Microfracture Chondroplasty

J. Richard Steadman

William G. Rodkey

DEFINITION

Chondral defects in the knee are common.

The lesions may be partial or full thickness (FIG 1), through all layers of the articular cartilage down to the level of the subchondral bone.

Chondral defects may be acute or chronic.

ANATOMY

The articular cartilage of the knee is 2 to 4 mm thick, depending on the location within the joint.

The articular cartilage is an avascular tissue that is devoid of nerves and lymphatics.

FIG 1 • A. A full-thickness chondral defect through all layers of the articular cartilage is outlined (arrows). B. A full-thickness chondral lesion.

Relatively few cells (chondrocytes) are present in the abundant extracellular matrix.

These factors are critical in the lack of a spontaneous or naturally occurring repair response after injury to articular cartilage.

PATHOGENESIS

The shearing forces of the femur on the tibia as a single event may result in trauma to the articular cartilage (FIG 2), causing the cartilage to fracture, lacerate, and separate from the underlying subchondral bone or separate with a piece of the subchondral bone.

Chronic repetitive loading in excess of normal physiologic levels also may result in fatigue and failure of the chondral surface.

Single events usually occur in younger patients, whereas chronic degenerative lesions are seen more commonly in persons of middle age and older.5,6,7,8,9,10

Repetitive impacts can cause cartilage swelling, an increase in collagen fiber diameter, and an alteration in the relation between collagen and proteoglycans.

NATURAL HISTORY

Articular cartilage defects that extend from full thickness to subchondral bone rarely heal without intervention.5,6,7,8,9,10

Some patients may not develop clinically significant problems from acute full-thickness chondral defects, but most eventually suffer from degenerative changes that can be debilitating.

Acute events may not result in full-thickness cartilage loss but, rather, may start a degenerative cascade that can lead to chronic full-thickness loss.

The degenerative cascade typically includes early softening and fibrillation (grade I); fissures and cracks in the surface of the cartilage (grade II); severe fissures and cracks with a “crab meat” appearance (grade III); and, finally, exposure of the subchondral bone (grade IV).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The physical diagnosis can be difficult to establish, especially if the chondral defect is isolated.

Chondral lesions can be located on the joint surfaces of the femur, tibia, or patella.

Point tenderness over a femoral condyle or tibial plateau is a useful finding but is not diagnostic.

If compression of the patella elicits pain, a patellar or trochlear lesion may be indicated.

Joint effusion may be present, but it is not a consistent finding.

Catching or clicking may be present, especially if there is an elevated flap of cartilage.

Restricted range of motion (ROM) can be associated with many pathologic conditions of the knee, but the ROM should be documented as a baseline prior to any treatment.

Physical examinations should be performed as follows:

The patella is palpated in superior-inferior and mediallateral directions for evidence of effusion. About 50% of patients with chondral defects have an effusion.

The Lachman test is used to rule out ligamentous instability by applying anterior force to the tibia with the knee in 20 to 30 degrees of flexion.

The thumb and index finger are used to place digital pressure over all geographic areas of the knee to detect point tenderness; this finding is useful but is not in itself diagnostic.

A palpable or audible pop in combination with pain is considered a positive result to the McMurray test, indicating a meniscus lesion rather than a chondral lesion.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

For diagnostic imaging, angular deformity and joint space narrowing are assessed using long-standing radiographs.

Two methods for radiographic measurement of the biomechanical alignment of the weight-bearing axis of the knee are used in our facility:

The angle between the femur and tibia on anteriorposterior (AP) views obtained with the patient standing

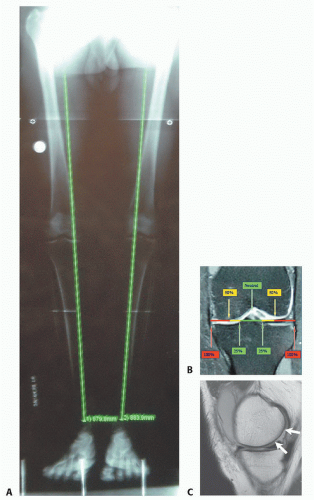

The weight-bearing mechanical axis drawn from the center of the femoral head to the center of the tibiotarsal joint on long (51 inches/130 cm) standing radiographs (FIG 3A)

If the angle drawn between the tibia and femur shows more than 5 degrees of varus or valgus compared with the normal knee, this amount of axial malalignment would be a relative contraindication for microfracture.

We rely most often on the mechanical axis. It is preferable for the mechanical axis weight-bearing line to be in the central quarter of the tibial plateau of either the medial or lateral compartment.

If the mechanical axis weight-bearing line falls outside the quarter of the plateaus closest to the center (FIG 3B), either medial or lateral, this weight-bearing shift also would be a relative contraindication if left uncorrected. In such cases, a realignment procedure should be included as a part of the overall treatment regimen.

Standard AP, lateral, and weight-bearing radiographic views with knees flexed to 30 to 45 degrees also are obtained.

3.0T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which uses newer diagnostic sequences specific for articular cartilage, is crucial to our diagnostic workup of patients with suspected chondral lesions (FIG 3C).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Meniscus tear

Loose bodies

Attached chondral flap

Symptomatic plica

Synovitis

Chondral bruising, with or without subchondral edema

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Patients with acute chondral injuries are treated as soon as practical after the diagnosis is made, especially if the knee is being treated concurrently for meniscus or anterior cruciate ligament pathology.

Patients with chronic or degenerative chondral lesions are often treated nonoperatively (conservatively) for at least 12 weeks after a suspected chondral lesion is diagnosed clinically.

This treatment regimen includes activity modification, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, viscosupplement injections, and possibly dietary supplements that may have cartilage-stimulating properties.

If nonoperative treatment is not successful, then surgical treatment is considered.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Microfracture initially was designed for patients with posttraumatic articular cartilage lesions of the knee that had progressed to full-thickness chondral defects.

The microfracture technique still is most commonly indicated for full-thickness loss of articular cartilage in either a weight-bearing area between the femur and tibia or an area of contact between the patella and the trochlear groove.

Unstable cartilage that overlies the subchondral bone also is an indication for microfracture (FIG 4).

If a partial-thickness lesion is probed and the cartilage simply scrapes off down to bone, we consider this a fullthickness lesion.

Degenerative joint disease in a knee that has proper axial alignment is another common indication for microfracture.

FIG 5 • For the definitive procedure, the distal portion of the table is lowered so that the foot is off the table and the knee is flexed 90 degrees.

These lesions all involve loss of articular cartilage at the bone-cartilage interface.

Preoperative Planning

All imaging studies are reviewed.

MRI scans are re-reviewed for presence of concomitant pathology.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree