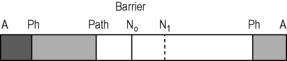

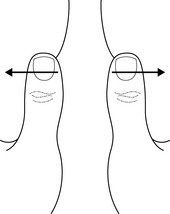

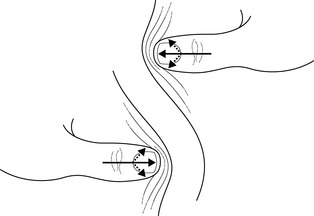

Chapter 7.8 Managing dysfunctional scar tissue Treatment of scars by local anesthesia was first introduced by lay healers, the brothers Huneke, as early as 1947 (Huneke F 1947; Huneke W 1953). They found that they were able to treat painful conditions such as shoulder pain by injecting a scar which was situated at a distance from the painful structure and without any obvious relationship to it. This was followed by what was known in Germany as Neuraltherapie, using local anesthesia for any site of irritation (‘focus’) that might possibly produce a reaction at a distance, for example, in a painful structure. The most prominent author of this trend was Gross (1972). Many of those who used local anesthesia could not fail to notice that using any substance (Kibler 1958) obtained similar effects; for example, Frost et al. (1980), using physiological saline, finally turned to acupuncture. In the end, the scar was almost forgotten. This may explain the lack of pertinent literature (Lewit & Olsanska 2004). Traditional rheumatology deals mainly with inflammatory conditions, in the past called painful conditions of the soft tissues, ‘soft tissue rheumatism,’ using terms such as ‘tendo-vaginitis,’ ‘fibromyalgia’ or “myositis,’ conditions for which no inflammatory origin could be proved (Reveille 1997). The authors suggest that there is currently a lack of sufficient understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of soft tissue, in particular in its relationship to the motor system. For the soft tissues to move in harmony with the motor system, they have to stretch and shift smoothly with every movement of the body – and this is also true of the visceral organs (Ward 1993). Whenever this intricate mobility is impaired, symptoms are bound to occur. However, the authors suggest that these very complex movements are very little understood, and accepted norms are sadly lacking. • Definition: A normal scar (recent or chronic) behaves like any other normal soft tissue; its layers stretch and shift in harmony with the rest of the tissues surrounding the motor system. A scar is considered to be ‘active’ if at least one of its layers does not move in harmony with the rest, i.e., if resistance to passive movement in at least one direction can be palpated. This also applies to visceral organs (Ward 1993). • Diagnosis: For better or worse, palpation is essential in assessment of scars. Starting with the most superficial layers, examination of the skin is most convenient: in a hyperalgesic zone there is increased sweating and the stroking finger immediately feels increased resistance or drag, without causing the patient any discomfort (Lewit 1999). To diagnose one tissue layer after another, the barrier phenomenon is essential (Lewit & Olsanska 2004). A useful definition of the barrier is that it represents the point where the first slight resistance to passive motion is perceived. This depends, of course, on the skill of the examiner. The normal barrier is met only gradually; it easily springs, whereas a pathological barrier is abrupt and barely springs (Fig. 7.8.1). The most superficial layers of the skin can be stretched, and after reaching the barrier, springing can be easily felt (Fig. 7.8.2). Such springing is hardly felt by the patient, but if there is a pathological barrier, he or she may feel a slight pain, like a pin prick. To examine subcutaneous tissue, a skin fold is formed, which is usually thicker in a hyperalgesic zone. This fold can normally be easily stretched (Fig. 7.8.3) but offers increased resistance to stretch in active scars. For treatment, it is suggested that the fold should only be stretched, not squeezed.

History

The ‘active scar’ a model of soft tissue lesions

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine