Chapter 10 Mental Health

Introduction

• As a student or newly qualified physiotherapist you may be expected to treat adults of working age or older adults in acute mental health wards, community mental health teams or outpatient settings such as gyms.

• Although it is possible that you will also work with adolescent patients or service users in eating disorder or forensic units, in these areas it is much more likely that you would be working under the immediate direction of a senior practitioner.

• For this reason the treatment plans considered in this chapter relate to referrals for assessment and consequent treatment of an adult with poor general well-being, an older adult with mobility problems and an inpatient in an acute stage of anxiety and depression experiencing musculoskeletal disorder.

• As with all specialities the holistic nature of treatment demands that it be part of a multidisciplinary approach which includes the patient/service user and where appropriate the carer/s.

• All aspects of the service user’s life may affect outcomes, including social, environmental factors, alongside the psychomotor signs and symptoms, and so all aspects should therefore inform the approach and delivery of treatment.

• Treatment plans will be based on assessment and driven by goals chosen, or at very least agreed, by the service user (in the case of later-stage dementia the carer may be the person leading the goal setting).

• Goals may be long or short term and should mirror or dovetail with the psychological and social goals, which may already have been set between the service user and others in the team.

Mental Health Act and sectioning

• Patients may be in hospital voluntarily or they may be detained under a section of the Mental Health Act for their own or other people’s safety. Detention is often referred to as ‘Sectioning’ which refers to a particular section of the Mental Health Act (HM Government 2007). A very specific process must be adhered to in sectioning someone and there are reviews and processes which must be followed including the right of appeal for the person.

• Whilst in hospital a patient may be cared for at a specific level of observation related to the assessed risk. Risks may be of absconding, self-harm, harm to others, lack of self care. The level of observation 1–3 refers to the frequency of observation and also the proximity of the observer, for instance level 3, 15-minute observations mean that a member of staff would know where a patient was and what they were doing every 15 minutes but they could view this from a distance, ‘level 1 observation constant observations’ would mean a member of staff would be within arm’s length constantly.

• Consider what this might feel like, especially if one already feels paranoid. The status of the patient will affect the treatment options you have. For instance if a walk is part of your treatment plan then a sectioned patient will have to have ground leave agreed by the responsible medical officer. In forensic settings it is likely that the majority of patients will be on section and will need ground leave which may have to be very specific, e.g. 30 minutes, within the grounds with two escorts between the hours of 10.00 and 12.00; or one hour to walk to and from shops with one escort. For some patients who are under a forensic section of the Mental Health Act permission has to be agreed by the Home Office.

Promotion of well-being

• It falls within the remit of the physiotherapist in mental health to promote well-being, which may encompass weight management plus advice concerning diet, smoking, use of alcohol and physical activity.

• Much will depend upon the resources available to you and the awareness of the team.

• Thus referral to the dietician, smoking cessation adviser or GP for review of medication, may happen via other members of the Community Mental Health team but if referral to the physiotherapist is the first action taken then the physiotherapist needs the knowledge and skills to refer on or to signpost to the most appropriate service.

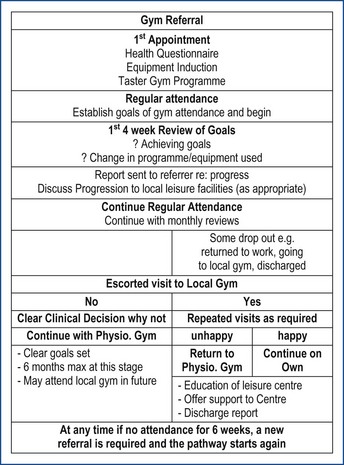

• A referral is likely to come from the care co-ordinator or possibly self referral from the service user and to be for increase in fitness and reduction of weight.

• Following musculoskeletal assessment and treatment of any specific disorders the goals for general well-being should be set.

Adults with enduring mental health disorder

• For patients with long-term and enduring mental disorder lack of motivation will be, and will have been, a major barrier to fitness. If the service user has been on psychotropic medication for many years then weight gain will have occurred but the lack of activity and diet are likely to be key factors in lack of well-being.

• Patients with long-term and enduring mental disorder are four times more likely to die of cardiorespiratory diseases than are the general population (Phelan et al 2001).

• The body of evidence linking diet with mental health is growing at a rapid pace. As well as its impact on feelings of mood and general well-being, the evidence demonstrates diet contributes to the development, prevention and management of specific mental health problems (Mental Health Foundation 2007).

• Musculoskeletal assessment should have included checking joint range, muscle power, reported pain but should focus on function.

• Questions about what the service user can and can’t do physically and what if anything he wants to do about it should be the basis for intervention.

• Specific measurement of body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference may be appropriate on initial assessment or may cause distress and need to be addressed at subsequent appointments.

• The expertise of the physiotherapist should be initially employed to assess and treat any musculoskeletal disorders such as painful joints or injured muscles in preparation for a physical activity programme.

• In many mental health settings technical instructors (TIs), with a background in sport and physical fitness, work with the physiotherapists and can be very effective in delivering the activity plan when it has been devised.

• In some mental health gyms the TIs have a lead role and physiotherapists are involved only if there is a specific need due to injury or physical disorder.

• For patients with low motivation self-reporting questionnaires do not always provide full histories or clear progression lines. An interview screening tool with review will be more useful and can be administered by either the physiotherapist or the technical instructor.

• In this case the physiotherapy student or novice physiotherapist may learn from the experienced non qualified staff member the best way to approach a service user.

• Reviews rating to the baseline screening should take place at regular intervals being sure to involve the service user in a way which is meaningful to them.

Suggested treatment goals

• The short-term goals for a person with low motivation and possible fatigue due to lack of activity must initially be about identifying need and encouraging regular attendance.

• This can be facilitated by the use of treatment contracts where the service user agrees both goals and ways of achieving the goals. Contracts provide a structure to describe the methods to be used and this can help the physiotherapist devise relevant and interesting programmes for the service user.

• Motivational interviewing (MI) skills are a useful technique in these circumstances as they encourage the service user to direct the change. Originally used for counselling ‘problem drinkers’ the interviewing technique produces a relationship which reflects partnership rather than following an expert–recipient model (Rollnick and Miller, 1995).

The question of weight

• A service user may be morbidly obese to the point where even the effort of rising to standing is exhausting.

• Alternatively the service user may have been neglecting to eat regularly and have a low BMI which may cause concern in terms of sufficient calorific intake to support exercise.

• If the decision is to provide a physical activity programme then weight must be considered. Each person’s needs should be considered individually but a BMI below about 18.5 would militate against anything other than very gentle exercise and stretching.

• All multigym machines will have a specific weight limit and the service user’s weight may exceed this. Always check before suggesting use of exercise machines.

• For extremes of weight levels some useful forms of exercise are:

• A slow start, mild to moderate level exercise should be planned first and explained carefully to the service user as part of their treatment plan and goals.

• Progression from individual forms of exercise should happen at a pace which encourages the service user to continue with activity and /or exercise, until it becomes part of that person’s habit.

• At this point in the treatment new musculoskeletal disorders may become apparent and they should be assessed and treated as part of the total treatment pathway.

• However the physiotherapist should be ready for intermittent attendance, relapse in illness or poor concordance with diet regimens all of which will interfere with goal time lines.

• Patience and innovation in treatment intervention can make a long process more successful.

Specific outcomes

• Measurement such as BMI, waist circumference can be used to show weight reduction.

• To evaluate endurance the measures could include

• A subjective measure fulfils the basis of our treatment to give back to the patient some feeling of control over their body and what they are capable of doing with it.

• The service user is invested with the means of regulating how hard they are working whilst at the same time the therapist has some means to demonstrate improvement.

• A regular visual analogue scale with fearful or unhappy at level one and very confident or happy at level 6 can be applied to any of the activities agreed as ways to reach goals or functions which were identified as difficult.

• It cannot be emphasised enough that the baseline for all of the strength and stamina measures is likely to be very low compared to expected norms, so improvement no matter how small will be a health gain.

• The gain in fitness from completely sedentary lifestyle to a moderately active lifestyle occurs at a much faster rate than gains in moderately active to a very active lifestyle.

• Completion of treatment should take the service user to independent (or support worker aided), use of community facilities in leisure centres, swimming pools, walking groups. The student or novice physiotherapist may not be with the service user long enough to reach this point, but they will have put them on that path.

• Although we may be the physical expert it is well to remember that in reducing pain, increasing activity and supporting personal achievement will affect the patient’s mental well-being and contribute to raising mood, structuring the day and giving an improved sense of mastery.

• In this way the physiotherapist is truly working holistically.

Table 10.1 The Borg CR10 exertion scale

| 0 | Nothing at all | ‘Number 1’ |

| 0.3 | ||

| 0.5 | Extremely weak | Just noticeable |

| 0.7 | ||

| 1 | Very weak | |

| 1.5 | ||

| 2 | Weak | Light |

| 2.5 | ||

| 3 | Moderate | |

| 4 | ||

| 5 | Strong | |

| 6 | ||

| 7 | ||

| 8 | ||

| 9 | ||

| 10 | Extremely strong | ‘Strongest 1’ |

| 11 | ||

| Absolute maximum | Highest possible |

Older adult mobility in dementia

• For the older adult patient mobility is the most frequent cause of referral to physiotherapy.

• Physiotherapists in many specialties including the ‘core’ areas of musculoskeletal, neurological and cardiorespiratory will encounter patients with dementia and with an aging population this will become more common.

• The following treatment suggestions are focussed on the approach and possible treatment goals for a patient with moderate dementing changes.

• The classic work of Rosemary Oddy initially written for carers and relatives is a useful resource when treating patients with dementia (Oddy 1998).

• In early stages of dementia the difficulty may be poor mobility, however in later stages the referral to physiotherapy may be to advise on lowering the level of activity.

Treatment goals

• Following assessment the treatment plan will always include achieving safe movement in functional situations, thus, moving in bed, getting in and out of bed, sitting to standing and reverse, stabilising base to allow reaching.

• The other essential is to provide advice to the team and relatives or carers regarding safe management of mobility for the patient.

Aspects of dementia which will affect treatment

• All the impairments which may accompany dementia will not necessarily be seen in one person, but there are a number of symptoms which will affect both the approach to and the success of treatment.

Memory

• Patients with early-stage dementia may find mobility difficult because they begin to go somewhere and then forget why and where they are walking, or they forget that they have difficulty moving which produces a severe falls risk.

• In later stages memory may be so poor that instructions are forgotten almost immediately after they are heard.

Cognition (thought processing)

• Processing instructions becomes difficult and can prove impossible if too complicated.

• Usually when an instruction is given the response is fairly immediate and for functional activities the movement almost automatic.

• For the dementing patient a simple instruction such as stand up may not happen automatically and in trying to think about it the patient can become frustrated.

Orientation

• The ability to recognise time and place may be lost and a person may be convinced that they are somewhere and in some age other than where they are.

• Very often patients will have a clear reason why they cannot come with you or get out of bed or why they must leave the ward, e.g. ‘I am waiting for my son’ or ‘I have to get home to feed the dog and the bus leaves in 10 minutes’.

• It is therefore important to know something of their history and consider the likelihood of the statement.

• Positional orientation may also be affected and a patient may become distressed if moved too quickly from one position to another so allowing adequate time as discussed previously is of the essence.

Emotional affect

• Depression often precedes or appears alongside dementia and this will have an affect on motivation which may already be low due to the cerebral change associated with dementia.

• Anxiety and fear are common symptoms.

• The anxiety may be specific or global resting on any thought which appears.

• Fear due to reduction in ability to make sense of the environment or to persecutory thoughts may be compounded by a specific fear of falling.

Treatment approach

• The approach is derived first from the attitude of the student or novice physiotherapist who should have a positive attitude and be well motivated; be sympathetic to the individual’s difficulties recognising that dementia will affect different people in different ways and ensure that the patient is treated with dignity and respect.

• The key is to plan for success whilst using your skills to make movement enjoyable and including the team, carer and relatives in the plan.

Specific strategies

• Effective communication is essential to influence the different aspects of a patient presenting with dementia.

• Communication techniques comprise of verbal and non-verbal strategies including:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree