Management of Glenohumeral Instability with Humeral Bone Loss

Ronak M. Patel

T. Sean Lynch

Nirav H. Amin

Anthony Miniaci

DEFINITION

The glenohumeral joint is one of the most commonly dislocated joints in the body.

With anterior dislocations, bony defects of the anterior glenoid and posterosuperior aspect of the humeral head occur with relative frequency.

Osseous injuries directly impact recurrent instability by altering joint contact area, congruency, and function of the static restraints.3,14,15,25,28

One of the first descriptions of the lesions found on the humeral head was by Flower13 in 1861, with many subsequent investigators reporting on these bony defects.26

In 1940, two radiologists, Hill and Sachs,17 reported that these defects were actually compression fractures produced when the posterolateral humeral head impinged against the anterior rim of the glenoid.

The true incidence of Hill-Sachs lesions is unknown; however, they are associated with approximately 40% to 90% of initial anterior glenohumeral dislocations.7,36,38,41,45

The incidence in recurrent instability can vary up to 70% to 100%, with arthroscopy often identifying lesions not appreciated on imaging.17,38

The management of Hill-Sachs lesions depends mainly on the size of the lesion and whether it is engaging.4

A majority of lesions are small and clinically insignificant.

Often, lesions that are clinically relevant may be indirectly managed with procedures aimed to address primary instability at the glenoid (ie, Bankart repair, glenoid reconstruction, etc.).

ANATOMY

With an anterior shoulder dislocation, the humeral head externally rotates relative to the glenoid while translating anteriorly.

The static glenohumeral restraints (ie, capsule, ligaments, labrum) are stretched or torn with further anterior translation, and dislocation, of the humeral head.

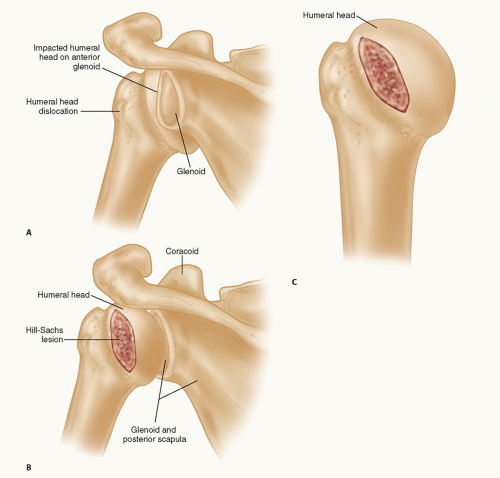

The posterosuperolateral aspect of the humeral head then impacts on the anterior aspect of the glenoid rim and creates a Hill-Sachs lesion (FIG 1A-C).

PATHOGENESIS

The most common mechanism responsible for a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation occurs when an indirect force is applied to an abducted and externally rotated arm.

Palmer and Widen along with Burkhart and De Beer described an “engaging” Hill-Sachs lesion as one that encounters the anterior glenoid rim with the arm in the “active” position of abduction (90 degrees) and external rotation (0 to 135 degrees).4,6,30

These humeral head defects are parallel to the surface of the anterior glenoid when the arm is abducted and externally rotated.1

This has been termed an articular arc deficit as there is disruption of the arc of the glenohumeral articulation when the Hill-Sachs lesion rotates over the anterior glenoid rim.4

Lesions that are not parallel to the glenoid rim in the “active” or “athletic” position do not engage and are termed nonengaging lesions.4,6 The Hill-Sachs defect passes diagonally across the anterior glenoid with external rotation; therefore, there is continual contact of the articulating surfaces and no engagement of the Hill-Sachs lesion by the anterior glenoid.27

Hence, when a patient has symptomatic anterior instability associated with an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion with an articular arc deficit, treatment must be directed at both repairing the Bankart lesion, if present, and preventing the Hill-Sachs lesion from engaging the anterior glenoid.

On an axial view with 0 degrees representing direct anterior, the typical Hill-Sachs lesion lies between 170 and 260 degrees with a midpoint at 209 degrees (FIG 2A,B).35

Cho et al9 looked at three-dimensional (3-D) computed tomography (CT) scans of 107 shoulders undergoing surgery for recurrent anterior instability to preoperatively predict engagement of a Hill-Sachs lesion.

The mean width was 52% (range, 27% to 66%) and depth was 14% (range, 8% to 20%) of the humeral head diameter on axial images.

Hill-Sachs lesions typically are accompanied with other pathology including soft tissue and/or bony Bankart lesions and anterior glenohumeral ligament disruption. Optimal surgical management requires addressing these lesions with or without management of the Hill-Sachs lesion.

Multiple options exist to address Hill-Sachs defects in anterior glenohumeral instability, including humeroplasty, remplissage, allograft reconstruction (osteochondral plugs vs. size-matched bulk allograft), partial resurfacing, and total resurfacing/arthroplasty.

The authors’ preferred technique is an anatomic allograft reconstruction of the humeral head using a side- and sizematched humeral head osteoarticular allograft that eliminates the structural pathology while maintaining the range of motion of the glenohumeral joint.

NATURAL HISTORY

Hovelius et al19 prospectively followed 229 shoulder dislocations for 25 years. All patients were treated nonoperatively initially and prognostic factors, recurrence, and surgical intervention were monitored.

At 10 years, 99 of 185 (53.5%) shoulders that were evaluated with radiographs had evidence of a Hill-Sachs lesion.

Of these 99 shoulders, 60 redislocated at least once and 51 redislocated at least twice during the 10-year follow-up.18

This compares with 38 (44%) of the 86 shoulders that did not have such a lesion documented (P < 0.04).

However, at 25 years, they concluded a small humeral impression fracture at the time of initial dislocation did not influence the recurrence rate.

Rowe et al36 analyzed the long-term results of Bankart repairs for recurrent instability and found an overall recurrence rate of 3.4% (5/145); the recurrence rates were 4.7% and 6% for patients with moderately severe and severe Hill-Sachs lesions, respectively.

Although Rowe et al used 3, 5, and greater than 10 mm depths to differentiate their size of Hill-Sachs lesions, various methods of determining size and/or volume of the humeral head defect have been proposed without consensus; these include Hill-Sachs quotient, articular arc circumference, and Hill-Sachs angle.6,8,9,20,23,26,37,39

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

All patients are initially evaluated with a complete history and physical examination.

Specifics of the history include questioning about the mechanism of instability and timing of initial symptoms and about the details of presenting symptoms, including pain, frequency, instability, and level of function.

Arm position and amount of force required for instability may be an evolving process.

Pertinent medical history including collagen disorders or epilepsy should be noted.

All previous surgical procedures performed on the shoulder should be noted.

Many patients will give a history of recurrent dislocations or multiple surgical attempts to correct the instability.

Physical examination should focus on inspection for previous scars, gross asymmetry, a thorough comparison of active and passive range of motion, strength testing, particularly, evaluation of the integrity and strength of the rotator cuff, and axillary nerve function.

The clinician should perform a detailed examination for glenohumeral laxity in the anterior, posterior, and inferior directions.

Examination for apprehension should be performed in multiple positions (ie, sitting, standing, supine) as patients with large Hill-Sachs lesions usually exhibit apprehension that often occurs with the arm in significantly less than 90 degrees abduction and 90 degrees external rotation.26,27

Anterior apprehension test: Positive apprehension can be associated with anterior labral injuries.

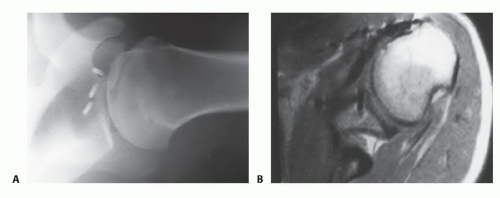

FIG 3 • A. Axillary radiograph of shoulder demonstrating a large Hill-Sachs lesion. B. Axial MRI image demonstrating large engaging Hill-Sachs lesion.

Bony apprehension test: Apprehension with fewer degrees of abduction may indicate a significant and symptomatic bony contribution to the instability.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Preoperative imaging includes a comprehensive radiographic evaluation with anteroposterior (AP), true AP, axillary, and Stryker notch views of the involved shoulder (FIG 3A).

All patients require a preoperative axial imaging study (CT > magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) to more fully define the bony architecture of the glenoid and humeral head (FIG 3B).

A 3-D reconstruction can be a useful tool to more clearly define the size and location of the defect and to estimate the amount of the articular surface involved.

Although the volume and depth of the lesion certainly affect the stability of the shoulder, even more important may be the size of the defect in the articular arc.

In imaging, the plane of the Hill-Sachs defect is oblique to the plane of the axial image; therefore, the size of these

defects, and even occurrence is often underestimated with standard axial imaging.38

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Anterior shoulder dislocation with or without the following:

Bankart lesion

“Bony Bankart” or an anterior glenoid lesion

Hill-Sachs lesion

Combination of the aforementioned

Posterior shoulder dislocation with or without associated soft tissue and bony lesions

Inferior shoulder dislocation with or without associated soft tissue and bony lesions

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Small osseous lesions and nonengaging Hill-Sachs lesions can be managed nonoperatively. Often, combined humeral head and glenoid injuries may be treated with addressing the primary defect alone (ie, Bankart, humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament [HAGL], or glenoid bone loss).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree