Knee Dislocations

Anikar Chhabra

Shane T. Seroyer

Christopher D. Harner

Indications/Contraindications

Traumatic knee dislocations are serious injuries with devastating complications secondary to damage to multiple soft-tissue and stabilizing structures. Associated injuries may include the cruciate ligaments, collateral ligaments, medial and lateral capsular structures, menisci and articular cartilage, as well as neurovascular injuries and compartment syndrome. Traditional nonoperative treatment has resulted in poor outcomes. Surgical treatment remains controversial with respect to timing of surgery, which structures to repair versus reconstruct, and choice of grafts. We believe early surgical repair is indicated in the vast majority of multiligament injuries that result from knee dislocation.

Due to the severity of these injuries, the patient must undergo an extensive preoperative workup to discern the details of his or her injury and to insure he or she is medically stable for surgery. Inherent in this evaluation is detailed attention to factors that may predicate emergent surgical intervention. Evaluation in the trauma bay that reveals an open dislocation, irreducible dislocation, or arterial injury requires an emergency trip to the operating room. In the case of arterial injury, application of a joint-spanning external fixator provides joint stability and protects the vascular graft. Recovery of associated soft-tissue injury determines whether to perform later reconstruction or repair of the ligaments. Following a vascular repair, reconstructive procedures should be postponed until the vascular graft has matured and is not likely to be compromised. After vascular repairs, four-compartment fasciotomies are often required to combat reperfusion injuries.

Elderly, sedentary, or other moribund patients with preexisting functional deficits are not usually candidates for surgical repair and are often better treated with bracing and a functional rehabilitation protocol. Other contraindications to surgery are an active infection, displaced intra-articular or peri-articular fractures of the femur or tibia, and advanced osteoarthritis of the knee.

Preoperative Planning

The preoperative planning for treatment of a knee dislocation begins in the emergency room and requires a very detailed physical exam as well as specific radiological exams, including angiography, to elucidate the extent of the injury. Early vascular surgery consultation is recommended because a normal physical exam does not rule out vascular injury in the acute phase. The physician must also maintain a high index of suspicion for compartment syndrome. The physical exam in these patients can be difficult and inaccurate secondary to pain. Prompt reduction of the dislocation by traction and countertraction under conscious sedation is essential. Appropriate films should be obtained to rule out fractures and to ensure reduction. Stress radiographs may occasionally be used to evaluate varus and valgus instability. Due to the limits of the physical exam, when the patient is medically stable, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is necessary to assess the extent of injury and to assist in surgical planning. Soft tissue swelling and generalized edema may hinder the quality of the MRI obtained.

Controversies

Numerous controversies remain regarding the surgical management of knee dislocation and include timing of surgery: what structures to repair or reconstruct, the choice of grafts, and the surgical techniques. Recent publications have shown that operative treatment gives better results than nonoperative treatment. Although there are numerous approaches and techniques for these difficult cases, this chapter will present our experience and approach to the knee-dislocation patient.

In studies at our institution, patients who undergo acute ligamentous repair and reconstruction within 3 weeks of injury have done better than patients reconstructed after 3 weeks, as determined by Lysholm and Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living scores. However, in patients with severe, life-threatening or arterial injuries, or those with open dislocations, ligamentous reconstruction is delayed until soft-tissue swelling has subsided and the patient’s condition has improved.

The decision to repair versus reconstruct the soft tissues remains controversial. We believe that the repair and reconstruction of all associated ligamentous and meniscal injuries should be undertaken in patients having surgery. The majority of injuries to the cruciate ligaments are intrasubstance and do not respond favorably to primary repair. An exception to this is when large bony fragments from the tibial insertions of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) are avulsed. In these situations we advocate primary repair by passing large nonabsorbable sutures into the bony fragment and through the bone tunnels in the tibia. In all other situations, we reconstruct ACL and PCL injuries. At our institution we attempt to preserve specific bundles of the PCL that are not injured. In one third of cases, the anterolateral bundle is ruptured, but the meniscofemoral ligament and the posteromedial bundle remain intact. In these cases we do a single bundle reconstruction of the anterolateral bundle.

For medial- and lateral-sided collateral and capsular injuries, we often acutely repair (less than 3 weeks after injury) the injured structures if the tissue quality is adequate. Depending on the stability of the repair, augmentation is often necessary. Chronic injuries (more than 3 weeks after injury) tend to be limited by scar formation and soft-tissue contracture and require reconstruction.

To decrease operative time, limit skin incisions in the traumatized knee, and decrease donor site morbidity, we advocate the use of allografts over autografts in multiple-ligament reconstruction surgery. Inherent in this choice of allografts is the risk of transmissible disease with allografts. This must be discussed with the patient prior to the procedure.

Surgery

Anesthesia

The choice of anesthetic is made in conjunction with the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and the patient, taking medical co-morbidities, age, and prior history with anesthesia into consideration.

General anesthesia with concomitant IV sedation is most commonly performed. Preoperative femoral and/or sciatic nerve blocks are routinely performed as an adjuvant for postoperative pain relief. A Foley catheter may be placed intraoperatively to monitor fluid shifts during the procedure.

General anesthesia with concomitant IV sedation is most commonly performed. Preoperative femoral and/or sciatic nerve blocks are routinely performed as an adjuvant for postoperative pain relief. A Foley catheter may be placed intraoperatively to monitor fluid shifts during the procedure.

Setup, Patient Positioning, and Exam under Anesthesia

The patient is placed supine on the operating room table. The goal is to allow up to 80 to 90 degrees of static flexion of the knee to be maintained without manual assistance. To do so, a small bump is placed under the patients leg just distal to the greater trochanter with a lateral post placed at the same level. A sterile bump is wedged between the post and the thigh. To maintain flexion, the heel rests on a 4.5 kg sandbag that has been taped to the bed and prevents extension of the leg (Fig. 25.1). Due to the length of time these cases require, we do not use a tourniquet.

After properly positioning the patient on the operating table, a complete ligamentous exam, including anterior and posterior drawer tests, pivot shift, dial test, and posterior drawer with external rotation, is performed. These exam findings are corroborated with MRI findings to establish the proper surgical approach to address the anticipated pathologies.

Anatomic Landmarks and Incisions

Standard, osseous, knee anatomy including patella, Gerdy’s tubercle, the fibular head, and medial and lateral joint lines are marked. Special care is taken to palpate and identify the peroneal nerve as it courses around the fibular neck. The dorsalis pedal pulse is palpated and marked for continual monitoring. The standard anterolateral arthroscopic portal is placed just adjacent to the lateral border of the patella tendon, above the joint line. The anteromedial portal is established at the same level, approximately 1 cm medial to the patellar tendon. Additionally, a superolateral outflow portal is established in standard fashion, superior to the patella and posterior to the quadriceps muscle. The posteromedial portal is often required to address the tibial insertion of the PCL, and it is established intraoperatively using an inside-out technique with the aid of a 70-degree arthroscope.

The operative incisions vary according to the structures that require repair. Our standard ACL/PCL tibial tunnel is marked 3 cm longitudinally over the anteromedial proximal tibia, 2 cm distal to the joint line and 2 cm medial to the tibial tubercle. The incision for the PCL femoral tunnel is marked 2 cm medial to the medial articular surface of the trochlea in the subvastus interval. If the injury has an associated medial component, the incision for the tibial tunnels is extended proximally in curvilinear fashion to the medial epicondyle. The incision

for lateral and posterolateral injuries is made, with the knee in flexion, in curvilinear fashion and extends proximally from the lateral epicondyle distally to a location midway between Gerdy’s tubercle and the fibular head (see Fig. 25.1) The proximal portion of this incision parallels the plane between the biceps femoris tendon and the iliotibial band. The skin incisions are injected preoperatively with 0.25% Marcaine with epinephrine (1:100,000).

for lateral and posterolateral injuries is made, with the knee in flexion, in curvilinear fashion and extends proximally from the lateral epicondyle distally to a location midway between Gerdy’s tubercle and the fibular head (see Fig. 25.1) The proximal portion of this incision parallels the plane between the biceps femoris tendon and the iliotibial band. The skin incisions are injected preoperatively with 0.25% Marcaine with epinephrine (1:100,000).

Graft Selection

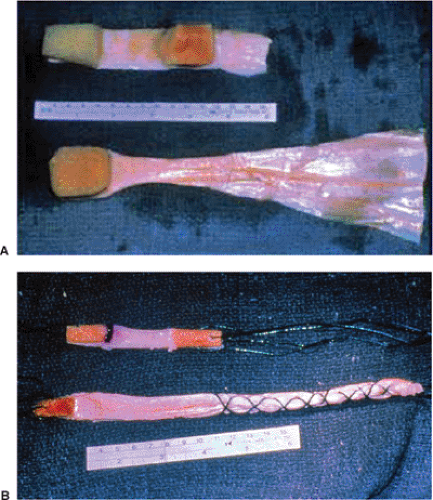

There are many options for graft selection in the knee injury involving multiple ligaments, most of which are surgeon dependent. The timing of surgery, extent of injury, experience of surgeon, and availability of allograft all factor into the selection process. The inherent advantages to autograft are offset in these complex cases by a choice of allograft, which will provide less donor-site morbidity and decreased operative time. For the ACL graft we currently prefer to use allograft bone-patellar tendon-bone graft. Soft-tissue allograft such as tibialis anterior is also a viable choice. For the PCL, we prefer to use Achilles tendon allograft because of its length, its girth, and the existence of the calcaneal bone plug for femoral fixation (Fig. 25.2). The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is usually reconstructed with an Achilles tendon allograft with a 7- to 8-mm calcaneal bone plug, which will be fixed in a proximal fibular-bone tunnel at the native LCL insertion site. The posterolateral corner is usually reconstructed with either a tibialis anterior allograft or a semitendinosus autograft.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy

To minimize the chance of compartment syndrome, we use gravity inflow irrigation with a superolateral outflow portal rather than a pump. The arthroscopic technique should be abandoned in favor of an open approach should extravasation be noted or a compartment syndrome suspected. A 30-degree arthroscope is introduced through the anterolateral portal and a diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to assess the integrity of the cruciate ligaments, the menisci, and the articular cartilage. A 70-degree scope is now placed through the anterolateral portal to establish the posteromedial portal, which will be used as the working portal for the tibial insertion of the PCL. Extreme caution should be exercised in this area to avoid extension of the debridement beyond the capsule and thus causing injury to the neurovascular structures, which reside approximately 1.5 cm posterior to the tibial insertion of the PCL. The use of the 30- and 70-degree arthroscopes through both the anterolateral and the posteromedial portal will allow for excellent access, visualization, and triangulization of the tibial PCL insertion site. Our attention is now turned to the ACL. We attempt to preserve as much of the ACL footprint as possible for vascular and pro-prioceptive considerations.

Next, we evaluate for any concomitant meniscal or articular cartilage injuries. Peripheral tears will be repaired using our preferred inside-out method, leaving the sutures to be secured with the knee in 30 degrees of flexion after all other grafts have been passed and secured. Central and irreparable tears are debrided back to a stable rim at this time.

Cruciate Tunnel Preparation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree