5 Medical management of arthritis

Cases relevant to this chapter

20, 26–27, 68, 70, 72–73, 75–77, 79–87, 90–91, 93–94, 96–97

Essential facts

1. Pain is an important feature of musculoskeletal problems and adequate pain relief is essential.

2. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) control the symptoms of arthritis but they can induce gastrointestinal bleeding, erosion and ulceration as well as renal and cardiovascular disease.

3. Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are usually effective singly or in combination and should be used as early as possible.

4. DMARDs are all capable of toxicity and their use must be monitored carefully.

5. Biologic therapy is an important advance in managing resistant cases of inflammatory joint disease.

6. Steroids have a short-term role in managing rheumatoid arthritis but play a more important long-term role in the management of other autoimmune rheumatic diseases, often combined with other immunosuppressive agents, whilst waiting for a DMARD to become effective.

Analgesics

Practical use of analgesics

Simple analgesics can be used in all patients with inflammatory arthritis to control pain (Table 5.1); they are an adjunct to other therapy. The available drugs include paracetamol, weak and strong opioids, tramadol, and combinations of paracetamol and a weak opioid. There is some evidence from clinical trials that analgesics reduce pain in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but the amount of data is very limited. However, almost all rheumatologists recommend using them.

Table 5.1 An analgesic ladder for arthritis

| Step | Pain Level | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| One | Mild | Paracetamol |

| Two | Moderate | Paracetamol plus mild opioid or opioid-like drug (e.g. codeine or tramadol) |

| Three | Severe | Paracetamol plus stronger opioid (e.g. dihydrocodeine or morphine) |

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Conventional nsaids

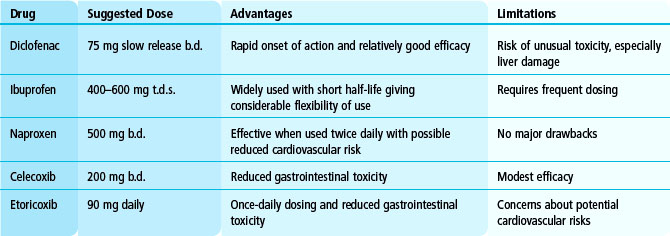

Although there are many NSAIDs, most specialists use only a few. Commonly used NSAIDs are shown in Table 5.2. NSAIDs reduce pain, joint tenderness and the duration of early morning stiffness. They have little impact on systemic effects of joint inflammation and do not reduce the increased ESR of active RA.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree