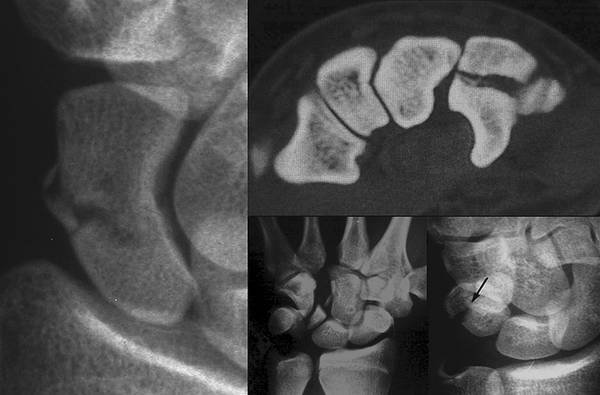

The literature on the management of the articular injury of the wrist is extensive. Since the year 2000, more than a thousand peer-reviewed articles on the topic have been published; yet, numerous questions remain unsolved. For instance, the once-unquestioned principle that even a suboptimally reduced fracture tends to do well if solidly fixed and mobilized early has repeatedly been challenged.1 The use of external fixators to neutralize the destabilizing forces across an unstable fracture, once common, is now seldom practiced. Not long ago, several treatment options were considered for a distal radial fracture; now there is only one: volar plate fixation. Has the pendulum swung too far?2 To shed some light on these controversies, an instructional course entitled “Articular Injury of the Wrist” has been organized for the 2014 FESSH meeting in Paris. Twenty-seven European experts have been invited to propose guidelines to manage these complex conditions. This book, truly a summary of what will be discussed in Paris, may be of interest to those who are regularly confronted with this peculiar type of injury. Hand and wrist injuries are frequent. In 2009, about 3.5 million upper limb injuries were treated in the United States in emergency departments.3 This corresponds to an incidence of 1,130 upper extremity injuries per 100,000 persons per year. Another large survey in Denmark, including 13% of the population, estimated a much higher incidence of hand and wrist injury: 3,500 per 100,000 inhabitants per year.4 This rate is even higher among some heavy manual workers and craftsmen undertaking risky activities and among participants in risky sporting and leisure activities (e.g., boxers, snowboarders).5,6 In Maracaibo, for instance, miners have a rate of hand and wrist injury of 12,300 per 100,000 workers per year,7 an incidence of which the economic implications should not be underestimated. According to a recent estimate, approximately 216,000 adults suffer a distal radius fracture each year in the United States. This represents an incidence of 72 distal radial fractures per 100,000 inhabitants per year and a global annual cost of US $130 million.5,8 Certainly, hand and wrist injuries are not only frequent but also, if carelessly treated, an economic burden in terms of both cost of treatment and cost of reduced productivity. Carpal fractures are the second most common wrist injury, accounting for 6% to 15% of the total number of fractures below the elbow (▶ Fig. 1.1).9 The scaphoid is the most frequently fractured carpal bone, with an estimated annual rate of 8 fractures per 100,000 in females, and 38 fractures per 100,000 in males.10 Fracture dislocations of carpal bones are even more uncommon, representing about 2% of all fractures and/or dislocations of the hand. Fig. 1.1 Although the most frequent articular injury of the wrist involves distal radius, there are other fractures that may also induce adverse long-term sequelae unless properly treated. Of all carpal fractures, the one affecting the scaphoid is the most frequent, but fractures of the other carpal bones are not exceptional. An articular injury of the wrist may be open or closed. The injury may be isolated or may be associated with neurovascular and/or tendinous damage. Joint derangement may affect bones, ligaments, the capsule, and/or cartilages. If bones have fractures, these may be simple, multiple, or comminuted. The unstable fragments may displace, rotate, or remain undisplaced. The joints may dislocate or merely subluxate. Certainly, the variables are so diverse that it would be surprising to find a classification scheme that is both easy to remember and sufficiently comprehensive to include all possible conditions. Instead of elaborating imperfect classifications of injury, emphasis has been placed on providing tools to assess which factors determine the prognosis of each case. This facilitates the decision on what treatment will best meet the needs of each individual. The goal is not to find a single solution for all injuries that look alike; the goal is to find one strategy able to solve all the problems of every patient.

1.1 Incidence of Wrist Injury

1.2 Classification of Articular Injuries

1.3 Management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree