Medial Approach for Open Reduction of a Developmentally Dislocated Hip

Lori A. Karol

Jeffrey E. Martus

DEFINITION

Developmental dislocation of the hip (DDH) occurs in 1.5 babies per 1000 live births. When diagnosed in the newborn period, closed treatment with the Pavlik harness is successful in 95% of dysplastic hips and up to 80% of dislocated hips.

Closed reduction is indicated when Pavlik harness treatment has failed and when presentation for treatment is delayed past 6 months of age.

Open reduction is reserved for babies in whom closed reduction either is unobtainable or lacks stability or for those who are diagnosed with a dislocated hip later than 18 to 24 months of age.16

The medial approach for open reduction is used most frequently in the young baby 12 months of age or less in whom an attempted closed reduction under anesthesia has been unsuccessful.

ANATOMY

Reduction of a dislocated hip can be impeded by the following:

The iliopsoas tendon, which is tautly stretched across the inferior capsule owing to the displacement of the femoral head

The inferomedial hip capsule, which becomes constricted

The transverse acetabular ligament, which spans the inferior aspect of the horseshoe of the acetabulum and prevents inferomedial seating of the femoral head in the acetabulum

The pulvinar, which is fibrofatty tissue occupying the cavity of the true acetabulum

The acetabular labrum, which can be infolded and serve as a doorstop blocking a deep and medial reduction

Anatomic landmarks for the medial approach are as follows:

The adductor longus tendon originating on the pubis

The pectineus, lying anterior to the adductor brevis (which is deep to the adductor longus)

The femoral artery, vein, and nerve, which are located as a bundle anterior to the pectineus muscle

The medial femoral circumflex artery, which lies in the interval between the pectineus and the femoral neurovascular bundle and is important for the circulation of the ossific nucleus of the proximal femur

PATHOGENESIS

DDH is more common in female babies and is linked with breech presentation, oligohydramnios, and first-born children.

DDH is associated with congenital knee hyperextension and may be more likely in babies with torticollis, clubfoot, and metatarsus adductus.

A positive family history is present in a minority of babies with DDH and most likely represents familial hyperlaxity.

Idiopathic DDH must be differentiated from the teratologic hip dislocation seen in infants with such disorders as arthrogryposis and Larsen syndrome.

NATURAL HISTORY

Although research has shown that mild dysplasia, seen on ultrasound imaging of the newborn hip, often resolves spontaneously without treatment, there is significant risk that babies with dislocatable or dislocated hips will progress from unstable hips to fixed dislocations in the absence of treatment.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The physical examination methods are summarized in the following text. It is very important that the child is relaxed and quiet during the examination.

Limited abduction during range-of-motion testing may signify a fixed dislocation and merits imaging. Abduction can be symmetric in bilateral dislocations.

The patient is examined for the Galeazzi sign. Asymmetry is abnormal and may indicate a hip dislocation or a congenital short femur. The apparent femoral lengths will be equal in bilateral dislocations.

Extra thigh folds may be present in unilateral DDH, but thigh fold asymmetry is usually nonspecific.

The child is examined for the Ortolani sign. A positive sign represents the reduction of a dislocated hip. It is usually present in the newborn with DDH but disappears as the dislocation becomes fixed.

A positive Barlow sign represents the ability for a reduced hip to be dislocated because of instability. It disappears as a fixed dislocation develops.

In addition to a complete examination of each hip, the knees, feet, and upper extremities should be examined for contractures to rule out a teratologic dislocation.

The spine should be inspected for signs of dysraphism, which may result in a hip dislocation due to muscle imbalance.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

In infants younger than 4 months of age, ultrasound of the hip is the preferred imaging study.

The femoral head, acetabulum, and triradiate cartilage can be identified.

The absence of coverage of the femoral head by the bony acetabulum is seen in the dislocated hip, which appears lateralized relative to the pelvis.

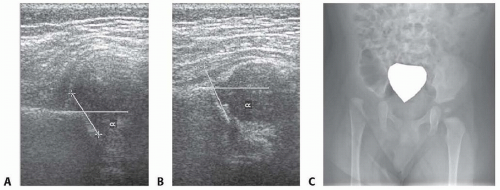

The alpha angle, which represents the slope of the bony acetabulum, is decreased (normal is more than 60 degrees), and the beta angle, which represents the cartilaginous acetabulum, is increased (normal is <55 degrees) in babies with hip dysplasia and hip dislocation (FIG 1A,B).

In infants 4 months of age and older, an anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiograph is diagnostic (FIG 1C).

The line of Shenton, drawn along the inferomedial aspect of the proximal femur and the superior aspect of the obturator foramen, is disrupted.

The ossific nucleus may be smaller than the contralateral side or absent altogether.

The medial proximal femoral metaphysis lies lateral to the Perkins line (drawn vertically from the lateral aspect of the bony acetabulum).

The acetabular index, which is the angle subtended by the Hilgenreiner line (a horizontal line drawn through the triradiate cartilages), and a line drawn along the bony acetabulum, is increased.

A pseudoacetabulum proximal and lateral to the true acetabulum may be present.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Teratologic hip dislocation (ie, arthrogryposis)

Neuromuscular dislocation (ie, spina bifida)

Congenital short femur

Coxa vara

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The Pavlik harness is the treatment of choice for infants with hip dysplasia or instability from birth to age 6 months.

The Pavlik harness is less successful in patients with fixed dislocations but may be attempted for a period not to exceed 4 weeks, following which a reduction must be documented by either sonogram or radiograph.

There is no role for nonoperative management of an otherwise healthy baby 6 months of age or older with a fixed hip dislocation.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical management can be delayed in the very young infant until the baby reaches sufficient size for a safe anesthetic and effective cast immobilization. We favor proceeding with surgical reduction (closed or open) at the age of 6 months in the healthy baby.

The importance of delaying surgery until the presence of ossification within the femoral head remains controversial.11 Although some studies report an increased incidence of avascular necrosis when the ossific nucleus is absent, others report an increased number of surgical procedures in children in whom reduction is delayed. We favor proceeding with reduction rather than waiting for ossification.7

Preoperative Planning

Traction may be used to increase the likelihood of a successful closed reduction, although current trends in the United States show a declining use of preoperative traction.

Positioning

The child is positioned supine on a radiolucent operating table.

The perineum is isolated with adhesive tape.

Surgical drapes are sutured in place to allow free movement of the extremity.

Towel clips should be avoided around the groin, as they interfere with fluoroscopic visualization of the hip.

Approach

The medial approach to the dislocated hip is best suited to infants younger than 12 months of age, but it has been used by other authors successfully in infants up to 24 months of age.

The medial approach described by Ludloff8 accesses the hip in the interval between the pectineus and the adductor brevis.

We favor the anteromedial approach described by Weinstein13 and Weinstein and Ponseti,14 which exposes the hip between the femoral neurovascular bundle anteriorly and the pectineus muscle posteriorly. This interval allows for more direct visualization of the hip capsule and the medial femoral circumflex artery.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Incision and Initial Dissection

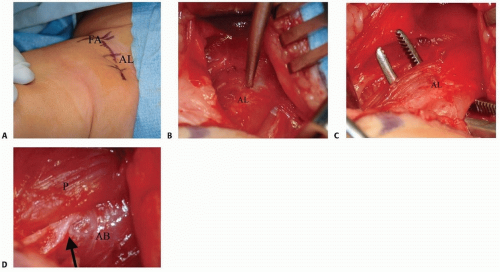

With the hip flexed and abducted, a transverse incision is made just lateral to the groin crease, centered over the palpable adductor longus tendon (TECH FIG 1A).

The fascia overlying the adductor musculature is opened (TECH FIG 1B).

The adductor longus tendon is isolated and divided (TECH FIG 1C). The tendon can be dissected free from the underlying adductor brevis with two blunt retractors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree