Intramedullary Fixation of Humeral Shaft Fractures

Saqib Rehman

Christopher Born

Phillip Langer

DEFINITION

Incidence: 3% to 5% of all fractures12

The AO/ASIF classification of humeral shaft fractures is based on increasing fracture comminution and is divided into three types according to the contact between the two main fragments:

Type A: simple (contact >90%)

Type B: wedge/butterfly fragment (some contact)

Type C: complex/comminuted (no contact)

Intramedullary nailing (IMN) can be used to stabilize fractures 2 cm distal to the surgical neck to 3 cm proximal to the olecranon fossa.12

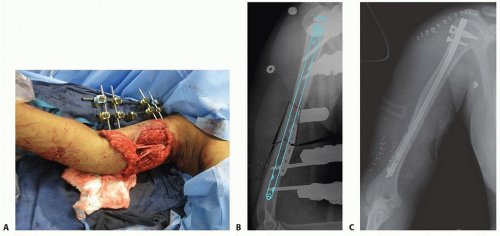

The precise role of IMN is not defined. Proponents offer the following benefits over formal open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF): It is minimally invasive, causing limited soft tissue damage and no periosteal stripping (preservation of vascular innervation)14; it is biomechanically superior; it is cosmetically advantageous (smaller incision); it is capable of indirect diaphyseal fracture reduction and metaphyseal fracture approximation. It can be helpful in severe open fractures in which plate and screw constructs could be less ideal from an infection standpoint (FIG 1).

Complications such as shoulder pain (with antegrade nailing), delayed union or nonunion, fracture about the implant, iatrogenic fracture comminution, and difficulty in the reconstruction of failures raise questions regarding the usefulness of IMN over ORIF.7

Biomechanically, intramedullary nails are closer to the normal mechanical axis; consequently, they can act as a load-sharing device if there is cortical contact.

Unlike plate-and-screw fixation, a load-bearing construct, intramedullary nails are subjected to lower bending forces, making fatigue failure and cortical osteopenia secondary to stress shielding less likely.

ANATOMY

Comparatively, there are several anatomic differences between the long bones of the upper extremity versus the long bones of the lower extremity (femur, tibia).

The medullary canal terminates at the metaphysis (vs. diaphysis).

Isthmus: junction is at the middle-distal third (vs. proximal-middle third).

Trumpet shape: The proximal two-thirds of the humeral canal is cylindrical; distally, the medullary canal rapidly tapers to a prismatic end at the diaphysis (hard cortical bone) versus the wide flare of the metaphysis (soft cancellous bone).

Because of the funnel shape of the humeral shaft, a true interference fit is difficult to obtain; therefore, proximal and distal static locking has become the standard of care for IMN of humeral fractures.

Neurovascular considerations include average distances of key structures from notable bony landmarks.

Axillary nerve to proximal humerus, 6.1 ± 0.7 cm (range 4.5 to 6.9 cm)

Axillary nerve to surgical neck, 1.7 ± 0.8 cm (range 0.7 to 4.0 cm)

Axillary nerve to greater tuberosity, 45.6 mm

Axillary nerve to distal edge acromion, 5 to 6 cm

Crossing of radial nerve at lateral intermuscular septum to proximal humerus, 17.0 ± 2.3 cm (range 13 to 22 cm)

Crossing of radial nerve at lateral intermuscular septum to olecranon fossa, 12.0 ± 2.3 cm (range 7.4 to 16.6 cm)

PATHOGENESIS

Biomodal distribution17

Young, male 21 to 30 years old: high-energy trauma

Older, female 60 to 80 years old: simple fall/rotational injury

Five percent open17

Sixty-three percent AO/ASIF type A fracture patterns17

Various loading modes and the characteristic fracture patterns they create

Tension: transverse

Compression: oblique

Torsion: spiral

Bending: butterfly

High energy: comminuted

Red flags

Minimal trauma indicates a pathologic process.

Disconnection between history and fracture type suggests domestic abuse.

NATURAL HISTORY

The humerus is well enveloped in muscle and soft tissue, hence its good prognosis for healing in most uncomplicated fractures.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with humeral shaft fractures present with arm pain, deformity, and swelling.

Demographics, medical history, and information regarding the circumstance and mechanism of injury should be obtained.

Particularly significant in upper extremity trauma: Hand dominance, occupation, age, and pertinent comorbidities must be solicited from the patient. All of these factors play a major role in determining whether to pursue surgical versus nonsurgical treatment.

On physical examination, the arm is typically shortened, angulated, or grossly deformed, with motion and crepitus on manipulation.

Document the status of the skin (open vs. closed fracture) and perform a careful neurovascular evaluation of the limb.

If indicated, Doppler pulse and compartment pressures should be checked.

Always examine the shoulder and elbow joint for possible associated musculoskeletal pathology.

Examine the radial nerve for evidence of injury by testing resistance to wrist and finger extension, with care to distinguish intrinsic extension from extrinsic extension.6

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

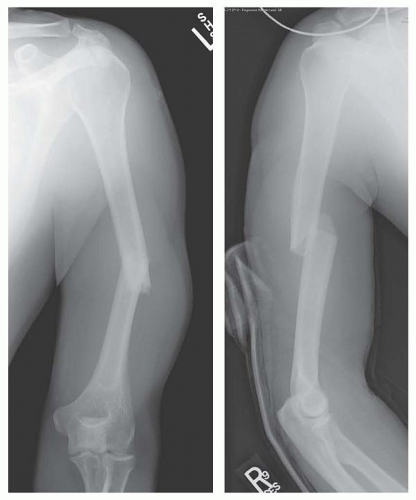

Initial studies must always include orthogonal views (anteroposterior [AP] and lateral radiographs) of the fracture site, shoulder, and elbow (FIG 2). To obtain these radiographs, move the patient rather than rotating the injured limb through the fracture site. Lateral imaging typically needs to be done with a transthoracic projection in order to prevent rotation through the fracture site with positioning.

Traction radiographs may be helpful with comminuted or severely displaced fractures, and comparison radiographs of the contralateral side may be helpful for determining preoperative length.

Computed tomography (CT) scans rarely are indicated. Rare situations in which they should be obtained include significant rotational abnormality, precluding accurate orthogonal radiographs, and suspicion of possible intra-articular extension or an additional fracture or fractures at a different level.

Doppler pulse and compartment pressures should be checked, if indicated, following a thorough physical examination.

Suspicion of vascular injuries warrants an angiogram.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Osteoporosis

Pathologic fractures

High- or low-energy trauma

Open or closed fractures

Domestic abuse

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Most non- or minimally displaced humeral shaft fractures can be successfully treated nonoperatively, with union rates of more than 90% often reported.12

Common closed techniques include hanging arm cast, coaptation splint, Velpeau dressing, abduction humeral/shoulder spica cast, functional brace, and traction.

Each of these modalities has been successfully employed, but most commonly, either a hanging arm cast or coaptation splint is used for 1 to 2 weeks followed by a functional brace, tightened as the swelling decreases.

Hanging arm casts are a very good option for displaced, midshaft humeral fractures with shortening, especially oblique or spiral fracture patterns, if the cast is able to extend 2 cm or more proximal to the fracture site.

For nonoperative treatment to be effective, the patient should remain upright, either standing or sitting, and avoid leaning on the elbow for support. This allows for gravitational force to assist in fracture reduction.

As soon as possible, the patient should begin range-ofmotion (ROM) exercises of the fingers, wrist, elbow, and shoulder to minimize dependent swelling and joint stiffness.

Acceptable alignment of humeral shaft fractures is considered to be 3 cm of shortening, 30 degrees of varus/valgus angulation, and 20 degrees of anterior/posterior angulation.10

Varus/valgus angulation is tolerated better proximally, and more angulation may be tolerated better in patients with obesity.

Patients with large pendulous breasts are at increased risk for varus angulation if treated nonsurgically.

No set values for acceptable malrotation exist, but compensatory shoulder motion allows for considerable tolerance of rotational deformity.10

Low-velocity gunshot wounds act as closed injuries after initial treatment. Following irrigation and débridement of skin at entry and exit sites, tetanus status confirmation, and prophylactic antibiotic initiation, nonoperative treatment modalities are commonly employed.10

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Successful nonoperative management may be impossible for various reasons.

Fracture pattern (eg, displaced, comminuted, segmental [segmental fractures are at risk of nonunion of one or both fracture sites])

Prolonged recumbency

Morbid obesity

Large, pendulous breasts (in women)

Patient’s inability to maintain a semisitting or reclined position owing to polytraumatic injuries or patient noncompliance

Operative indications include the following:

Proximal humeral fractures with diaphyseal extension

Massive bone loss

Displaced transverse diaphyseal fractures

Segmental fractures

Floating elbow

Pathologic or impending pathologic fractures

Open fractures

Associated vascular injury

Intra-articular extension

Polytrauma

Spinal cord or brachial plexus injuries

Poor soft tissue over the fracture site(s), such as thermal burns

The most commonly cited overall best indication for IMN from this extensive list is a pathologic or impending pathologic fracture.

The need for operative intervention secondary to radial nerve dysfunction after closed manipulation is controversial.

There are advocates for both early nerve exploration and observation.

This condition was once thought to be an automatic indication for surgery; however, this assumption has since been called into question.12

Isolated comminution is not an indication for operative treatment.12 However, if surgical fixation is chosen over nonoperative management, antegrade IMN has been proposed by some to be favored over plate fixation for comminuted or segmental fractures.2

Relative contraindications include the following:

Open epiphyses

Narrow intramedullary canal (ie, <9 mm)

Prefracture deformity of the humeral shaft

Open fractures with obvious radial nerve palsy and neurologic loss after penetrating stab injuries

The last two conditions require nerve exploration with subsequent plate-and-screw fixation.

Chronically displaced fractures should be treated with ORIF rather than IMN to prevent traction-induced brachial plexus palsy and radial nerve injury.

Preoperative Planning

When selecting implant size, consider canal diameter, fracture pattern, patient anatomy, and postoperative protocol.

Nail length and diameter should take into account the distal narrowing of the humerus.

Estimations of the nail diameter, length, and necessity of reaming can be made using preoperative roentgenograms of the uninjured humerus.

Alternatively, the length and diameter of the medullary canal can be ascertained intraoperatively using a radiopaque gauge and C-arm imaging of the intact humerus. Use of a radiolucent table top will substantially improve the quality of the image as well as the ability to obtain accurate C-arm images.

Position the gauge anterior to the unaffected humerus with its distal end 2.5 cm or more proximal to the superior edge of the olecranon fossa and 1 cm distal to the superior edge of the articular surface.

Move the C-arm to the proximal end of the humerus and read the correct length directly from the stamped measurements on the nail length gauge. The IMN should end approximately 1 to 2 cm proximal to the olecranon fossa.

Measure the length of the IMN to allow the proximal end to be buried. This will reduce the incidence of subacromial impingement if an antegrade technique is used or encroachment

on the olecranon fossa and blocked elbow extension if a retrograde approach is chosen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree