7 Massage techniques

Lubricants (massage media)

Points for massage with a lubricant

• Friction on the skin is reduced;

• Fragile skin is protected from being stretched;

• Very hairy skin is protected from being pulled;

• Some oils (e.g. wheatgerm, olive) are said to aid skin nutrition;

• Perspiration can be absorbed by a powder lubricant;

• The gliding effect of some massage manipulations is enhanced;

• Perfumed oil has a beneficial psychological effect on the patient;

• Essential oils can be selected for their therapeutic properties; and

• Lubricants make it easier to perform a comfortable massage.

Points for massage without a lubricant

• Massage can be applied more deeply in the tissues;

• Oil is messy to use and easily spilled;

• A lubricant may cause an allergic reaction;

• Lubricants create an increased risk of infection;

• The tissues are more easily palpated;

• The massage can be more stimulating;

• Tissues are more easily manipulated if they are not slippery;

• Commercial massage oils are over-priced and highly scented; and

Condition of the skin

On hairy, fragile or scaly skin a lubricant will aid patient comfort and prevent irritation.

Possibility of allergic reactions

Some people are allergic to nuts and will have an anaphylactic reaction (which causes shock, an acute fall in blood pressure, laryngeal oedema and bronchospasm, and can be fatal) if they are exposed to oil derived from nuts. Peanuts are the most common allergen: about 1 in 500 of the population is affected (Demain 1996). This type of allergy is becoming more common and exists whereby very young children are sensitised (Ewan 1996). Arachis oil is derived from peanuts and many commercial massage lotions use a nut oil, such as almond or hazel, in their preparation. The therapist should always question the patient concerning allergies before using any lubricant and be fully aware of the constituents of any lubricant she has not prepared herself.

Categories of lubricant

Lubricants of mineral origin

Baby oil, petroleum jelly, liquid paraffin, French chalk, talc, cold cream.

Comments

Oils of vegetable origin are generally the most pleasant to use and are suitable as a carrier with essential oils. It has been found to penetrate transcutaneously in neonates (Solanki 2005), whereas the molecular structure suggests that it is unlikely to penetrate this deeply in adults (Zatz 1993). Mineral oil does not penetrate the skin well and is therefore unsuitable for carrying volatile oils into the tissues. The lack of this property does, however, convey an advantage for general massage purposes, as it tends to stay on the surface of the skin and less is needed. There is some controversy concerning the use of mineral oil. Taken internally in large quantities it can interfere with the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, but there is no evidence to suggest that it is detrimental when used as a massage lubricant (Skiba 1993). Some vegetable oils are more viscous than others (e.g. olive, wheatgerm) and should be added in small quantities to a lighter oil. Vegetable oils can become rancid; keeping supplies refrigerated in a well-sealed container slows this process, as does the addition of 5% wheatgerm oil, which has antioxidant properties. A therapist with sweaty palms may find that powder is a more suitable lubricant as it absorbs some of the moisture. A fine non-perfumed talc has traditionally been a useful addition to the therapist’s equipment; some patients prefer it to oil and it does not degrade. Consent should be obtained from the client before using talc and great care should be taken to ensure it does not invade the atmosphere and that it cannot be inhaled by either the client or the therapist.

Essential oils

Aromatherapy is the name given to application of essential oils, which are the oils that provide the scent and/or flavour to flowers, fruit and herbs. They have been extracted from the plants and used for this purpose for thousands of years (Tisserand 1994), as herbal medicines, inhalations or compresses. Pure oils can be extracted from the leaves, flowers or seeds of plants and used for specific therapeutic purposes. Many have a pleasant smell which produces a psychological effect, a feeling of well being. Inhalation also ensures that they enter the bloodstream quickly through the highly vascular lung and respiratory tract fields; a popular method of inhalation entails heating the oils in an aromatherapy burner. Alternatively, they may be added to a warm bath for inhalation and skin absorption. They can therefore be self-administered, used simply to create a pleasant smell and atmosphere in a room, or can be skilfully prescribed and blended by an aromatherapist. Detailed discussion of each oil, sufficient to guide professional aromatherapy prescription, is beyond the scope of this book. However, the principles are described here to a sufficient depth to assist massage therapists to select a limited number of oils for safe use as a therapeutic or pleasantly scented medium.

Massage is a particularly popular way of applying essential oils, and results in a slow penetration. The oils are dissolved in a carrier oil and used as the medium for massage, allowing the effects of the oils to combine with the therapeutic effects of the massage. Relaxation massage should be used (see, for example, the one described in Chapter 10). As with any therapeutic substance that enters the body, dangers and side effects may be present and anyone using these oils for any purpose should be aware of them. This applies particularly to a therapist using oils in health care settings where clients may have a variety of health problems. Unfortunately, research into the effects of the oils is patchy and knowledge is based predominantly on oral tradition. Where research has been undertaken, it has often focused on the main chemical constituents of the oils, so pure oils should be used in which the constituents are known. Good quality oils from professional suppliers are the purest, and inexpensive ones should be avoided. Air, heat and light can cause degradation of oils. This results in a changed chemical composition which may be less effective or more toxic; therefore oils should be kept in a cool, dark environment and not kept for longer than 6 months once opened unless in a fridge. This safety advice is important as degradation and oxidation may make the oils more likely to become carcinogenic, although the transfer of research conducted on rats to humans is not straightforward (Tisserand 1996).

Any therapy which has been used throughout history becomes refined through experience and often the knowledge surrounding its use is accurate. Present-day researchers are attempting to deepen this knowledge of essential oils in the light of current scientific methods by isolating specific constituents of the oils and testing their effects. Albert-Puleo (1979) reviewed the literature concerning the oestrogenic properties of fennel and anise, as identified by numerous animal experiments conducted in the 1930s and 1940s. He suggested that the oestrogenic active ingredients are anethole polymers. Work by Taylor (1964) has shown fennel to have low toxicity and no demonstrable carcinogenicity. Thyme (Thymus capitatus) has been found to have strong fungitoxic properties (Arras & Usai 2001).

Other researchers have attempted to define the effects of individual oils and isolate their mechanism of action. An example is the work by Aqel (1991) in which he applied oil of rosemary to rabbit and guinea-pig tracheal muscle samples. The oil inhibited muscular contractions induced by histamine and acetylcholine. Aqel suggested that the oil is a calcium modulator. Hills and Aaranson (1991) agreed with this suggestion, following similar work on the effects of peppermint oil on smooth muscle. Oil of orange diffused through a dental waiting room was found to have a relaxant effect (Lehrner et al 2000). Cooke and Ernst (2000) conducted a systematic review and concluded that aromatherapy massage has a mild, transient anxiolytic effect, useful for relaxation but not strong enough for the treatment of anxiety. Anderson et al (2000) found that tactile contact between mother and child in the form of massage improved childhood ectopic eczema but that adding essential oils was not more beneficial. A number of studies into the clinical effects of lavender oil in, amongst others, depression (Akhondzadeh et al 2003), postpartum perineal discomfort (Dale & Cornwell 1994), during radiotherapy (Graham et al 2003), anxiety and self-esteem (Rho et al 2006) and dementia (Snow et al 2004) have been conducted. The evidence remains unclear in all except for anxiety. Tea tree oil has attracted research interest as laboratory studies have found antimicrobial properties (Christoph et al 2000). Human studies, mostly on fungal infections, remain inconclusive (Arweiler et al 2000, Martin & Ernst 2004, Satchell et al 2002).

There is concern about the possibility of adverse effects of oils. Research in this area has often been conducted on animals using huge dosages of the oil, so transferability of findings to humans is difficult. Elliot (1993) reported a case of tea-tree oil poisoning, but suggested it may have been an allergic reaction. There is a growing body of literature on this topic (such as Prashar et al 2004) and this should be studied in detail by anyone qualified to prescribe essential oils for massage. This is also the case for interactions of essential oils with drugs. This does, however, highlight the fact that ingestion of these oils can carry some risk, the extent of which is unknown where there has been insufficient research. Studies into microbiological effects are easiest to conduct under controlled, scientifically valid conditions. Bassett et al (1990) found tea-tree oil to be as effective as 5% benzoyl peroxide in the treatment of acne, with fewer side effects. Carson and Riley (1994) found that terpinen-4-ol was the main antimicrobial component of tea-tree oil. It was tested against 12 organisms, including Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans and Lactobacillus acidophilus, and only one of the 12 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) was found to be resistant to the oil. A detailed literature review of essential oils will not be undertaken here, but the clinically based studies are often inconclusive, conducted on animals and not readily transferable to humans. Caution is therefore needed and external application is safer than internal use. Aromatherapists should understand as much as possible about the oils they prescribe, and attempts are being made to examine and address safety issues (Tisserand & Balacs 1995).

Use of essential oils in massage

Choice and prescription of oils can be interesting. The principles of perfumery and medicine are used: asking what types of scents the patient prefers and blending from a base note (fixative), middle note (relates to bodily functions, with a longer lasting scent) and top note (volatile and stimulatory, often smelled immediately the top is removed from a bottle). It is possible to buy an essential oil preparation or a massage oil containing an essential oil. The massage therapist should ensure that contraindications for any oil are understood if these are to be used. Blending of essential oils must not be carried out by anyone not qualified to make such a preparation and local rules/laws on such manufacture should be followed. Medical history and present complaints are examined in detail to identify any contraindications or potential sensitivities to a particular oil (for example: Are migraine attacks provoked by strong odours? Is the individual epileptic?) and to use the blend to specific effect. The exact amount of carrier oil required varies with the absorptive properties of individual skin, but blending 3–12 drops of essential oil in 30 ml carrier oil is a useful guide. To ensure a pleasant blend, essential oil should be added to the carrier drop by drop, using as little as is required. Blending should only be undertaken by those qualified in aromatherapy. It should be noted that drop size differs between manufacturers and therefore dosage is approximate. The therapist cannot be sure of the exact dose administered (Olleveant et al 1999).

Contraindications

There are few specific recorded contraindications to general aromatherapy, although individual oils have their own specific contraindications and cautions. Obviously, the contraindications for massage should be respected and allergic reactions guarded against. On no account should essential oils come into contact with the eyes. If they do, the eyes should be douched with water and medical help sought. Tea-tree oil should not be used in childbirth as it has been found to reduce uterine contractions in rats (Lis-Balchin et al 2000).

Users of aromatherapy should be aware of a t study reported in the journal Food and Chemical Toxicology which examined the toxic effects of dill, peppermint and pine (Lazutka et al 2001). To summarise: all three oils were found to cause cytotoxic genetic mutations on human lymphocytes. These are worrying findings which raise concerns across all essential oil use. Until more is known about safe doses in humans, it would be wise not to use dill, pine or peppermint oils in massage.

Precautions

Precautions for each oil should be understood. In general (in relation to massage), certain oils should not be used in pregnancy as they have been found to cross the placental barrier in high doses. Oils that contain bergapten (bergamot) can produce ultraviolet sensitisation and phototoxic reactions have been reported (Kaddu et al 2001), so care should be taken, particularly in summer. Oils can cause contact dermatitis. Increased use of lavender flowers around the home and in pillows has been found to cause contact dermatitis (Sugiura et al 2000). Lavender, jasmine, rosewood, laurel, eucalyptus and pomerance have been reported to cause skin reactions (Schaller & Korting 1995). Severe contact dermatitis reactions to tea-tree oil have also been reported (Khanna et al 2000) as has hypersensitivity (Mozelsio et al 2003). Great care should be taken to ensure that susceptibility to adverse reactions is assessed prior to massage. It should also be noted that chemical constituents often behave differently when combined together, so the therapist should be aware that research on individual oils will not provide a total picture. Damaged skin is best avoided except when the practitioner is highly experienced; oils that may provoke sensitivity should not be used on babies and young children.

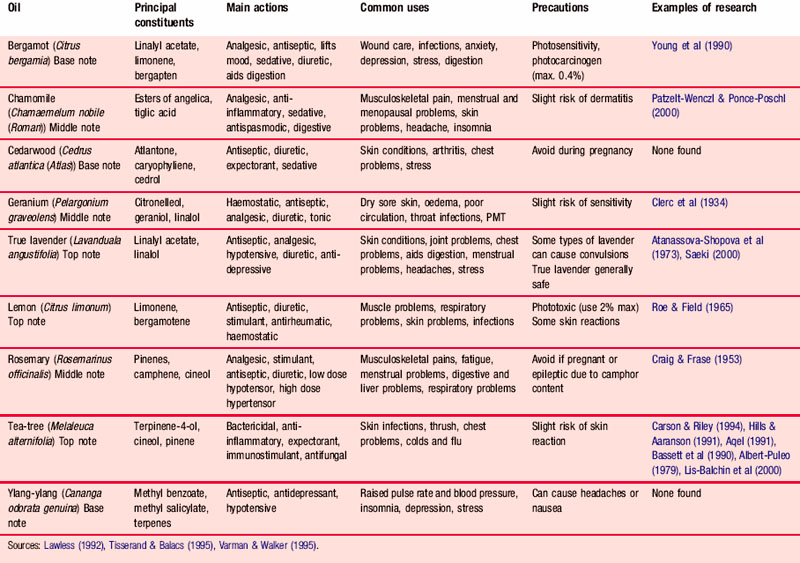

Table 7.1 lists the oils in common use, together with their constituents, main actions and uses. It also summarises the precautions for each oil.

Applying the lubricant

• The lubricant should be at skin temperature. Oil in a sealed container can be warmed by standing it in hot water. Talc can be warmed by being left close to a heat source.

• Avoid spillages. Oil can be transferred into a small squeeze bottle; this is probably the safest method. Alternatively it can be put into a shallow dish and placed on a surface close to the treatment couch but where it is not likely to be upset.

• The therapist’s hands should be washed before beginning the massage.

• The patient’s clothing should be protected.

• Application. The lubricant, be it oil or talc, is first rubbed onto the therapist’s hands and then transferred to the skin of the patient. This method safeguards against applying too much lubricant or spilling it on the patient’s clothing; it also protects the patient from the unpleasant sensation of feeling a sudden dollop of oil.

• The lubricant is spread on the skin by stroking or effleurage.

• Reapplication. During the massage treatment it may be necessary to reapply the lubricant and sometimes it is desirable not to lose physical contact with the patient. The technique is achieved by keeping the dorsum of one hand in contact with the patient so that the palm is upwards and can receive the lubricant from the other hand. The hands are rubbed together, maintaining patient contact, and the lubricant is then reapplied to the skin in the usual way. To achieve this method gracefully the lubricant should be within easy reach of the treatment couch.

• Hygiene. To ensure there is no risk of cross-infection, at the end of treatment the therapist should dispose of any oil that may have become contaminated and thoroughly wash her hands.

Stance, posture and movement

Stance

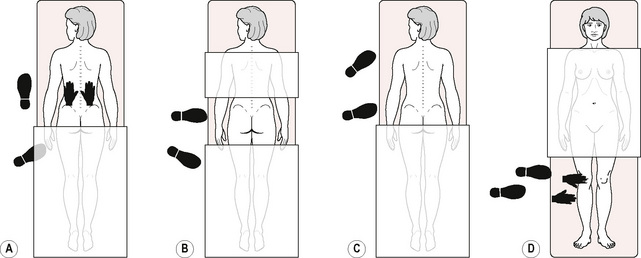

Long manipulations

For effleurage to the back, for example (Fig. 7.1A), the therapist stands close to the left of the treatment couch where she can place her hands at the start of the stroke with no trunk rotation. The left foot is a comfortable stride forward of the right one; the left foot points towards the head of the treatment couch and the right foot is angled. At the start of the stroke there is more weight on the right foot than on the left; the therapist is using some body-weight to create the pressure of the stroke. As the stroke progresses up the back, weight is transferred from the right foot to the left; the left knee flexes so that a lunge position is adopted.

Transverse manipulations

For wringing the back, for example (Fig. 7.1B), the therapist stands close to the treatment couch facing across the patient’s back. The left foot is on a level with the thoracolumbar junction, which is where the manipulation begins. The right foot is angled so that the right lumbar segment can be treated with no trunk rotation. As the strokes move towards the buttocks, the therapist transfers weight to her right leg and flexes the knee. To massage the right thoracic region, the therapist adjusts her foot position so that the right foot is now on a level with the thoracolumbar junction. The procedure is repeated.

Small-range manipulations on a specific structure

For frictions, for example (Fig. 7.1C), the therapist faces the structure to be treated; the left foot is forwards of the right. The left hand is supporting the patient’s thigh while the right hand performs the manipulation. There is more weight being taken through the right foot than the left and, as this is a deep manipulation, there is substantial weight transference to the patient through the therapist’s arms to exert pressure on the tissues.

Posture and movement

• Excessive reaching causes unsafe trunk movements and is linked with muscle fatigue and soft tissue injury.

Prevention: The therapist should stand close to the treatment couch. The correct stance will ensure that she is able to reach all parts of the area to be treated. When a small therapist is treating a very tall patient, it may be helpful to divide the treatment area into sections so that the therapist can change position between segments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree