an off-the-shelf or custom monolithic prosthesis with a linked trochlear and unicondylar femoral segment. This chapter discusses the rationale for use of an unlinked modular bicompartmental knee arthroplasty and its clinical results.

Rationale for Bicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

The rationale behind this strategy to knee arthroplasty is twofold. First, a large segment of patients undergoing TKA have isolated bicompartmental arthritis involving the medial (or lateral) and patellofemoral compartments and have no significant deformity, excellent motion, and intact cruciate ligaments. One radiographic study of 470 knees evaluated for osteoarthritis found that 50% had arthritis affecting both the medial and patellofemoral compartments, but sparing the lateral compartment, and that tricompartmental arthritis was rare.5 Often these patients are treated with TKA. While this is highly effective in providing considerable pain relief and survivorship, TKA patients often do not achieve the desired level of function and normalcy.6 This may be related to the altered kinematics of the knee following TKA, which tend to be relatively normal after UKA, PFA, and bicompartmental knee arthroplasty due to the retention of the anterior cruciate ligament and anatomic structures in the other compartments.7–9 Second, a number of knees treated with isolated patellofemoral or unicompartmental tibiofemoral arthroplasty will develop progressive arthritis in an un-resurfaced compartment of the knee over a period of time and are often converted to TKAs rather than adding a partial knee arthroplasty to the degenerated compartment. Staged modular bicompartmental arthroplasty may be a valid treatment method in these situations. However, despite its intuitive, rational philosophy, few data exist regarding how patients may fair if a modular stepwise approach to resurfacing is utilized rather than conversion to TKA in these patients.

Indications for Bicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

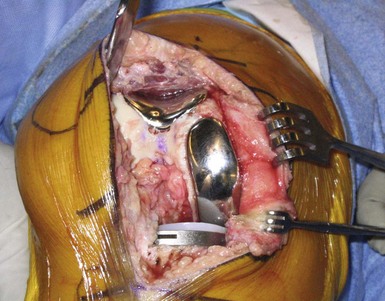

The indications for this procedure are similar to those used for UKA or PFA, with the addition of arthritis or painful chondromalacia in the “second” compartment (Fig. 23–1). Therefore, it can be used for patients with medial or lateral compartment and patellofemoral degenerative joint disease or painful chondromalacia, provided there is full extension (or less than a 5° flexion contracture), “good” range of motion (typically greater than 90° of flexion), minimal deformity, functional cruciate and collateral ligament stability, and an intact and painless “third” compartment. Further details of the indications for isolated unicompartmental and patellofemoral arthroplasty are given in their respective chapters in this book. While some surgeons may prefer to restrict this surgery to patients who are young and active, I have had great success in elderly patients and offer it to appropriate candidates without applying arbitrary age restrictions. Some surgeons have advocated isolated medial unicompartmental arthroplasty with a mobile-bearing implant design for bicompartmental arthritis involving the medial and patellofemoral compartments, in essence disregarding the arthritis and symptoms in the patellofemoral compartment.1,2 Berend et al.1 and Beard et al.2 have found that neither preoperative patellofemoral arthritis nor pain negatively impacts the results of the unicompartmental arthroplasty using a mobile-bearing implant. On the contrary, others have found that failures due to anterior knee pain will predictably occur when resurfacing only the medial compartment of the knee when there is also patellofemoral arthritis. Since the data regarding mobile-bearing knees in bicompartmental arthritis have not been replicated in other series (particularly those using fixed-bearing implants), and the rational explanation for the apparent absence of patellofemoral symptoms is elusive, my preference is to treat patients with bicompartmental arthritis and symptoms involving both the medial (or lateral) and patellofemoral compartments with modular bicompartmental arthroplasty (Figs. 23–2 and 23–3).

Rationale for Unlinked Modular Bicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

With this philosophical approach to bicompartmental resurfacing, the varus-valgus alignment of the component is determined by the apposition of the lateral transitional edge of the trochlear component with the lateral femoral condyle. Given the variability in coronal alignment and morphology of the distal femur, there will be concomitant variability in how the implant can be aligned to ensure that the lateral edge of the trochlear prosthesis is flush with the lateral femoral condyle. This may compromise sizing and alignment of the condylar portion of the prosthesis. Certainly, an analysis of radiographs of the monolithic implant will show variability in the trochlear and condylar orientation relative to the distal femur with some components in varus, others in valgus, and others in neutral alignment relative to the femoral mechanical axis (Fig. 23–4). This malalignment can have detrimental implications for durability and functional outcomes. Except in ideal morphologies of the distal femur, it is rare to have both segments of the prosthesis (i.e., the trochlear and condylar segments) aligned and sized perfectly with a noncustomized monolithic prosthesis. Whether compromise in the alignment or position has deleterious implications on patellar tracking and midterm performance of the implant is not yet known; however, it may explain why one series of 42 monolithic bicompartmental knee arthroplasties reported 12% revisions and 25% anterior knee pain at short-term follow-up.10

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree