Modified Woodward Repair of Sprengel Deformity

J. Richard Bowen

DEFINITION

Sprengel deformity is a congenital anomaly of the shoulder characterized by a high elevation of a hypoplastic scapula and medial rotation of its inferior pole.6, 7, 22 The exact cause of the deformity is unknown.

Associated anomalies include Klippel-Feil syndrome, rib deformities, omovertebral bone formation, muscleanomalies, clavicle hypoplasia, tracheoesophageal fistula, anal stenosis, kidney anomalies, diastematomyelia, and scoliosis.1, 2, 5, 14, 17, 25

ANATOMY

The normal scapula forms in the fifth week of fetal development adjacent to the level of C5 and then descends to the dorsal thoracic area at a level between T2 and T8.

The scapula in Sprengel deformity is abnormally high, has a decreased vertical diameter, and is deformed in shape.

The supraspinous region is rotated anteriorly in a convexity near the shape of the dorsal thorax.

The inferior aspect of the scapula is rotated medially.

The scapula in Sprengel deformity may be attached to the lower cervical vertebrae (usually C6) by an abnormal band of tissue, which may be fibrous, cartilage, or bone (ie, omovertebral bone).25

The musculature of the shoulder girdle may be hypoplastic, absent, or weak.

The trapezius muscle, the levator scapulae muscle, and the rhomboid muscles often are hypoplastic.

The trapezius is the most commonly affected muscle. Other muscle groups that attach to the scapula occasionally are affected.

PATHOGENESIS

The normal scapula develops in the cervical region and then descends to the upper posterior area of the thorax by the end of the third month of fetal development.

Sprengel deformity occurs as a result of interruption of the normal caudal migration of the scapula during fetal development.10

The etiology of Sprengel deformity is unknown, but the following theories have been proposed5, 21, 24:

Cerebrospinal fluid escapes through a “bleb” in the membrane of the roof of the fourth ventricle into the adjacent tissue of the neck to cause malformations.

Heredity (there have been several reports of familial occurrence)

Increased intrauterine pressure

Abnormal articulation of the scapula to the cervical vertebrae and defective musculature formation

NATURAL HISTORY

The Sprengel deformity is present at birth, and the location of the scapula in relation to the neck and thorax remains constant as the child grows.

The abnormal scapula appears to grow proportionally to the growth of the child.

Associated congenital anomalies such as congenital scoliosis may progress, thereby changing the appearance of the deformity.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

At birth, the shoulder with a Sprengel deformity appears to be displaced upward and forward.

In unilateral cases, shoulder asymmetry is evident.

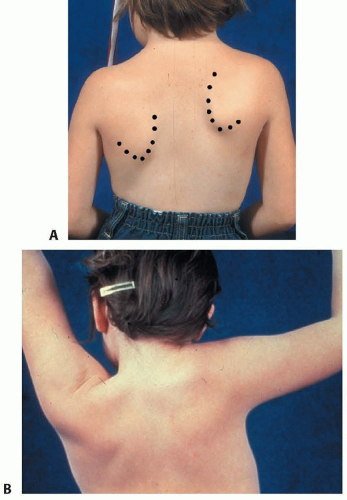

The left scapula is involved more commonly than the right (FIG 1A).

In bilateral cases, both shoulders appear to be high, and the neck may appear thick and short.

The scapula may be tilted upward.

Motion of the shoulder is reduced in abduction and elevation (FIG 1B).

Muscle weakness or hypoplasia can be observed in the shoulder area.

Torticollis may be present.

Scoliosis and kyphosis as well as deformities of the chest from rib anomalies may be observed.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

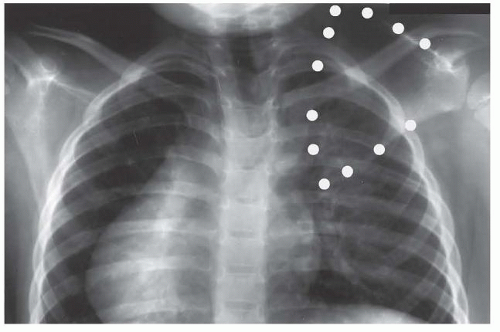

Radiographs of the shoulder and neck show the bone deformities (FIG 2).

Sonography of the spinal cord is helpful in infants younger than about 4 months of age who have congenital spine anomalies.

Sonography can be performed through the cartilage of the lamina and spinous process, but after about 4 to 5 months of age, ossification blocks the views.

Congenital spine anomalies have a high association with intraspinal abnormalities.

Sonography of the kidneys is helpful in cases associated with congenital spine anomalies.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is extremely helpful for evaluating muscle and soft tissue development.

Computed tomography (CT) (with three-dimensional [3-D] reconstruction) is helpful to define the extent of bone deformity. CT provides excellent visualization of the omoverte-bral structure.

Both still and video photography are helpful to record pre- and postoperative appearance and to document function.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

In infants and young children, passive and active stretching exercises may be performed daily to maintain motion of the shoulder.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT