Living ethically as a member of the health care team

Objectives

• Discuss several reasonable expectations a health professional can have of professional peers.

• Outline the appropriate steps to be taken in a whistle-blowing situation.

New terms and ideas you will encounter in this chapter

health care team

dual relationship

supererogatory

peer evaluation

peer review

whistle blowers/whistle blowing

impairment

Topics in this chapter introduced in earlier chapters

| Topic | Introduced in chapter |

| Ethical dilemma | 3 |

| Faithfulness or fidelity | 4 |

| Beneficence | 4 |

| Justice or fairness | 4 |

| Nonmaleficence | 4 |

| Deontology | 4 |

| Utilitarianism | 4 |

| Ethical reasoning | 4 |

| Six-step process of ethical decision making | 5 |

| Self care as a responsibility | 7 |

Introduction

This chapter launches a new focus. Up until now, you have been considering your moral agency role as an individual student or professional. But you are a moral agent in respect to other roles you assume, too, one of the most interesting being as a member of a health care team. A health care team is a group of professionals, sometimes with adjunct staff to assist, that becomes the unit of decision making. A team is designed to meet the same ethical goals of a caring response as individual professionals so that members of a team, working together, will accomplish collectively what individual professionals aim to do. You have already seen some examples of professionals working together to provide optimally competent care to patients. Now you will observe them as they also participate in other team activities, demonstrating that the search for a caring response to them can be as important for good patient care as is your commitment to finding a caring response toward a patient. Usually, the two focuses of your care are completely compatible with your ultimate goal of doing what is best for each patient. In fact, team-oriented care was designed to enhance the effectiveness of this goal. Occasionally, however, problems arise within teamwork that threaten to compromise the patient’s good, the team’s effectiveness, or both. You have an opportunity here to examine both some strengths and challenges in teamwork. The story of Maureen Sitler and Daniela Green is one example of how conflict or questions arise about the ethically right thing to do.

You will have an opportunity to reflect on this story throughout the chapter because it highlights several strengths and types of ethical challenges that you could face—and probably will face—in your role as a team member. The first thing we will consider is the importance of providing support to and accepting support from each other as teammates.

The goal: a caring response

No one who works in the health care setting day in and day out escapes moments of self-doubt, anger, or utter frustration. As you read in Chapters 6, 7, and 8, a great deal is expected of you in regard to taking good care of yourself as a student or professional and in getting along in the organizational structures of health care. Even so, at times, your involvement in the human suffering of illness and disease is intense, the responsibilities arduous, and the challenges monumental. The wear and tear of taxing schedules, patients whose problems seem overwhelming, or a day in which everything that could go wrong does can discourage even the most competent, optimistic person.

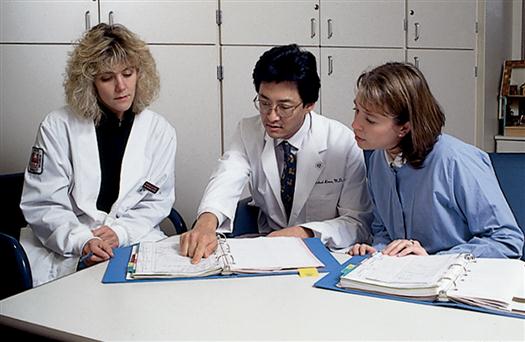

Being a member of a health care team is one of the most fundamental facts of life in today’s health care system, and when the team is working well together, it is one of the most certain hedges against being worn down by the challenges of your work (Figure 9-1).

Maureen Sitler’s situation illustrates well how understandable (and how wonderful) it is to develop friendships in the workplace. It is not surprising, considering that you will spend some of the best (and if not the best, at least the most) hours of your life in workplace settings. Friendships, a love relationship, and business partnerships with people you will meet first as a team member are all within the realm of possibility.

Many institutions currently recognize the need for team support. In some institutions, there is an effort to hold departmental or interdepartmental meetings so that issues may be addressed in a nonthreatening, supportive setting. This type of arrangement usually improves and sustains good working relationships among team members and provides a refuge where individuals can receive needed support. They provide opportunities for deliberation, negotiation, and communication clarification to facilitate consensus building in complex situations. In any department, such arrangements can help to humanize the environment for workers and patients alike.1 In this regard, it makes sense to think of teamwork as the institution’s acknowledgment of such stresses and the implementation of actual mechanisms to address them as its caring response to the situation.

In the previous chapter, we suggested some ways to “check out” the health care environment when applying for a new position in a health care setting. Wisdom counsels that in your fact finding, you inquire whether there is a support network among team members as well. To make an assessment, the following suggestions may help:

Reflection

What other questions or concerns would you address when applying for a position and trying to assess how well key team members seem to work together? List them here.

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

Fortunately, it is highly probable that you will find a supportive net of team members in your work setting. Once you are employed, or if you already are, you can help create a greater support network among team members by being attentive to the blahs and blues that a colleague seems to be experiencing, by risking sharing your own “doubts or discouragements” with people you judge to be trustworthy to help you through them, and by making suggestions regarding the need for mechanisms designed to work through problems as a team. As Maureen’s situation implies, friendships may take root in the shared experiences, concerns, and time spent with other members of the health care team. A friend you meet in a work situation may become the key figure in building a supportive network, and as friends, the two of you can provide support to each other and others. The joy of discovering and cultivating such a friendship is among the most rewarding of the many fringe benefits of a health professional’s career.

The ethical components guiding close, convivial working relationships are similar to those in the health professional–patient relationship.2 Team members also should be recipients of caring responses from you and others. Some ways to achieve these responses include telling the truth, honoring confidences, acting with compassion, and respecting the dignity of your colleagues.3

Reflection

Because you are a moral agent with the responsibilities associated with it, what do you think you should be able to reasonably expect from your fellow teammates? Name some things that would indicate that you are the beneficiary of their respect and care.

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

From our own experience, we have developed a list of reasonable expectations regarding team relationships—things we believe one should be able to count on based on the ethical principle of fidelity to each other. These expectations are:

1. Collegial trust and the shared goal of a caring response.

3. A willingness by all teammates to carry a fair share of the workload.

4. Sympathetic understanding regarding work-related stresses.

7. Encouragement to develop both professionally and personally within the work environment.

As you think of other things you would expect and want to help protect and encourage, be bold in making suggestions to those with whom you work. Sometimes a well-placed word can help to increase everyone’s imagination about how the team can work together more effectively.

With the background established thus far in this chapter, turn to the six-step process of ethical decision making to learn how it also applies to team issues.

The six-step process and team decisions

We take Maureen’s situation, with its potential for favoritism toward Daniela, to give you an opportunity to apply the process of ethical decision making introduced in Chapter 5. So far, you have applied it to situations involving health professionals’ decisions regarding direct patient care and organizational dimensions of your work. At the same time, interprofessional issues also will arise among team members, and those issues lend themselves to analysis and (hopefully) resolution by use of the same process. Some ethical considerations you have not yet encountered must be taken into account in a team peer relationship. The last part of this chapter focuses on the challenges of peer review and the duty to report unacceptable conduct of a teammate.

Step 1: gather relevant information

Maureen has to gather all the relevant information about the patients on the waiting list that she would be morally obligated to do in any event. However, right away you can see that her discovery of Daniela as one of her potential patients complicates the situation in at least two ways: she has to decide whether her loyalty to her team member should have any bearing on her choice, and she has to reckon with the fact that the two of them are now in a “dual role” with each other (i.e., as colleagues and also as professional-patient) if Daniela becomes her patient.

Team loyalty as relevant information

We surmise that because Daniela is Maureen’s colleague this factor alone is influencing Maureen’s ethical reasoning. No one would question how important it is to provide support to professional peers, and now here is a peer with a need to which Maureen is able to respond. It takes little imagination to understand why Maureen’s emotional response is to immediately accept her as one of the patients. It would be easy to give Daniela the VIP (“very important person”) treatment, slipping her in ahead of the others in the busy schedule, regardless of whether she will benefit the most. We do not know exactly why Tom urges Maureen to “fit her in.” His statement may be based on something he knows about her physical situation relative to the others on the list. More likely, he is responding to the same urgings that Maureen is experiencing. He might also be imagining the backlash among their other teammates and professional colleagues throughout the institution if word gets out that Daniela was not given high priority knowing that teams have a shared responsibility for their decisions and outcomes.4 Maureen probably is well aware of these relevant “facts” of the situation.

The ethical challenge of dual roles

The two women are not only teammates but also enjoy a warm personal relationship. In other words, they are in a relationship both as peers and as friends. Now they are plunged into a third type of relationship: they are about to encounter each other as therapist and patient in a health professional–patient relationship. Within health care settings, this type of situation is referred to in the literature and ethical guidelines as a dual relationship.

The situation of a dual relationship is always one occasion for careful reflection about appropriate boundaries in the professional setting.4 As Maureen tries to sort out her priorities in her role as a health professional, who will be treating the patient, Daniela, she becomes strikingly aware that she and Daniela are in a new psychological dynamic with each other. The health professional–patient relationship has ethical parameters that do not pertain to their relationship either as professional peers or as friends. In her professional role, if Maureen’s favorable bias toward Daniela becomes an occasion for allowing an uncaring response to the other patients on the list, she will have acted unethically. Although Daniela may accept this situation with equanimity and understanding, anyone who has been very ill knows that it is difficult not to want attention immediately. The favoritism one would automatically hope for and reasonably expect from a friend is not alone sufficient reason for Daniela to receive top priority treatment as a patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree