Lapidus Procedure for Hallux Valgus Deformity

Lew C. Schon

Samuel B. Adams Jr

Arthrodesis of the first metatarsocuneiform (MTC) joint in conjunction with distal soft tissue procedure for the correction of a hallux valgus (HV) deformity was promoted by Lapidus during the 1930s through the 1960s (1, 2 and 3). Although not the originator of this technique, Lapidus reported on it to stress his perception of the mechanical importance of metatarsus primus varus as one of the most common causes and most prominent factors of HV deformity. His original description of the procedure involved arthrodesis of the first tarsometatarsal joint with the creation of a bony bridge between the bases of the first and second metatarsals and a distal soft tissue release. Over his career, Lapidus modified his technique and narrowed his indications for the procedure.

In the past four decades since Lapidus last reported his work, the indications for performing this surgery have significantly changed and many modifications to the procedure have been proposed (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10). Nonetheless, the goals of this operation have remained the same: to correct and stabilize the first metatarsal at the apex of the deformity.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The primary indication for this procedure remains HV deformity associated with metatarsus primus varus and a hypermobile first ray. First MTC arthrodesis is generally performed for moderate to severe HV deformity with an HV angle of greater than 30° and an intermetatarsal (IM) angle of 14° or more (Fig. 8.1). If metatarsus adductus is present, however, the IM 1-2 angle may measure less than 14°, even though the position of the first metatarsal with respect to the longitudinal axis of the foot is in marked varus (Fig. 8.2). Other indications for this operation are HV and severe metatarsus primus varus associated with generalized ligamentous laxity or MTC arthritis. The adolescent bunion with moderate to severe deformity is at a high risk for recurrence and has been successfully treated with the first MTC arthrodesis when the epiphysis has closed. Additionally, patients who have failed previous bunionectomy are often good candidates for the procedure. Severe deformities that occur in osteopenic feet may fare better with fixation at the MTC level than the proximal aspect of the first metatarsal. Although this is a good choice of operation for correction of severe HV, it is our opinion that it should be used only if the MTC joint is hypermobile or arthritic. The procedure is generally used in the younger age group and less frequently used in the elderly population. Older patients often fare better with other procedures with less potential morbidity, with which they may be ambulatory immediately postoperatively. Modern fixation techniques may obviate this relative contraindication by providing earlier return to weight bearing.

This procedure is contraindicated in dancers or athletes, who typically require maximum joint flexibility during their desired activities. Additionally, this procedure is contraindicated in juvenile patients with an open epiphysis, noncompliant patients, or those with Charcot arthropathy. Other relative contraindications include patients who have symptomatic arthritis of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint as realignment may exacerbate the pain. In these cases, arthrodesis

of the first MTC, which may ultimately be necessary, may result in a transfer of stress to the adjacent joints causing the first MTP to become more symptomatic. Patients who have short first metatarsals may suffer from additional inherent shortening from the Lapidus procedure that may precipitate symptoms from second MTP overload. In these cases, if first MTC arthrodesis is planned, a concomitant procedure to lengthen the first metatarsal should be undertaken. At times, a plantar translation could permit better weight bearing when there is less severe shortening. Preexisting

sesamoiditis may be a relative contraindication to this surgery because the absence of mobility and stress dissipation from the first MTC joint will result in increased pain underneath the first metatarsal head.

of the first MTC, which may ultimately be necessary, may result in a transfer of stress to the adjacent joints causing the first MTP to become more symptomatic. Patients who have short first metatarsals may suffer from additional inherent shortening from the Lapidus procedure that may precipitate symptoms from second MTP overload. In these cases, if first MTC arthrodesis is planned, a concomitant procedure to lengthen the first metatarsal should be undertaken. At times, a plantar translation could permit better weight bearing when there is less severe shortening. Preexisting

sesamoiditis may be a relative contraindication to this surgery because the absence of mobility and stress dissipation from the first MTC joint will result in increased pain underneath the first metatarsal head.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A general assessment of a patient’s alertness and mental status will help determine his or her compliance for the surgical reconstruction. Ligamentous laxity observed throughout the musculoskeletal system lends support to choosing an MTC arthrodesis over a proximal first metatarsal osteotomy. Overall alignment of the lower extremity should be observed statically and dynamically to identify etiologic factors that may influence the outcome. Patients with acquired flatfoot deformity may need to have a reconstruction of their dysfunctional posterior tibial tendon with operations such as calcaneal osteotomy and flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendon transfer. Palpation of the pulses is critical to determine whether there is adequate vascularity and to assess the position of the dorsalis pedis relative to the MTC joint. It is often possible to palpate the medial dorsal cutaneous nerve, which is vulnerable to iatrogenic injury.

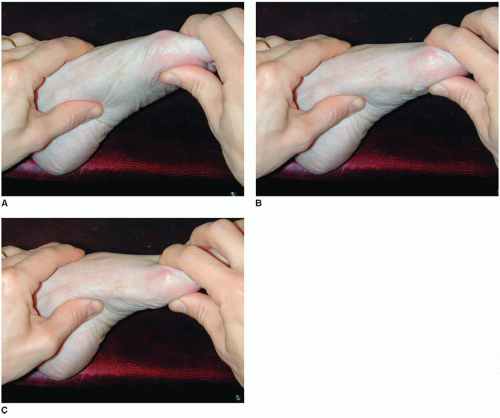

In addition to observing parameters such as the size and shape of the foot, the range of motion of the entire foot and ankle is assessed. Crepitus and restricted mobility in adjacent joints should be determined, because these joints may become more symptomatic after MTC arthrodesis. The second and third MTC joints should be evaluated, especially in cases of arthritis or more severe deformity, because it is occasionally necessary to extend the fusion to incorporate these joints. Hypermobility of the first ray is evaluated by grasping the first metatarsal with the examiner’s hand while stabilizing the rest of the foot with the other hand (11,12). While the midfoot is held stable, the thumb and forefinger of the opposite hand manipulate the first metatarsal in a dorsal-plantar plane (Fig. 8.3). The joint then is placed through a rotational arc (supination-pronation). Particular attention is paid to the increased arc of motion in the dorsal direction, which is associated with dorsal elevation or prominence of the first metatarsal and weight transfer to the second metatarsal. By abducting and adducting the metatarsal, medial-lateral stability is checked.

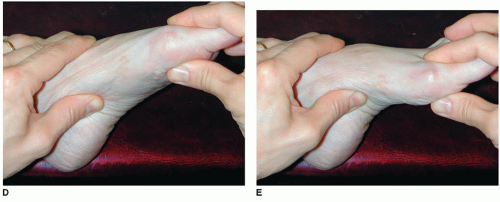

In cases of first MTC hypermobility, it is important to assess first MTP motion with the first metatarsal reduced to proper alignment. This will allow for an estimate of postoperative first MTP range of motion and congruency (Fig. 8.4). Additionally, first MTC hypermobility can present as transfer metatarsalgia to the second ray, causing plantar callus formation (Fig. 8.5) and second MTP joint synovitis with subsequent subluxation and hammer toe formation.

Weight-bearing radiographs should be obtained. Measurements of the 1-2 IM angle, first MTC angle, and HV angle are made. The presence of metatarsus adductus, the lengths of the first and second metatarsals, and the congruity of the hallux MTP joint are noted. On the weight-bearing radiographs, several findings are indicative of first MTC instability (hypermobility), including loss of alignment between the first metatarsal and the medial cuneiform resulting in medial or dorsal translation of the first metatarsal (Figs. 8.6 and 8.7) and a break in the axis of the medial column that occurs at the first metatarsal–medial cuneiform joint resulting in a plantar gap or widening between the joint surfaces (Fig. 8.8). Hypermobility is suggested radiographically as increased cortical hypertrophy along the medial border of the second metatarsal shaft (Fig. 8.9).

FIGURE 8.7 Dorsal translation of the first metatarsal relative to the cuneiform is seen in this lateral, weight-bearing radiograph. The midfoot is highlighted to enhance the image. |

FIGURE 8.8 Widening of the plantar gap between the first metatarsal and the cuneiform. Inset: The first metatarsal and medial cuneiform are highlighted to demonstrate instability. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree