Jaundice (Case 25)

Austin Hwang MD and Giancarlo Mercogliano MD, MBA, AGA

Case: A 60-year-old man presents with jaundice, 20-pound weight loss, intermittent nausea, and decreased appetite over the last month. He has a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. There is no past surgical history. He takes hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, and metformin. His BP, cholesterol, and diabetes are under good control. He has drunk three beers each day and smoked half a pack of cigarettes per day for the last 40 years. He has no abdominal pain, but he has noticed that his stools have become lighter in color and his urine has become tea-colored. He presents in the outpatient office accompanied by his wife and three of his children, who have urged him to seek medical attention.

Differential Diagnosis

Hepatocellular Causes | Extrahepatic/Obstructive Causes |

Viral hepatitis | Choledocholithiasis |

Alcoholic hepatitis | Cholangitis |

Drug-induced hepatitis | Benign stricture |

Cirrhosis | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma |

Speaking Intelligently

When asked to see an older patient with jaundice, we worry about cancer. A helpful start in patients with this clinical presentation is to decide whether the cause is hepatocellular or obstructive. These two categories serve as a useful framework to think about elevated serum bilirubin levels. Treatment of hepatocellular causes is generally supportive, while treatment of obstructive causes is with endoscopy or surgery. History taking allows me to create a diagnostic hypothesis. Laboratory values and imaging help me to corroborate this hypothesis. Liver function tests (LFTs) are crucial. Ultrasonography evaluates the hepatic parenchyma and biliary ducts.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• Use LFTs and imaging (ultrasound, CT, MRI) to help corroborate your hypothesis.

• Pattern recognition of LFTs aids in diagnosis. Please see below.

History

• History of associated pain or lack of pain is important.

• Past medical history is important: History of gallstones (choledocholithiasis), colon cancer (liver metastases), or chronic pancreatitis (bile duct strictures).

Physical Examination

• In the presence of fever, think cholangitis.

Tests for Consideration

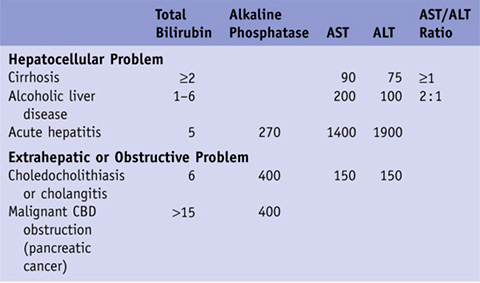

Table 32-1 Typical Laboratory Values*

*For clarity, we have chosen typical values that are representative of each condition. Those fields that are empty are either too variable to quantify or not useful as diagnostic guides.

CBD, common bile duct.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree