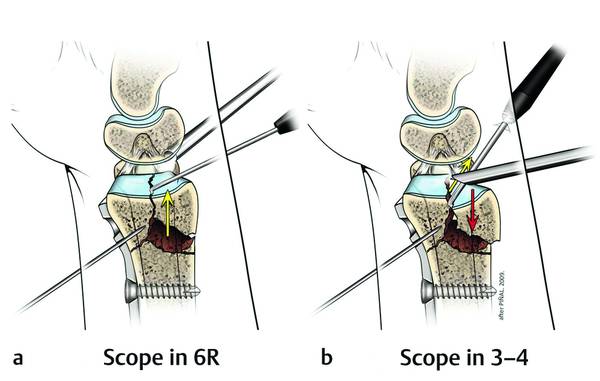

Intra-articular Fractures of the Distal Radius (AO type C3), (Dry) Arthroscopic Approach Contrary to general belief, arthroscopically assisted reduction in distal radius fractures is being performed in an expeditious manner and with minimal OR resource consumption by experienced groups. Arthroscopy allows one to see with good illumination and magnification, and with minimal morbidity, even the most hidden corners of the radius articular surface. It is also well known that fluoroscopy is not very sensitive in detecting small (2-mm) step-offs, which have been demonstrated to have an impact on the clinical result.1–3 Furthermore, several authors have shown better results in prospective randomized studies when arthroscopy is used.4–6 Despite all of this evidence, there is general reluctance in the hand surgery community to accept the usefulness of the arthroscope.7 In my own view, the poor reputation of the use of the arthroscope prevails mainly for three reasons. Perhaps the most prominent lies in the technical difficulties and cumbersome nature of combining the classic (wet) arthroscopic part and the open reduction and internal fixation part itself. On the one hand, massive tissue infiltration makes the latter extremely awkward; on the other, water running out through the incisions and portals obliges one to combine the less effective Kirschner-wire and external fixation methods to the detriment of the more stable volar locking plate when arthroscopy is used. Another major reason for the dismissal of the arthroscope is the fact that the arthroscope is reserved for the most complex comminuted articular fractures. The paradox is that while it is true that C3 fractures are the ones that benefit most from arthroscopic fine-tuning, these are the ones that prove more difficult to deal with, and where the surgeon needs the highest skills. If the surgeon (and the team) does not develop a routine of using the arthroscope in the easy fractures, they will not be prepared to manage the complex ones. The frustrated surgeon will put aside the most useful surgical instrument that technology has put into our hands for restoring the anatomy after distal radius fractures. Finally, it should be emphasized that the most common error when starting is to introduce the arthroscope at the end of the operation once all the rigid fixation has been done in order to “confirm the anatomical reduction.” At this stage, correcting any misplaced fragment and achieving stable fixation is almost impossible, leaving the surgeon with the difficult decision of accepting an inaccurate reduction or having to transform the ideal “rigid” fixation into a “voodoo” exercise, with K-wires maintaining a tenuous fixation. This conundrum emphasizes how important logistics are, the more so the more complex the fracture. It is imperative to follow the correct sequence in order to be able to modify the fixation should the need arise. It cannot be denied either that the use of the arthroscope in intra-articular distal radius fractures adds a level of complexity to an already complex operation. But it provides indisputable advantages as well: the ability to remove debris and hematoma, to see inside the joint with light and magnification, to directly manipulate intra-articular fragments, and to evaluate for concomitant ligamentous injury. Our role as surgeons is to master any technique that may have a benefit for a patient’s well-being. The purpose of this chapter is to present technical tips to make the arthroscope a friendly and useful instrument when dealing with distal radius fractures. To avoid some of the inconveniences, the arthroscopy has to be carried out “dry.” It is paramount to understand that the arthroscope is a tool to fine-tune the reduction achieved by classic methods. Slickness and proficiency in the management of distal radius fractures are essential. Logistics are fundamental in this “complex” operation. The management of C3 fractures is difficult and is not recommended until the surgeon and OR personnel have enough experience with the management of simple fractures. A preoperative CT scan is invaluable until one is acquainted with the procedure: the anatomy may be so distorted that it may take too long before the surgeon can find his or her way inside the joint. Finally, the assistance of another surgeon is invaluable until one is familiar with the logistics of the operation, and is indispensable in more complex fractures. Before addressing the treatment of the fracture itself, the surgeon needs to be acquainted with the dry arthroscopic technique.8,9 The technique can be summarized in the three basic rules: The valve of the sheath of the arthroscope is kept open at all times to allow air circulation. Suction of the shaver or bur is used only when aspiration is necessary, and left in the “off” position for the remainder of the operation. Otherwise, the contents of the joint will be agitated by the suction, obscuring vision through the scope. The joint is flushed with 5- to 10-mL aliquots of saline to clear debris and blood as needed. The operation is scheduled as soon as possible in our practice, unlike many authors who recommend to wait for 3 to 5 days to minimize bleeding of the fracture site and to avoid major extravasation of fluid risking a compartment syndrome. The latter problem does not arise if the surgeon uses the dry arthroscopic technique. We have found few contraindications apart from an overt infection. The dry technique is contraindicated when using thermal probes unless intermittent fluid irrigation is used. Typically, the operation can be summarized in the following sequence:10,11 Temporary fixation of the articular fragments with K-wires to a volar locking plate under fluoroscopic control Arthroscopic fine-tuning of the reduction Rigid articular fragment fixation under arthroscopic guidance Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) and midcarpal exploration A flexor carpi radialis (FCR) approach is used to address the typical four-part fracture. A 6-cm incision is made overlying the FCR. The tendon sheath is divided and the FCR is retracted ulnarly. The pronator quadratus is elevated from the fracture. The brachioradialis tendon is never released from the radial styloid, as in the acute setting it is not a deforming force. A volar locking plate is provisionally applied and stabilized to the shaft of the radius by inserting a screw into the elliptical hole on the stem of the plate. This will allow some adjustment of the plate as needed. Next, the reduction of the distal fragments is undertaken by traction and flexion. The dorsal fragments are manually compressed to the construct as the plate acts as a mold. Usually, several attempts and maneuvers are needed before the “best” provisional reduction is obtained, as judged by the fluoroscopic views and direct observation of the metaphyseal component of the fracture. Radial length, volar tilt, and radial inclination should be corrected and held with the aid of the plate. The articular fragments are then provisionally secured to the distal plate by inserting Kirschner wires (K-wires) through the auxiliary holes and an additional proximal screw is inserted. It is paramount not to use locking pegs/screws at this stage, as fixation may need to be modified by the arthroscopic findings. At this point, we suspend the hand from a custom-made traction system with 7 to 10 kg of distraction.12 A 2.7-mm/30° scope is used for most cases. Because of edema and the disrupted bony anatomy, it is slightly more difficult to establish the portals than in a standard arthroscopy case. However, with deep palpation, the Lister tubercle can be located as well as the joint space just distal to it. This guides the placement of the 3–4 portal. Small transverse incisions are used for each portal as they heal with minimal scarring and do not require suturing at the end of the operation. The entrance of the portal is enlarged with a mosquito clamp, and the scope is introduced and directed ulnarly to establish another portal for triangulation. Use of the 4–5 portal is avoided to prevent interference with the reduction of the dorsoulnar radius. Instead, the 6R portal is the preferred ulnar portal for triangulation. This portal is established by palpating the proximal rounded surface of the triquetrum; the portal placement is just proximal to the triquetrum but as distal as possible. This avoids the TFCC, which may be detached from the dorsal capsule or fovea and may impede the entrance into the radiocarpal joint. With the scope in the 3–4 portal, a 2.9-mm shaver is inserted into the 6R portal to aspirate blood and debris. The joint is irrigated with saline in 5- to 10-mL aliquots from a syringe attached to the valve of the scope. After the fragments that need to be mobilized are identified from the 3–4 view, the scope is swapped to 6R. The scope remains in 6R until the completion of the fixation. In this position, the scope rests on the ulnar head and the TFCC, this being the only stable point in a typical distal radius fracture. If the scope is kept in the 3–4 (or 4–5) portal, it rests on the unstable dorsal distal radius; this can displace reduced fragments or impede their reduction (▶ Fig. 21.1). Although the volar-radial portal is useful for addressing dorsal rim fragments10,11 we prefer to keep the scope in 6R, advance the scope volarly, and turn the lens dorsally to view the dorsal rim. This avoids changing portals and re-displacing volar fragments that are not yet rigidly fixed. Fig. 21.1 (a) When the scope is placed in 6R, it rests on the stable platform of the ulnar head. (b) If the scope is placed in any other portal, it conflicts with the reduction (red and yellow arrows) and is unstable. (Copyright © 2011 by Dr. F. del Piñal.) Except in the most complex cases, only one or two fragments will need to be addressed arthroscopically, and usually these fragments are depressed. Several authors recommend elevating these fragments by inserting an instrument into the metaphysis (proximal to the fragment) through an additional dorsal skin incision. Our preferred technique is to use a shoulder or knee probe in the 3–4 portal and hook the fragment to pull it distally (▶ Fig. 21.2, ▶ Fig. 21.3

21.1 Introduction

21.2 Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree