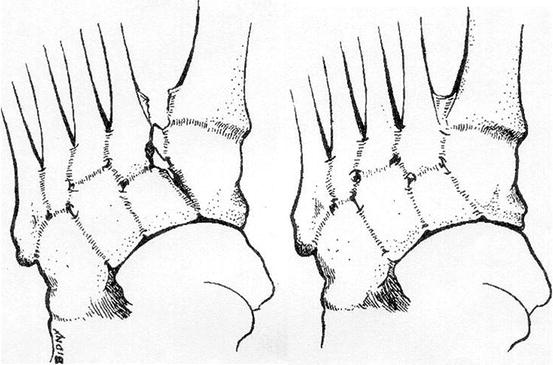

Fig. 5.1

Common mechanism of injury in sports

5.1 Anatomy, Biomechanics, and Evaluation

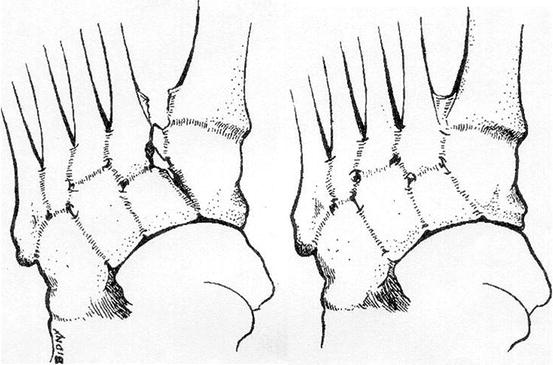

Axial loading of the metatarsals can cause fracture and diastasis/dislocation, particularly in regards to the second metatarsal base and medial cuneiform. Normally the second metatarsal base is the “keystone” to the midfoot arch in the frontal plane and should be the “high point”. The relationship of each metatarsal to their respective tarsal bone they articulate with is critical as is the distance between the second metatarsal and the first (medial) cuneiform. After midfoot injury, weight-bearing and oblique radiographs should show off-set (mal-alignment) of no more than 1 mm with the metatarsals to their respective tarsals. Ideally, though the region of the main Lisfranc’s ligaments (spanning between the second metatarsal and the first cuneiform) can have an acceptable difference to the asymptomatic foot of 2 mm. These dislocations are best seen with weight-bearing X-rays. A “fleck” sign is often seen with the Lisfranc’s ligament avulsion (Fig. 5.2). CT/MRI may be warranted.6 Nunley and Vertullo described a classification system where Stage I was a sprain with no diastasis and is treated nonsurgically, Stage II diastasis of 2–5 mm with no loss of arch height while Stage III exhibits loss of arch height along with abnormal diastasis, both of which are treated surgically.3

Fig. 5.2

“Fleck” sign from lateral Lisfranc’s ligament attachment

5.2 Clinical Presentation

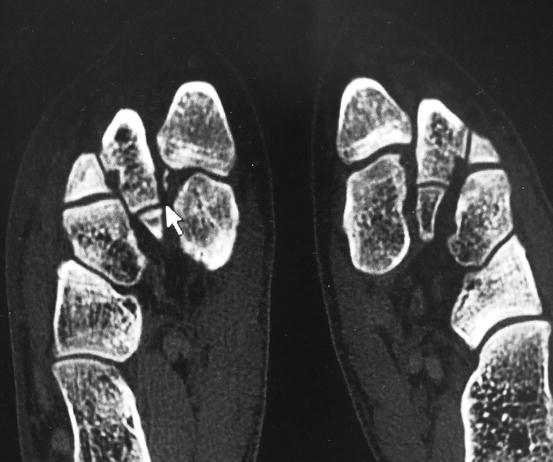

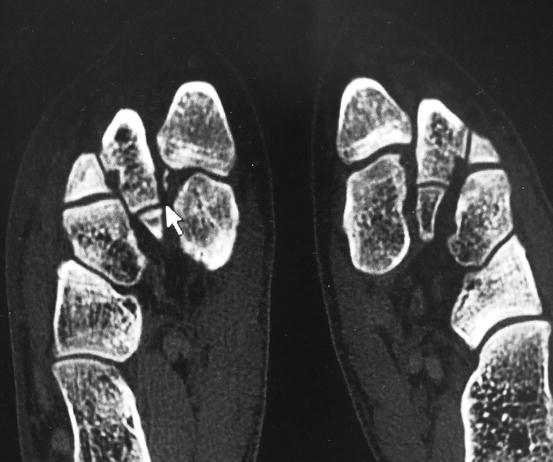

The typical presentation in sports is an athlete complaining of pain on top of the foot after a forefoot twist, loading injury, or a fall. Patients may have felt or heard a “pop”. Edema and ecchymosis maybe be present, especially with fracture. Compartment syndrome can occur with severe injuries and should be addressed acutely. Subtle Lisfranc’s injuries such as milder sprains may have minimal edema and no ecchymosis. Provocative maneuvers include frontal plane stress of the metatarsals against the tarsals, or between the midfoot bones. A good test for Lisfranc’s ligament involvement is moving the first and second metatarsals in opposite directions to provoke pain (Fig. 5.3). This is indicative of a Lisfranc’s injury. Weight-bearing (unshod) examination for symmetry especially of arch height is performed if possible. If pain and edema does not allow for comparison weightbearing examination and X-rays, patients should have careful inspection of their non-weight-bearing films; if fracture or dislocation is suspected, a CT should be performed (Figs. 5.4 and 5.5). Initial treatment consists of non-weight bearing, compression dressing, posterior splint or cast boot, and ice packs behind the knee or ice bucket submersion for 15 min four times/day.

Fig. 5.3

Stress maneuver of Lisfranc’s joint

Fig. 5.4

Preoperative weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP) X-ray showing widening

Fig. 5.5

Preoperative CT

5.3 Treatment

Lisfranc’s and midfoot sprains can be treated nonsurgically when the corresponding articulations are not disrupted more than 2 mm with weight-bearing images.1–5 If there is widening of more than 4 mm of Lisfranc’s ligament or off-set of 2 mm or more, surgery should be considered (Fig. 5.4). Stabilization is achieved, often with screw fixation. With severely comminuted intra-articular injuries, primary arthrodesis, particularly in the medial three Lisfranc’s articulations, can be considered. Bioabsorbable screws can be utilized for open-reduction internal fixation (ORIF) as they may decrease the need for hardware removal at a later date.4,5 (Fig. 5.6) In chronic cases where arthrodesis is not preferred (such as in athletes), a “soft” fusion with bioabsorbable or metallic screws may be needed. An incision to expose the first and second tarso-metatarsal articulations may be needed to remove fibrotic tissue so that realignment can be achieved. As with any surgery in this region, great care should be taken to avoid traumatizing the neurovascular structures.