Chapter 1

Introduction and Overview

Upon completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

1. Define assistive technology

2. Delineate the characteristics of assistive technologies

3. Describe the components of the assistive technology industry

4. Explain the roles of the consumer

5. Identify several distinguishing features of service delivery programs

6. Identify the roles of those who are associated with the provision of assistive technologies

7. Understand the transdisciplinary approach to assistive technology service delivery

8. Discuss the major professional issues in assistive technology practice

Much of the information available about assistive technologies is intended for those individuals who are assessing and recommending these technologies.3 There is much less written for the person who is responsible for implementing these recommendations and making assistive technologies work to meet the needs of people who have disabilities. This book has been written to support those front line rehabilitation therapy workers who need basic information about assistive technologies with an emphasis on implementing effective systems in clinical and community settings. We begin in this chapter by providing an overview of assistive technologies and the industry that supports their development and distribution. We also discuss standards of practice in assistive technology and a code of ethics for practitioners.

Assistive technologies: a working definition

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) is a system developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) that is designed to describe and classify health and health-related states. These two domains are described by body factors (body structures and functions) and individual and societal elements (activities and participation).19 The ICF is a revision of the previous classification system, the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH).18 Two primary shifts in philosophy discriminate between the ICIDH and the ICF classification systems: the recognition of the importance of the environment as a mediating factor in the performance of daily function, and the use of more positive language.

Body structures and function refer to the structural and physiological functions of the body. For example, the classification relating to vision lists the anatomical structures of the eye and the sensory and motor as well as perceptual elements of vision. Activity and participation are considered to be a single classification. There is much debate on whether it is possible to differentiate between an activity and participation. Something that may be considered participation at one stage in life becomes an activity at a later stage. The ICF defines activities as the “execution of tasks” and participation as “involvement in life situations.”19 Examples of the different components of activity and participation include learning and applying knowledge, communication, mobility, self-care, and community, social, and civic life.

The ICF recognizes two contextual factors that modify health and health-related states: the environment and personal factors.19 The latter are not classified but merely identified and include age, gender, race, lifestyle habits, and social and cultural backgrounds, among other factors. The inclusion of these factors in the ICF recognizes their ability to differentially influence the outcome of the same impairment in two individuals.

The ICF does classify environmental elements. Assistive technologies are located in this classification, most prominently in the products and technology chapter. They are specifically mentioned related to activities of daily living, mobility, communication, religion, and spirituality as well as in specific contexts such as education, employment, culture, recreation, and sport.19 Many of the remaining environmental chapters have reference to assistive technology, although it is not mentioned explicitly. These chapters include access to public and private buildings; the natural and built outdoor environments; people and animals that provide physical and emotional support (personal care attendants and health care professionals are identified here, service animals are not); attitudes of individuals and others; and services, systems, and policies, including legislation.19 Scherer and Glueckauf (2005)13 reviewed the ICF and discussed the implications to assistive technology provision. They concluded that the revised classification system puts the onus on the assistive technology provider to demonstrate positive outcomes for assistive technology recommendations and use.

Definition of Assistive Technology Devices and Services

Dictionaries provide the following definition of “technology”:

(1) The science or study of the practical or industrial arts, (2) applied science, (3) a method, process, etc., for handling a specific technical problem.6,8 Surprisingly, none of these definitions says anything about a “device”; instead the emphasis is on the application of knowledge. This is an important concept, and we shall use the term assistive technology (AT) to refer to a broad range of devices, services, strategies, and practices that are conceived and applied to ameliorate the problems faced by individuals who have disabilities.

Characterization of Assistive Technologies

In this section we present a characterization of assistive technologies from several points of view. Each of these is a logical outgrowth of the definitions presented earlier, and each is useful in the process of applying assistive technologies. Box 1-1 shows several classifications used to distinguish different types of assistive technologies.

Assistive versus Rehabilitative or Educational Technologies

Technology can serve two major purposes: helping and teaching.15 Technology that helps an individual to carry out a functional activity is termed assistive technology. Our emphasis in this text is on assistive technologies that serve a variety of functional needs. Technology can also be used as part of an educational or rehabilitative process. In this case the technology is usually used as one modality in an overall education or rehabilitation plan. Technology in this sense is used as a tool for remediation or rehabilitation rather than being a part of the person’s daily life and functional activities, and we refer to it as rehabilitative or educational technology, depending on the setting. Often rehabilitative or educational technology (e.g., cognitive retraining software) is employed to develop skills for the use of assistive technologies. We discuss some of these applications in later chapters.

Hard and Soft Technologies

Odor (1984)11 has distinguished between hard technologies and soft technologies. Hard technologies are readily available components that can be purchased and assembled into assistive technology systems. This includes everything from simple mouth sticks to computers and software. The PL 100-407 definition of an assistive technology device applies primarily to hard technologies as we have defined them. The main distinguishing feature of hard technologies is that they are tangible. On the other hand, soft technologies are the human areas of decision making, strategies, training, concept formation, and service delivery as described earlier in this chapter. Soft technologies are generally captured in one of three forms: (1) people, (2) written, and (3) computer software.1 Assistive technology services as defined in PL 100-407 are basically soft technologies. These aspects of technology, without which the hard technology cannot be successful, are much harder to obtain because they are highly dependent on human knowledge rather than tangible objects. This knowledge is obtained slowly through formal training, experience, and textbooks such as this one. The development of effective strategies of use also has a major effect on assistive technology system success. Initially the formulation of these strategies may rely heavily on the knowledge, experience, and ingenuity of the assistive technology practitioner. With growing experience, the assistive technology user originates strategies that facilitate successful device use. The roles of both hard and soft technologies as integral portions of assistive technology systems are discussed in later chapters.

Appliances versus Tools

An appliance is a device that “provides benefits to the individual independent of the individual’s skill level.”16 Tools, on the other hand, require the development of skill for their use. Household appliances such as refrigerators do not require any skill to operate, whereas tools such as a hammer or saw do require skill. The determining factor in distinguishing a tool from an appliance is that the quality of the result obtained using a tool depends on the skill of the user. For example, eyeglasses or a seating system are appliances since the quality of the functional outcome does not depend on the skill of the user. Success in maneuvering a powered wheelchair or generating a meaningful utterance with an augmentative communication system does depend on the skill of the user, and these are classified as tools. Examples of assistive technology tools and appliances are shown in Table 1-1.

Table 1-1

Examples of Assistive Technology Tools and Appliances

| Topic (Chapter) | Appliances | Tools |

| Control interfaces (6) | Keyguards | Joystick |

| Computer access (7) | Enlarging lens | Enlarged keyboard |

| Augmentative communication (11) | — | Alphabet board |

| Manipulation (14) | Environmental control* | Electric feeder |

| Mobility (12) | Wheelchair armrest | Manual wheelchair push rims |

| Sensory (8) | Eyeglasses | Long cane |

*See text; classification depends on EADL (electronic aid for daily living) and its functions.

As Vanderheiden (1987)16 points out, the successful use of assistive technology tools requires training, strategies, and special skills. These are soft technologies. Tools require carefully planned and implemented training programs that lead to skill development. Some appliances may also require training of care providers and the user of the technology. For example, when a new seating system (an assistive technology appliance) is provided (Chapter 4), the care staff must be trained in how to position the person in the seating system and how to position the system in the wheelchair.

People routinely use observation, such as watching someone using a hammer, as a means of learning how to use a tool. Because tools used by persons with disabilities are often different from those used by the general population, the assistive technology user often cannot observe someone using the same device, and she must rely more heavily on personal experience and training to learn to use it effectively.16 The importance of strategies and skills for assistive device use means that the trainer, most often a rehabilitation assistant such as an occupational therapy assistant (OTA), physical therapy assistant (PTA) and speech language pathology assistant (SLPA) has a large role in the ultimate success of the assistive technology system.

Commercial to Custom Technology

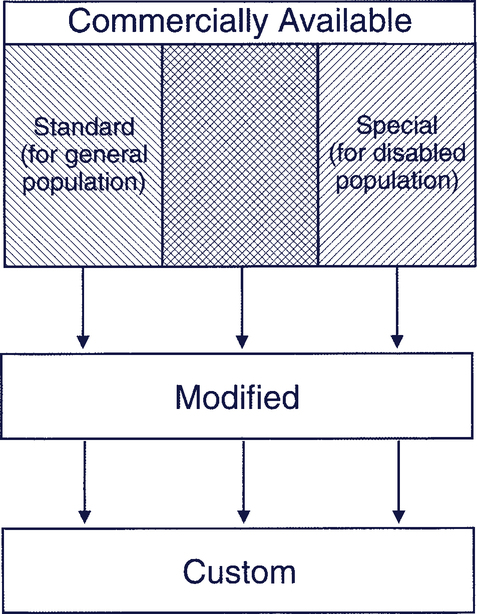

For many applications, mainstream technologies (computers, mobile phones, tablet computers) with an assistive technology software application are being used to meet the needs of individuals with disabilities. When mainstream devices cannot meet the needs directly, they may be able to be modified to fit the assistive technology application. In many cases, however, the mainstream technology, modified or not, cannot meet the needs and a specially designed assistive technology is required. Many assistive technologies are mass produced and available commercially. We use the term commercially available to refer to devices that are mass produced. Commercially produced devices (mainstream and assistive technologies) can generally meet the majority of needs that people with disabilities face. In some cases, however, it is necessary to design and build a completely custom device because no commercially available approach will work. Figure 1-1 illustrates the progression from commercially available devices to those that are completely customized for an individual.

Universal Design

Universal design is the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.10 The product design includes use of universal design features that make a product more useful to persons who have disabilities. Typical features that are addressed include: larger knobs; a variety of display options—visual, tactile, and auditory; and alternatives to reading text such as icons and pictures. This is much less expensive than modifying a product after production to meet the needs of a person with a disability. In some countries, universal design is known as “design for all.” A set of universal design principles is shown in Box 1-2.*

Commercial Assistive Technologies

When an individual’s needs for assistive technology cannot be met with a commercial device, we attempt to use mass-produced, commercially available devices that are designed for people with disabilities. Examples include wheelchairs, augmentative communication systems, and many aids to daily living. In some cases a combination of standard and special-purpose technologies is used; this is represented by the crosshatched area of Figure 1-1. For example, a standard general-purpose computer or smart phone may be used with special-purpose software to create an augmentative communication device (see Chapter 11).

Custom Devices

When no commercial device or modification is able to meet the need, it is necessary to design and build a device specifically for the task at hand. This approach results in a custom device. One example of such a device is the jigs used for cognitive aids such as the one shown in Chapter 10, Figure 10-8. Because the production demands are unique, the jigs must be custom made. Custom devices can be expensive because they are often made for just one person. An important difference between modified or custom devices and commercial devices is the level of technical support that is available. There are sometime volunteers (e.g., retired engineers or electronics technicians) who can make a custom device. A word of caution, however, is that once the device is made the person often disappears, leaving the front line person to repair and maintain the device. Custom devices can also be of lesser quality than commercial devices. The initial lower cost (e.g., of switches) rarely pays off in the long run because custom devices must be replaced far more frequently. A commercially produced device generally has written documentation and operator’s manuals available. Modified or custom devices often have little or no written documentation. The manufacturer or supplier of commercial equipment provides technical support and repair. Because modified or custom devices are one of a kind, technical support may be hard to obtain, especially if the original designer and builder is no longer available (e.g., if the user moves to a new area).

The assistive technology industry

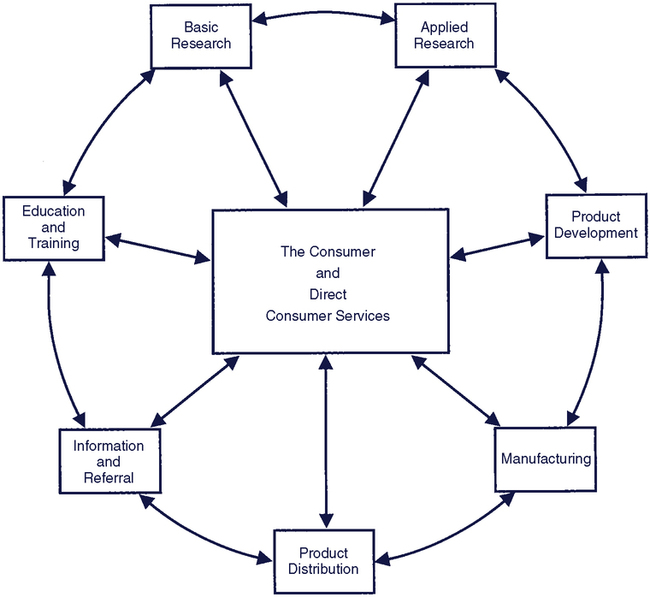

Figure 1-2 depicts the components of the assistive technology industry and how they are interrelated. Each component in this figure plays an important role in making assistive technologies available to people who have disabilities.

The Consumer and Direct Consumer Services

All the components in Figure 1-2 are focused on the consumer who uses the assistive technology devices and services. The key component linking the consumer to the other components is the delivery system that actually provides the technology to the consumer. Thus, the consumer and direct consumer services are at the center of the figure. However, it is important to note that it is desirable for the consumer to be involved in all aspects of the industry. Direct consumer services is the component in which a consumer’s need for assistive technology is identified, an evaluation is completed, recommendations are made, and the system is implemented. Implementation includes setting up an assistive technology system, training the consumer and support personnel in its use, and following the consumer’s progress with the system to make sure that it meets his or her needs.

The Consumer

The consumer of assistive technologies is the recipient, or end user, of assistive technology, and all of the industry components should be responsive to the consumer’s needs. The true test of effectiveness of assistive technologies is the consumer use of the device in the “real world” outside of the clinic. This use will produce information from the consumer and direct service providers that can impact the other components of Figure 1-2 so that improvements in products and services can be made. The other components also affect the consumer and the direct consumer service providers through research, new product development, and dissemination of information.

The consumer is not, however, solely the recipient of the technology. The consumer must be considered an active participant in the other industry components in order for them to be effective. White et al. (2004)20 describe the process of participatory action research in assistive technology wherein the consumer is involved in all aspects of assistive technology research, development, and implementation.

Because they use assistive devices regularly, consumers are the experts in the use of assistive technologies. They develop skills that exceed those of support personnel, and they can be effective as mentors to others by demonstrating how to effectively use a particular device. The Empowering End Users Through Assistive Technology (EUSTAT) project in Europe has developed guidelines for trainers, a set of critical factors for assistive technology training, and descriptive information on programs that provide assistive technology training for consumers (http://www.siva.it/research/eustat/download_eng.html). One of the documents developed by EUSTAT is written for consumers of AT services and gives practical guidance regarding how to access these services. As you read about each component of the assistive technology industry, think about ways in which consumers can be involved.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree