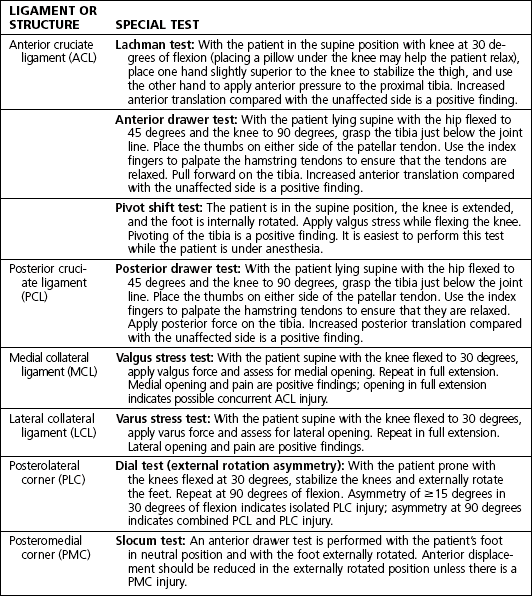

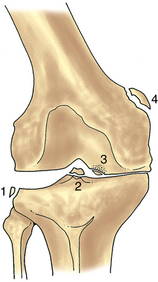

7 Knee and lower leg Table 7-1. Location and Function of Knee Ligaments Figure 7-2. Cross-sectional anatomy of the thigh and leg. Figure 7-4. Illustration showing multiple radiographic findings. 1, Segond fracture (lateral capsular sign); 2, tibial eminence fracture; 3, osteochondritis dissecans; 4, Pellegrini-Stieda lesion. (From Miller MD, Hart JA, MacKnight JM, editors: Essential orthopaedics, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.) Observe: gait (antalgic, assistive devices), alignment (valgus, varus), and feet (pes planus or cavus), ecchymosis, abrasion, gross deformity, effusion, quadriceps atrophy, and leg length discrepancy Palpate: quadriceps muscle and tendon, patella (all poles, tendon, and fat pads), medial collateral ligament (MCL) and medial joint line, lateral collateral ligament (LCL) and lateral joint line, bursa (prepatellar and infrapatellar, pes anserine), and popliteal fossa Normal range of motion (ROM): up to 10 degrees of hyperextension and 130 degrees of flexion Neurovascular examination (Table 7-4): assessment of sensation and motor function of the foot; palpation of dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial, and popliteal pulses; test of patellar reflex Table 7-4. Lower Extremity Neurologic Examination Figure 7-5. The Lachman examination. Note that the hand closest to the head of the patient grasps the thigh, and the opposite hand performs the examination with the thumb close to the joint line. A pillow can be placed under the knee to help the patient relax. (From Miller MD, Hart JA, MacKnight JM, editors: Essential orthopaedics, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.) Figure 7-6. The posterior drawer examination. Note that the starting point is evaluated by palpating the medial tibial plateau in relation to the medial femoral condyle before a posteriorly directed force is applied. (From Miller MD, Hart JA, MacKnight JM, editors: Essential orthopaedics, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.) Table 7-6. Differential Diagnosis Based on Location of Knee Pain LCL, lateral collateral ligament; MCL, medial collateral ligament; PLC, posterolateral corner. • Obtain standing flexion, lateral, and sunrise views. • Findings are often unremarkable; however, lateral tibial avulsion (Segond fracture) is highly suggestive of an ACL tear. Figure 7-7. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating (A) intact and (B) ruptured anterior cruciate ligament. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Estimated postoperative course • The patient may remove the wound dressing the second day after surgery and replace it with self-adhesive bandages, gauze, and an elastic compression (ACE) wrap. • Ice, elevation, and pain medication as needed (PRN) are indicated for comfort. • The patient uses a cane or crutches for the first few days for comfort. • Begin PT on postoperative day 1 or 2. Early-stage PT focuses on ROM, edema control, scar management, isometric quadriceps strengthening, and normalization of gait. • A wound check, suture removal, and assessment of ROM and stability are performed at 10 to 14 days postoperatively. • Obtain radiographs to assess tunnels and the position of the graft fixation device. • Evaluate healing of the surgical site, ROM, and stability of reconstruction. • Evaluate ROM and stability of reconstruction. • The patient may begin straight ahead running at 3 months under the guidance of a physical therapist or a certified athletic trainer (ATC). • The patient may return to sports at 6 months if able to pass functional testing with the ATC or the physical therapist. Figure 7-8. Positive posterior sag test. Note the position of the tibia (arrow). (From Miller MD, Hart JA, MacKnight JM, editors: Essential orthopaedics, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.) Figure 7-9. External rotation asymmetry. With the knees stabilized, both feet are passively externally rotated and the thigh-foot angle is measured. Asymmetry of 15 degrees or more implies injury to the posterolateral corner structures. The test is performed in both 30 degrees (A) and 90 degrees (B) of knee flexion. Asymmetry in both 30 and 90 degrees implies injury to both the posterolateral corner and the posterior cruciate ligament. (From Miller MD, Hart JA, MacKnight JM, editors: Essential orthopaedics, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.) Grade I: partial tear; posterior drawer demonstrating posterior tibial displacement that is anterior to the anterior aspect of the femoral condyles Grade II: posterior drawer demonstrating posterior tibial displacement that is flush with the anterior aspect of the femoral condyles Grade III: complete tear; posterior drawer demonstrating posterior tibial displacement posterior to the anterior aspect of the femoral condyles Figure 7-10. Posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A, The graft is passed from tibia to femur. B, Fixation is established with interference screws, and back-up fixation may be used if desired. (From Miller MD, Hart JA, editors: SMART: sports medicine assessment and review textbook, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders.) Transtibial single-bundle technique: Arthroscopic tibial inlay technique (single- or double-bundle): • Hinged brace locked in full extension at all times for 6 weeks. 50% weight bearing in brace with crutches to assist with ambulation, prone passive ROM with PT. • Remove the dressing on the second day after surgery, and replace it with gauze or self-adhesive bandages and an elastic compression (ACE) wrap. • Ice, elevation, and PRN pain medications are used for comfort. • A wound check, suture removal, and assessment of ROM and stability are performed at 10 to 14 days postoperatively. • The mechanism of injury is typically valgus stress to the knee. It can result from contact or noncontact injury. • Medial knee pain is present. • The patient is typically able to bear weight. • The patient may report a sensation of instability with pivoting. • Effusion may or may not be noted; localized swelling is more common. Figure 7-11. Varus stress testing. A varus stress is applied across the knee. This examination is done in both 30 degrees of knee flexion and full extension. Opening in full extension implies concurrent injury to the cruciate ligament. (From Miller MD, Hart JA, MacKnight JM, editors: Essential orthopaedics, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

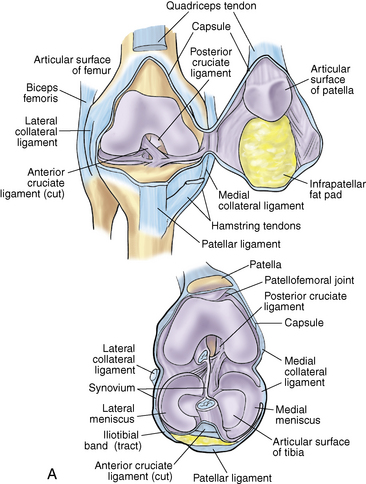

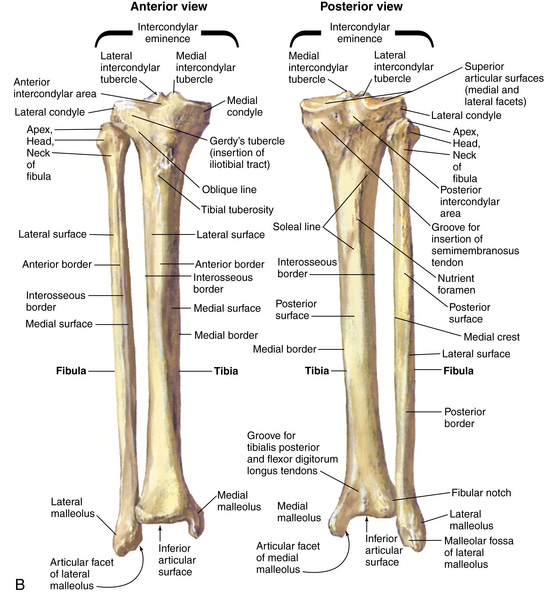

Anatomy

Ligaments: Table 7-1

LIGAMENT

LOCATION

FUNCTION

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

Originates on the tibia just anterior to the area between the tibial eminences and runs obliquely to the lateral femoral condyle

Primary restraint to anterior translation of the tibia; also rotational stability

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

Originates on lateral border of the medial femoral condyle and inserts on the posterior rim of the tibia

Primary restraint to posterior translation of the tibia

Medial collateral ligament (MCL)

Originates on the medial femoral epicondyle and inserts on the medial proximal tibia

Primary restraint to valgus force

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL)

Originates on the lateral femoral epicondyle and inserts on the anterolateral fibula

Primary restraint to varus stress

Posteromedial corner (PMC): posterior oblique ligament

Located deep and posterior to the MCL

Restraint to tibial internal rotation and valgus force

Posterolateral corner (PLC): biceps, iliotibial band, popliteus, popliteofibular ligament, and joint capsule

Located posterior to the LCL

Resistance to external rotation of the knee

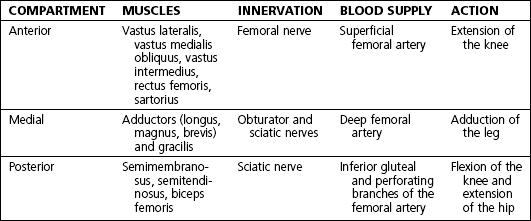

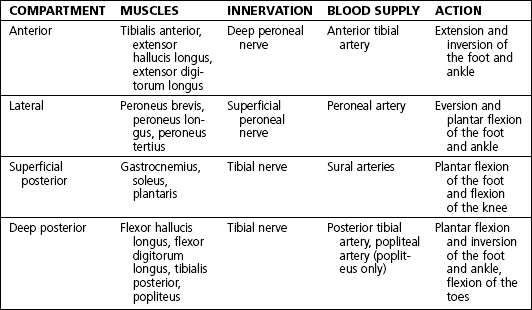

Muscles, nerves, and arteries: Figure 7-2 and tables 7-2 and 7-3

EDL, extensor digitorum longus; EHL, extensor hallucis longus; FDL, flexor digitorum longus; FHL, flexor hallucis longus. (From Miller MD, Hart JA, MacKnight JM, editors: Essential orthopaedics, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

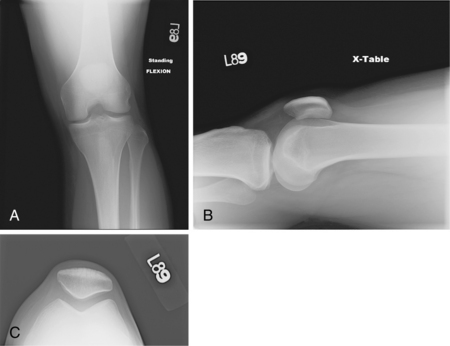

Normal radiographic appearance: Figures 7-3 and 7-4

Physical examination

NERVE

MOTOR FUNCTION

SENSORY DISTRIBUTION

Sural

Foot plantar flexion

Lateral heel

Saphenous

None

Medial leg and ankle

Superficial peroneal

Foot eversion

Dorsum of the foot

Deep peroneal

Great toe flexion

First web space

Tibial

Toe plantar flexion

Sole of the foot

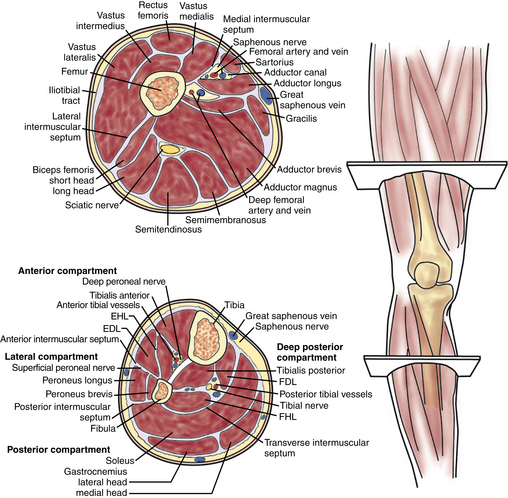

Special tests

Patellar apprehension test: The patient lies supine with the knee in 20 to 30 degrees of flexion and the quadriceps relaxed. Carefully glide the patella laterally. A positive test result is the presence of a reactive contraction of the quadriceps muscles by the patient in an attempt to avoid a recurrence of the dislocation or a sense of apprehension or fear that the patella will dislocate.

Patellar apprehension test: The patient lies supine with the knee in 20 to 30 degrees of flexion and the quadriceps relaxed. Carefully glide the patella laterally. A positive test result is the presence of a reactive contraction of the quadriceps muscles by the patient in an attempt to avoid a recurrence of the dislocation or a sense of apprehension or fear that the patella will dislocate.

Patellar grind test: The patient lies supine with knee fully extended. Push the patella distally in the trochlear groove. Have the patient tighten the quadriceps against patella resistance. Pain with or without crepitus is considered a positive test result.

Patellar grind test: The patient lies supine with knee fully extended. Push the patella distally in the trochlear groove. Have the patient tighten the quadriceps against patella resistance. Pain with or without crepitus is considered a positive test result.

Ligament examination: Table 7-5 and figures 7-5 and 7-6

Meniscal examination

McMurray test: With patient supine, take hold of the heel with one hand and flex the leg. Place the free hand on the knee with fingers along the medial joint line and the thumb and thenar eminence on the lateral joint line. Apply valgus force, and externally rotate the lower leg, and then maintain valgus force while internally rotating. A palpable or audible click is considered a positive finding.

McMurray test: With patient supine, take hold of the heel with one hand and flex the leg. Place the free hand on the knee with fingers along the medial joint line and the thumb and thenar eminence on the lateral joint line. Apply valgus force, and externally rotate the lower leg, and then maintain valgus force while internally rotating. A palpable or audible click is considered a positive finding.

Differential diagnosis: Table 7-6

The differential diagnosis for immediate effusion, in order of frequency, is as follows: anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear, patella dislocation, osteochondral fracture, and peripheral meniscus tear.

The differential diagnosis for immediate effusion, in order of frequency, is as follows: anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear, patella dislocation, osteochondral fracture, and peripheral meniscus tear.

LOCATION

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES

Anterior

Patellofemoral chondromalacia, prepatellar bursitis, patellar tendinitis, patellar fracture, patellofemoral osteoarthritis

Medial

Meniscus tear, MCL injury, osteoarthritis, pes anserine bursitis

Lateral

Meniscus tear, LCL injury, osteoarthritis, iliotibial band syndrome

Posterior

Tear of posterior horn of medial or lateral meniscus, neurovascular injury (popliteal artery or nerve), PLC injury

Anterior cruciate ligament injury

The mechanism is typically a noncontact pivoting injury.

The mechanism is typically a noncontact pivoting injury.

The patient often reports feeling or hearing a “pop” at the time of injury.

The patient often reports feeling or hearing a “pop” at the time of injury.

The patient is typically unable to continue activity or complete a sporting event.

The patient is typically unable to continue activity or complete a sporting event.

Instability with pivoting and swelling after activity are seen in chronic ACL tears.

Instability with pivoting and swelling after activity are seen in chronic ACL tears.

Physical examination

Observation: Note effusion, abrasion, and deformity.

Observation: Note effusion, abrasion, and deformity.

Palpation: Patellar ballottement is performed to assess for effusion. Joint line tenderness may be present secondary to concurrent meniscus tear.

Palpation: Patellar ballottement is performed to assess for effusion. Joint line tenderness may be present secondary to concurrent meniscus tear.

ROM: Decreased ROM may result from effusion. The lack of ability to extend the knee fully may occur with a concurrent displaced bucket handle meniscus tear.

ROM: Decreased ROM may result from effusion. The lack of ability to extend the knee fully may occur with a concurrent displaced bucket handle meniscus tear.

Special tests

Lachman, anterior drawer, and pivot shift tests

Lachman, anterior drawer, and pivot shift tests

Posterior drawer test to evaluate for posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

Posterior drawer test to evaluate for posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

McMurray test to evaluate for meniscus tear

McMurray test to evaluate for meniscus tear

Dial test to evaluate for posterolateral corner (PLC) injury

Dial test to evaluate for posterolateral corner (PLC) injury

Valgus and varus stress to evaluate the collateral ligaments

Valgus and varus stress to evaluate the collateral ligaments

Patella apprehension and patella glide tests to evaluate for possible patella dislocation

Patella apprehension and patella glide tests to evaluate for possible patella dislocation

Imaging

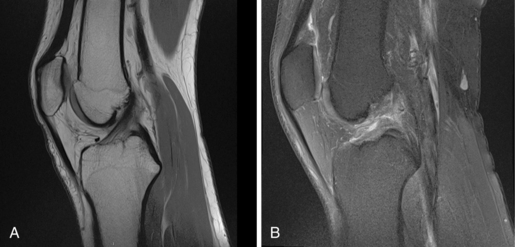

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee without contrast (Fig. 7-7)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee without contrast (Fig. 7-7)

Initial treatment

Treatment options, as well as the risks and benefits of all options, should be thoroughly reviewed and discussed with the patient.

Treatment options, as well as the risks and benefits of all options, should be thoroughly reviewed and discussed with the patient.

Graft selection for surgical reconstruction is made based on a variety of factors. In most cases, it is preferable to use a patient’s own tissue (autograft). Allograft (cadaveric tissue) is used when autograft is not available or to supplement inadequate autograft.

Graft selection for surgical reconstruction is made based on a variety of factors. In most cases, it is preferable to use a patient’s own tissue (autograft). Allograft (cadaveric tissue) is used when autograft is not available or to supplement inadequate autograft.

The most common sources of autograft are the hamstring tendons (typically gracilis and semitendinosus) or a bone patella tendon bone (BPTB) graft (central third of the inferior patella, patella tendon, and a small portion of the tibial tuberosity).

The most common sources of autograft are the hamstring tendons (typically gracilis and semitendinosus) or a bone patella tendon bone (BPTB) graft (central third of the inferior patella, patella tendon, and a small portion of the tibial tuberosity).

Treatment options

Conservative management may be appropriate for patients with a low activity level and less than 5 mm of laxity compared with the unaffected side.

Conservative management may be appropriate for patients with a low activity level and less than 5 mm of laxity compared with the unaffected side.

Physical therapy (PT) for ROM and quadriceps strengthening is indicated.

Physical therapy (PT) for ROM and quadriceps strengthening is indicated.

Without surgery, the patient may have recurrent instability and be at increased risk for meniscus tears and chondral injury or degeneration.

Without surgery, the patient may have recurrent instability and be at increased risk for meniscus tears and chondral injury or degeneration.

Operative management

Informed consent and counseling

Possible complications include instrument breakage, aberrant tunnels, cartilage injury, hardware failure, loss of motion, residual laxity, paresthesia, effusion, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and infection. Persistent anterior knee pain, patella tendon rupture, and patella fracture are potential complications if BPTB autograft is used.

Possible complications include instrument breakage, aberrant tunnels, cartilage injury, hardware failure, loss of motion, residual laxity, paresthesia, effusion, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and infection. Persistent anterior knee pain, patella tendon rupture, and patella fracture are potential complications if BPTB autograft is used.

Anesthesia risks include paralysis, cardiac arrest, brain damage, and death.

Anesthesia risks include paralysis, cardiac arrest, brain damage, and death.

Postoperative PT is essential to regain motion and return to sports or physical activities.

Postoperative PT is essential to regain motion and return to sports or physical activities.

Return to sports is usually not expected until 6 months postoperatively.

Return to sports is usually not expected until 6 months postoperatively.

Surgical procedures

Prepare and drape the lower extremity in a sterile fashion.

Prepare and drape the lower extremity in a sterile fashion.

Diagnostic arthroscopy is used to visualize the ACL and confirm injury, as well as to evaluate and treat meniscus tears, loose bodies, and chondral defects.

Diagnostic arthroscopy is used to visualize the ACL and confirm injury, as well as to evaluate and treat meniscus tears, loose bodies, and chondral defects.

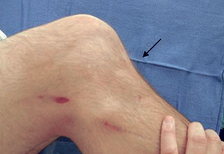

Graft harvesting: Techniques vary based on graft choice. A midline incision is made for BPTB graft, and a small oscillating saw is used to cut bone plugs from the patella and tibial tubercle. A medial vertical incision approximately 5 cm below the joint line is made for harvest of a hamstring graft. The semitendinosus and gracilis are identified and harvested with a tendon stripper.

Graft harvesting: Techniques vary based on graft choice. A midline incision is made for BPTB graft, and a small oscillating saw is used to cut bone plugs from the patella and tibial tubercle. A medial vertical incision approximately 5 cm below the joint line is made for harvest of a hamstring graft. The semitendinosus and gracilis are identified and harvested with a tendon stripper.

Graft preparation: This varies based on the graft source. All grafts should be handled carefully and are prepared by a qualified assistant at area separate from the operative field.

Graft preparation: This varies based on the graft source. All grafts should be handled carefully and are prepared by a qualified assistant at area separate from the operative field.

Débridement and notchplasty: Excess fibrous tissue and the ACL stump are débrided with a motorized shaver and bur to allow for better visualization of the back of the notch and to provide clearance for the graft.

Débridement and notchplasty: Excess fibrous tissue and the ACL stump are débrided with a motorized shaver and bur to allow for better visualization of the back of the notch and to provide clearance for the graft.

Tunnel placement: The technique for tibial and femoral tunnel placement is determined by the surgeon’s preference. The goal is to recreate the normal anatomic position of the ACL.

Tunnel placement: The technique for tibial and femoral tunnel placement is determined by the surgeon’s preference. The goal is to recreate the normal anatomic position of the ACL.

Graft passage: Sutures that are attached to both ends of the graft are passed through the tunnels.

Graft passage: Sutures that are attached to both ends of the graft are passed through the tunnels.

Graft fixation: If BPTB graft is used, the graft is fixed with interference screws. For hamstring graft, an implant designed for soft tissue fixation is used.

Graft fixation: If BPTB graft is used, the graft is fixed with interference screws. For hamstring graft, an implant designed for soft tissue fixation is used.

Wound closure: Multilayer closure is augmented with Steri-Strips; then a sterile dressing and an elastic compression (ACE) wrap are applied.

Wound closure: Multilayer closure is augmented with Steri-Strips; then a sterile dressing and an elastic compression (ACE) wrap are applied.

Postoperative day 0 to 6 weeks

Postoperative day 0 to 6 weeks

Postoperative 6 weeks to 3 months

Postoperative 6 weeks to 3 months

Posterior cruciate ligament injury

The mechanism of injury is typically a blow to the anterior tibia (i.e., dashboard injury) or a fall on a plantar flexed foot. Hyperextension or hyperflexion injuries also lead to PCL tear.

The mechanism of injury is typically a blow to the anterior tibia (i.e., dashboard injury) or a fall on a plantar flexed foot. Hyperextension or hyperflexion injuries also lead to PCL tear.

Frank instability may or may not be present.

Frank instability may or may not be present.

Anterior and medial knee pain may be reported in chronic injury.

Anterior and medial knee pain may be reported in chronic injury.

Isolated PCL rupture is rare; it more commonly occurs in the multiligament knee injury.

Isolated PCL rupture is rare; it more commonly occurs in the multiligament knee injury.

Physical examination

Observation: Note effusion, ecchymosis, abrasion, and obvious deformity.

Observation: Note effusion, ecchymosis, abrasion, and obvious deformity.

Palpation: Patellar ballottement is performed to assess for effusion. Joint line tenderness may be present because of concurrent meniscus tear.

Palpation: Patellar ballottement is performed to assess for effusion. Joint line tenderness may be present because of concurrent meniscus tear.

Special tests: Figures 7-8 and 7-9

Posterior drawer test: See the classification section.

Posterior drawer test: See the classification section.

Posterior sag test: With the knee and hip at 90 degrees of flexion, look for posterior sag of the tibia.

Posterior sag test: With the knee and hip at 90 degrees of flexion, look for posterior sag of the tibia.

Dial test: This is used to assess the PLC.

Dial test: This is used to assess the PLC.

Complete a thorough knee examination to rule out other ligamentous, meniscal, or patellar disorders.

Complete a thorough knee examination to rule out other ligamentous, meniscal, or patellar disorders.

Imaging

Radiographs: Standing flexion, lateral, and sunrise views are often unremarkable, but they may show a PCL avulsion fragment. Stress views are obtained by applying posterior force to the proximal tibia with a Telos device.

Radiographs: Standing flexion, lateral, and sunrise views are often unremarkable, but they may show a PCL avulsion fragment. Stress views are obtained by applying posterior force to the proximal tibia with a Telos device.

MRI: Imaging helps to identify the degree of injury (partial versus complete tear) and associated ligament, meniscus, and chondral injuries.

MRI: Imaging helps to identify the degree of injury (partial versus complete tear) and associated ligament, meniscus, and chondral injuries.

Classification

Classification is based in the degree of posterior subluxation of the tibia in relation to the femoral condyles:

Classification is based in the degree of posterior subluxation of the tibia in relation to the femoral condyles:

Initial treatment

Unlike the ACL, the PCL has some healing potential.

Unlike the ACL, the PCL has some healing potential.

Not all PCL injuries require surgical reconstruction. Nonoperative management consists of intensive PT.

Not all PCL injuries require surgical reconstruction. Nonoperative management consists of intensive PT.

Some research indicates an increased risk of developing degenerative changes in the PCL-deficient knee, especially in the patellofemoral compartment.

Some research indicates an increased risk of developing degenerative changes in the PCL-deficient knee, especially in the patellofemoral compartment.

Treatment options

Operative management

Informed consent and counseling

Possible complications include residual laxity, instrument breakage, aberrant tunnels, avascular necrosis of the medial femoral condyle, cartilage injury, heterotopic ossification, hardware failure, loss of motion, neurovascular injury, paresthesia, effusion, DVT, and infection. Anesthesia risks include paralysis, cardiac arrest, brain damage, and death.

Possible complications include residual laxity, instrument breakage, aberrant tunnels, avascular necrosis of the medial femoral condyle, cartilage injury, heterotopic ossification, hardware failure, loss of motion, neurovascular injury, paresthesia, effusion, DVT, and infection. Anesthesia risks include paralysis, cardiac arrest, brain damage, and death.

Postoperative PT is essential to regain full ROM, strengthen quadriceps, and return to sport or physical activities.

Postoperative PT is essential to regain full ROM, strengthen quadriceps, and return to sport or physical activities.

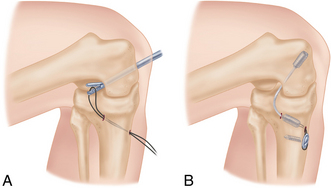

Surgical procedure: Figure 7-10

Autograft (patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon, or hamstring tendons) or allograft (patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon, Achilles tendon, and hamstring tendons) may be used.

Autograft (patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon, or hamstring tendons) or allograft (patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon, Achilles tendon, and hamstring tendons) may be used.

The extremity is prepared and draped in standard sterile fashion. The tibial tunnel is drilled at the anterolateral cortex of the proximal tibia. The knee is flexed to 110 degrees while the proximal tibia is pushed in posteriorly. A plastic sheath is placed in contact with the lateral femoral condyle, and then a femoral tunnel is created 2 to 3 mm proximal to the articular junction at the 1 o’clock position in the right knee or the 11 o’clock position in the left. A fixation device (chosen based on surgeon preference) is attached to the graft with a whipstitch. The graft is passed through both tunnels and secured with interference screws. The incisions are irrigated, then closed, and a sterile dressing is applied.

The extremity is prepared and draped in standard sterile fashion. The tibial tunnel is drilled at the anterolateral cortex of the proximal tibia. The knee is flexed to 110 degrees while the proximal tibia is pushed in posteriorly. A plastic sheath is placed in contact with the lateral femoral condyle, and then a femoral tunnel is created 2 to 3 mm proximal to the articular junction at the 1 o’clock position in the right knee or the 11 o’clock position in the left. A fixation device (chosen based on surgeon preference) is attached to the graft with a whipstitch. The graft is passed through both tunnels and secured with interference screws. The incisions are irrigated, then closed, and a sterile dressing is applied.

The extremity is prepared and draped in standard sterile fashion. Anterolateral and anteromedial portals are established. Diagnostic arthroscopy is performed; meniscal and cartilage disorders are addressed. Next, a posteromedial portal is established for instrument passage. The PCL stump is débrided, while preserving the anterior edge of the PCL footprint to serve as a reference point for the inlay. The tibial tunnel is prepared with the knee in flexion. An arthroscopic PCL guide is used to position a pin in the proximal aspect of the PCL footprint. A flip cutter is used to create the tibial socket in an inside-out fashion. A C-arm and the arthroscope are used for guidance. The femoral tunnels are created using a PCL guide centered over the medial femoral condyle at the border of the vastus medialis. For single-bundle reconstruction, the femoral tunnel is drilled at the 11 o’clock position; for double-bundle reconstruction, tunnels are drilled at 9 o’clock and 11 o’clock positions. Grafts are passed with the knee flexed at 90 degrees. The grafts are fixed (various fixation devices are available). The incisions are irrigated, then closed, and a sterile dressing is applied.

The extremity is prepared and draped in standard sterile fashion. Anterolateral and anteromedial portals are established. Diagnostic arthroscopy is performed; meniscal and cartilage disorders are addressed. Next, a posteromedial portal is established for instrument passage. The PCL stump is débrided, while preserving the anterior edge of the PCL footprint to serve as a reference point for the inlay. The tibial tunnel is prepared with the knee in flexion. An arthroscopic PCL guide is used to position a pin in the proximal aspect of the PCL footprint. A flip cutter is used to create the tibial socket in an inside-out fashion. A C-arm and the arthroscope are used for guidance. The femoral tunnels are created using a PCL guide centered over the medial femoral condyle at the border of the vastus medialis. For single-bundle reconstruction, the femoral tunnel is drilled at the 11 o’clock position; for double-bundle reconstruction, tunnels are drilled at 9 o’clock and 11 o’clock positions. Grafts are passed with the knee flexed at 90 degrees. The grafts are fixed (various fixation devices are available). The incisions are irrigated, then closed, and a sterile dressing is applied.

Estimated postoperative course

Postoperative day 0 to 6 weeks

Postoperative day 0 to 6 weeks

Postoperative 6 weeks to 3 months

Postoperative 6 weeks to 3 months

Medial collateral ligament injury

Physical examination

Observation: Note effusion, ecchymosis, deformity, abrasion or contusion, and gait.

Observation: Note effusion, ecchymosis, deformity, abrasion or contusion, and gait.

Palpation: Palpate the entire course of the MCL, from proximal to distal. Tenderness typically indicates some degree of MCL injury. Joint line tenderness is indicative of concomitant meniscus tear. Lateral tenderness of the distal femur and proximal tibia may result from bony contusion.

Palpation: Palpate the entire course of the MCL, from proximal to distal. Tenderness typically indicates some degree of MCL injury. Joint line tenderness is indicative of concomitant meniscus tear. Lateral tenderness of the distal femur and proximal tibia may result from bony contusion.

Special tests: Figure 7-11

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Knee and lower leg