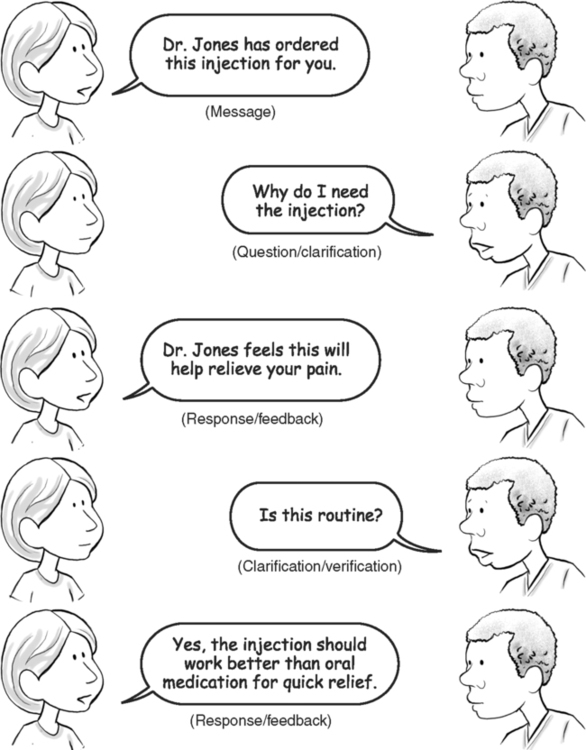

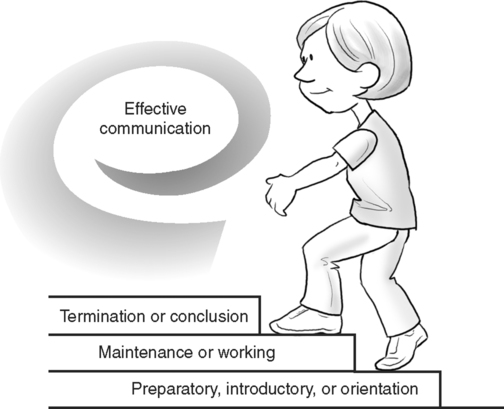

Upon successful completion of this chapter, you will be able to: • Describe the steps in effective communication. • List your responsibilities in the communication process. • List the patient’s responsibilities in the communication process. • Differentiate between verbal and nonverbal communication. • Explain how nonverbal communication can affect the interpretation of verbal messages. • Describe ways to determine when touch is welcome or appropriate. • List ways to establish and maintain rapport with patients. The information you receive while talking with patients must be transmitted accurately, appropriately, and confidentially (Box 1-1) to physicians and other professional staff members. You must also translate information from physicians and other staff members in a manner that patients can understand. A positive attitude, pleasant presentation, and good communication skills establishrapport, a relationship of trust and understanding, for future interactions with patients. These skills also help maintain the flow of communication back and forth between health care professionals. • A message to be transmitted in a form understandable to the receiver • A sender, usually a person, to transmit the message • A method for transmitting the message—verbal, nonverbal, or written • A ready and receptive receiver to accept the message • Clarification or verification that the message was received and understood The channel or method of transmitting the message may be either spoken or written, it may be body language, or it may be a simple facial expression. We have all transmitted messages to someone across a room using only significant looks and body language. For the message to be transmitted effectively, the receiver must be ready and able to accept it. This is like sending a fax if the receiving machine is not on. If the patient is not ready to accept the message, or cannot receive it because of her physical or emotional state, her “receiver” is not on. In Chapter 2, “Challenges to Communication,” we cover how to determine when the patient is “ready to receive” and how to communicate if he is not ready but you need to talk with him about his health care at the time. When the message is in the verbal or spoken form, the sender and receiver alternate roles as they transmit their part of the information needed in the exchange and look for responses in the form of feedback and verification. The process of message exchange is like a tennis match, with the message, like a ball, passing from person to person. Figure 1-1 illustrates the flow of oral communication and its common components. Communication is conducted in steps (Fig. 1-2). The first is the preparatory, introductory, or orientation step. This step introduces the participants to each other and helps form a mutual agreement to exchange information. Roles and responsibilities are established within the first few moments, usually by implied agreement. There is usually no formal agreement that each participant will perform certain functions in the exchange, but by founding the relationship, each participant agrees to fulfill his or her part of the exchange until the situation is resolved or the interaction comes to an end. For example, if a patient makes a health care request that you can help resolve, the guidelines are implied that she will give you all of the information you need to help her. By coming to her aid, you imply that you will do everything reasonable to fill her needs. The two of you have reached an informal agreement, which completes the introductory phase. The second step is the working, or maintenance, step. The conversation is focused on the task at hand and works to meet the needs of each participant. Each participant observes the responses of the other for communication cues (covered later in this chapter) to determine that all messages are properly received. The health care worker usually directs, or leads, the interaction but should not control it. It is your responsibility to keep the exchange on track—to keep the patient from rambling—but controlling the flow interrupts the free and open exchange needed to determine all of the patient’s needs. Today, he may need to talk about his personal problems rather than participate in an intense and comprehensive health history, and you must respect that need. Helping him talk about his problems may be as therapeutic as any clinical procedure you may perform, but gentle, tactful, probing questions (covered in Chapter 3, “Gathering Information”) may help guide him back on track to direct the conversation toward his immediate health care needs. The final step is the termination or conclusion. If the exchange was effective and successful, each party is satisfied that messages were transmitted and received as intended. (Guidelines to help overcome a breakdown in communication are covered in Chapter 2, “Challenges to Communication”). At the conclusion of the exchange, goals should be reached, such as determining the patient’s current need for care, or, if you are working in an intermediate position, the relationship is transferred to another worker. The relationship may be as short-term as greeting patients for a one-time visit, or may be an established relationship for long-term, chronic care. In either case, or in any health care situation, the dynamics of communication—how communication works—and the need for exchange remain the same. All of the steps listed above are involved in any exchange, from a brief conversation as you greet your patients to a complicated transfer of complex medical information over an extended period. If the relationship is long-term, well-established, and pleasant for both the patient and you, at its eventual end you may feel a sense of loss, but you should also feel pride in the independence and growth you have helped your patient achieve. Before you can communicate effectively with anyone else, you must first communicate with yourself and understand who you are. Every culture, every age, every person you come in contact with will sense whether you genuinely care for his or her welfare, or if your interest is insincere. Box 1-2 outlines a number of questions to ask yourself to help determine whether you are ready for the demands of health care. When you can answer these questions honestly and selflessly, you have reached a level of self-awareness that puts the patient’s needs before your own. • Be familiar with the patient’s history and current condition to determine what information is needed with the background already available. You need answers to questions such as: Is this simply an annual examination, or is the visit in response to a life-threatening situation? How ill is the patient now? Is he too sick for effective communication? • Check the patient’s history for possible barriers to communication, such as English as a second language, hearing impairment, and so on. Do you need an interpreter? Do you need a notepad for a written exchange? • Be aware of the patient’s communication needs. Use common sense and good judgment. Does she need to talk today to relieve stress and anxiety, or is a casual conversation enough for today? Is superficial chatter a cover for more important information? If so, can you determine what she is trying not to tell you? • Demonstrate courtesy and compassion. Even a brief encounter requires good manners and a caring attitude. • Remain objective regarding personal and cultural differences. It is not necessary to agree with patients to understand their needs or to provide excellent care. Use your personal differences as a learning opportunity. • Clarify the message for understanding. Did the patient say what you thought he said? Did he understand what you said? Ask or answer as many questions as needed for clarification. • Validate the patient’s feelings. She has a right to feel as she does: sad, angry, frightened, and so forth. • Phrase your message so that patients can understand. Are you using terms above or below the patient’s understanding? Are you trying to interact professionally, or are you trying to impress? • Encourage good health care choices and independent care. It is our goal to turn the patient’s care over to him when he is able. Did you use every opportunity to educate him in proper wellness measures? • Provide feedback and ask for it in return to be sure the messages were clearly received. Can the patient repeat your instructions satisfactorily and demonstrate understanding? Did you understand what she was trying to tell you? • Provide learning tools, such as pamphlets or written instructions for self-care, and be sure they are designed for the patient’s needs (see Chapter 4, “Educating Patients”).

INTRODUCTION TO COMMUNICATION: BUILDING THE FRAMEWORK

INTRODUCTION TO COMMUNICATION: BUILDING THE FRAMEWORK

HOW COMMUNICATION WORKS

Steps in the Communication Process

Your Responsibility to the Patient

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

INTRODUCTION TO COMMUNICATION: BUILDING THE FRAMEWORK

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue