CHAPTER 26 Managing wound pain

Although not all wounds are painful, in general most acute and chronic wounds cause moderate to severe pain. Management of this pain can be challenging. Given a thoughtful approach and modern pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, most patients can achieve an acceptable level of pain control. The first step in any patient is identifying and measuring the degree, site, and type of pain; a step that guides the appropriate treatment of pain (see Chapter 25). This chapter presents approaches to preventing and managing acute and chronic wound pain.

Nonpharmacologic pain control

Many nonpharmacologic pain control measures are essential when caring for a patient with a wound. A simple and effective intervention is acknowledging a patient’s pain and making a commitment to the patient to address the pain. Explaining the potential harmful effects of pain on healing, along with a careful explanation of how to manage pain, will help to shape the patient’s expectations as well as increase the individual’s sense of control. Both of these strategies may reduce the pain experienced (Acute Pain Management Panel [APMP], 1992). Additional interventions related to pain control begin with controlling and reducing procedural pain or cyclic acute pain through appropriate and conscientious topical care.

Wound cleansing

Avoiding cytotoxic topical agents (e.g., antiseptics, antimicrobials), harsh chemicals, and highly concentrated agents for wound cleansing can significantly reduce wound pain. In general, use of these agents should be avoided unless the wound warrants such intervention (e.g., traumatic wound) and the patient has been adequately anesthetized (van Rijswijk, 1999).

Periwound skin care

Eroded or denuded wound margins can contribute significantly to the pain experienced by the patient with a wound (National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel [NPUAP]-European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel [EPUAP], 2009). Use of skin sealants on intact skin can prevent painful denuding of skin or skin stripping. Use of ointments or skin barriers on open areas can prevent and/or minimize the pain secondary to damaged wound margins.

Debridement

Although many factors are considered when a method of debridement is selected, pain is a frequently neglected consideration. Regardless of the method of debridement selected, pain assessment and management must be considered. Wet-to-dry dressing changes for debridement (nonselective and painful) should be avoided. Using autolysis for debridement, when feasible and appropriate, can significantly reduce the pain associated with debridement (NPUAP-EPUAP, 2009; Robson et al, 2006; Whitney et al, 2006).

Conservative or surgical sharp debridement provokes acute noncyclical pain, which leads patients to ask the clinician to stop the debridement unless they are given additional analgesia or anesthesia (Briggs and Nelson, 2003; Evans and Gray, 2005; Hansson et al, 1993). When sharp debridement is indicated, pharmacologic interventions are an important consideration and are described in detail later in this chapter.

Wound dressings

Many commercially available moisture-retentive dressings are designed for the care of wounds. The main analgesic efficacy of these products appears to stem from their ability to keep the wound moist and protected from the environment, reduce inflammation, and stimulate healing. Moisture-retentive dressings have at least some capacity to reduce pain associated with wounds (NPUAP-EPUAP, 2009; Steed et al, 2006; Whitney et al, 2006). Thus, dressings can be selected with the aim of reducing pain in a particular patient. The most effective dressing will depend on patient factors such as volume of exudate, condition of surrounding skin, wound depth, and necrotic tissue. Dry, wet-to-dry, or wet-to-damp dressings are not moisture retentive and consequently are the most painful. As the gauze dehydrates, it tends to become attached to the wound surface and, along with damaging new granulation tissue, is painful to remove (NPUAP-EPUAP, 2009; Robson et al, 2006; Whitney et al, 2006). The trauma that patients must endure then is multiplied because wet-to-damp or dry dressing must be changed three times per day.

The patient with a wound often dreads the dressing change procedure, which is cyclic in nature. Box 26-1 lists several interventions for pain control during dressing changes. Dressings should be selected that will, upon removal, minimize the degree of sensory stimulus to the wound area (European Wound Management Association [EWMA], 2002).

BOX 26-1 Interventions for Pain Reduction During Dressing Changes

• Minimize degree of sensory stimulus (e.g., drafts from open windows, prodding and poking).

• Allow patient to perform own dressing changes.

• Allow “time-outs” during painful procedures.

• Schedule dressing changes when patient is feeling best.

• Give an analgesic and then schedule dressing change for time of drug’s peak effect.

• Soak dried dressings before removal.

• Avoid use of cytotoxic cleansers.

• Minimize number of dressing changes.

• Position and support wounded area for comfort.

• Consider using low-adhesive or nonadhesive dressings.

• Offer and use distraction techniques (e.g., headphones, TV, music, warm blanket).

Pharmacologic interventions

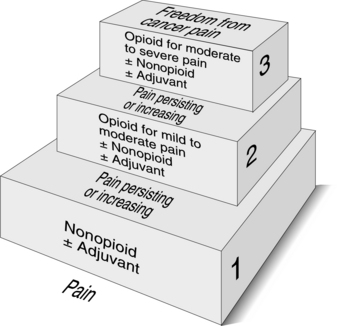

The World Health Organization (WHO) Pain Clinical Ladder, a three-step analgesic ladder approach for the treatment of cancer pain, can also been used to guide the treatment of nonmalignant pain (Boxes 26-2 and 26-3 and Figure 26-1). This approach uses a combination of pain control medications based on assessment of pain intensity. If pain persists after reassessment, the ladder guides the clinician in adding a medication or combination of medications to effectively control pain (McCaffery and Portenoy, 1999). Pharmacologic interventions can be topical, subcutaneous or perineural injectable, or systemic (McCaffery and Beebe, 1989; McCaffery and Portenoy, 1999).

BOX 26-2 World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder (see Figure 26-1)

Step 3

Patients who have severe pain or who fail to achieve adequate relief after appropriate administration of drugs in step 2 of the analgesic ladder should receive an opioid conventionally used for severe pain.

For example: Step 1 medications and morphine (discontinue step 2 medications).

Note: Unrelieved pain should raise a red flag that attracts the clinician’s attention.

From McCaffery M, Portenoy RK: Overview of three groups of analgesics. In McCaffrey M, Pasero C, editors: Pain clinical manual, ed 2, St. Louis, 1999, Mosby.

FIGURE 26-1 World Health Organization analgesic ladder for cancer pain.

(From the World Health Organization, 2010.)

Topical medications

Topical analgesics are commonly used before debridement or before manipulation inside the wound margins, which includes wound packing or application of materials that contact the wound. These medications usually are in the form of a jelly, cream, or ointment, although liquid forms and patches are available. They generally include lidocaine or another local anesthetic with sodium channel receptor blockade activity. Topical anesthetics require at least 15 to 30 minutes to reach optimal analgesic states. Although lidocaine preparations have been widely available and safely used for years, topical use of these preparations in open wounds is considered off label in the United States. Topical lidocaine products should be used with caution, especially with large wounds, to avoid systemic absorption and potential neurologic and/or cardiovascular manifestations.

The most commonly used topical analgesics include 2% and 4% lidocaine jelly, which act on only the superficial layer of tissue and can inactivate exposed wound pain receptors. The strongest evidence base for the effectiveness of topical analgesics in wound care is associated with eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) cream (Astra Pharmaceutics, Wayne, Pa., USA), which contains lidocaine and prilocaine. It is applied 30 to 60 minutes before debridement under occlusion with a film dressing. Instructions for use of EMLA cream are given in Box 26-4 (Evans and Gray, 2005; Hansson et al, 1993).

BOX 26-4 Application of Eutectic Mixture of Local Anesthetics (EMLA) Cream

• 10 g EMLA can safely cover a surface area of approximately 100 cm2.

• Cover with plastic or transparent wrap for 20 minutes.

• If pain is not managed after 20 minutes, increase time to 45 to 60 minutes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree