Lumbar Decompression

Bradley K. Weiner

Ronald Mitchell

DEFINITION

Degenerative changes that are part of the aging process may lead to compression of neurologic tissues within the spinal canal or subarticular zones (with or without the foraminal zone) of the lumbar spine.

This spinal canal stenosis may lead to neurogenic claudication or a monoradiculopathy.

ANATOMY

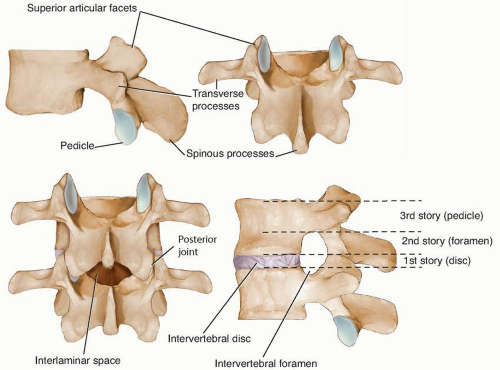

The functional vertebral unit is depicted in FIG 1. More details are given in the anatomy section of Chapter 11.

Spinal canal stenosis is best classified based on vertical extent of compression, regions of the canal involved, and severity of the involvement.

Accurate anatomic classification facilitates preoperative planning and can minimize the risk of surgical complications such as missed pathology and iatrogenic root injury.

PATHOGENESIS

Degenerative changes can affect the disc, the soft tissues, and the facet joints of the spinal unit.

Annular bulging of the disc, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy and infolding, and osteophyte formation on the facet joints can contribute to neurologic compression. Occasionally, epidural lipomatosis also contributes to spinal stenosis, especially in the presence of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM).

This compression occurs slowly and gradually affects the blood supply (arterial inflow and venous outflow) of traversing nerve roots and the free flow of cerebrospinal fluid within the common dural sac. When increased demands are placed, as in walking, the nutritional needs of the nerve roots cannot be met and noxious by-products of metabolism cannot be removed, resulting in neurophysiologic malfunction characterized clinically by paresthetic and cramping symptoms in the legs.

As in lumbar disc herniations, many patients with spinal stenosis are asymptomatic, suggesting that other factors intrinsic to nerve root function and adaptability are equally important (eg, smoking, vascular disease, diabetes).

NATURAL HISTORY

Patients with mild to moderate symptoms and mild to moderate neurologic compression may respond to conservative care. Unless the compression increases, symptoms generally remain stable, with minimal resolution and minimal worsening.

The more severe the symptoms and the more severe the neurologic compression, the more likely symptoms will progress, the less likely they will respond to conservative measures, and the more likely patients will seek surgical intervention.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Symptomatic patients with spinal canal stenosis generally present with neurogenic claudication (70%), monoradiculopathy (15%), or a combination of the two.

Foraminal stenosis (10% to 15% of cases) is best diagnosed clinically by a severe monoradiculopathy of an exiting nerve root, and radiographically on parasagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging or computed tomography (CT) sagittal reconstruction (FIG 2).

IMAGING

As described in Chapter 11, MRI is the imaging study of choice for the diagnosis and anatomic classification of spinal canal stenosis.

CT myelography is invasive and can better resolve the bony component of stenosis compared to MRI. Myelograms taken in flexion-extension may demonstrate a dynamic component to the stenosis. CT myelograms may be particularly useful in patients who have had prior surgery (where MRI may be difficult to interpret due to scarring) and in those with associated spinal deformity (eg, scoliosis).

Plain radiographs are useful in demonstrating instability in the coronal (lateral listhesis) or sagittal (spondylolisthesis) planes that may need to be addressed with fusion in addition to decompression. Upright anteroposterior, lateral, and flexion-extension views can be obtained.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Vascular claudication, bilateral hip osteoarthritis, peripheral neuropathy, and “pump problems” such as congestive heart failure or coronary artery disease resulting in poor peripheral vascular flow

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Patients with mild claudicant symptoms or a monoradiculopathy may respond to physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and epidural or root sleeve steroid injections. Although some patients may relapse into symptoms, many in this group are content to repeat these efforts or to live with their symptoms.

Patients with significant claudication generally do not respond to nonoperative measures, or they respond only temporarily. Most will elect to undergo operative decompression. Similar to disc herniations, absolute surgical indications include a cauda equina syndrome and progressive neurologic deficits.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The evidence base is clear: Decompressive laminectomy or laminotomy is the operative technique with the best-documented long-term outcomes and is the gold standard of surgery for spinal canal stenosis. In those patients having failed basic conservative measures, the long-term outcomes of decompression are superior to continued nonoperative measures.

Preoperative Planning

Planning is vital and should aim to answer several questions:

What is the patient’s clinical syndrome?

What levels are involved?

Is the involvement “intersegmental”?

Are the foramina involved?

Is there associated pathology: disc herniation, synovial cyst, or degenerative spondylolisthesis or lateral listhesis?

The answers to these questions will direct the surgical approach, with the goal being complete and safe decompression of compressed neurologic tissue while minimizing damage to tissues not directly involved in the pathologic process.

Positioning

Prone positioning on a well-padded frame is used (generally the Andrew, Wilson, or Jackson; see Fig 4A in Chap. 11). The hips and knees are gently flexed to decrease lumbar lordosis and to facilitate the interlaminar approach. The abdomen is free to decrease intra-abdominal pressure and venous backflow into the canal.

Shoulders should be gently flexed and abducted to less than 90 degrees; eyes, elbows, knees, and feet need to be well padded.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree