Chapter 2 Injury prevention

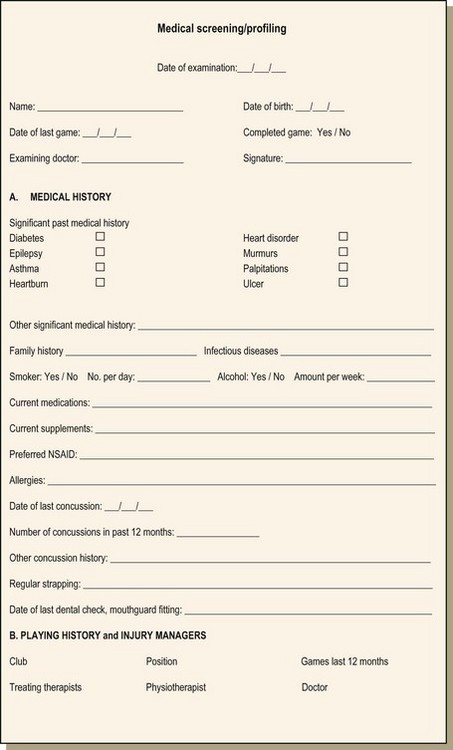

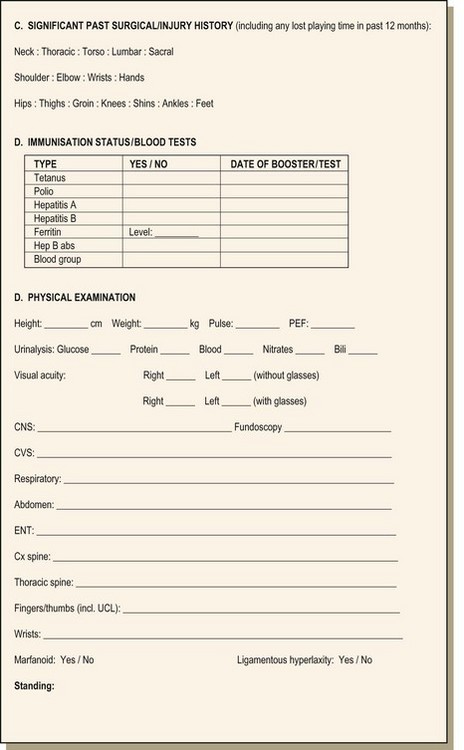

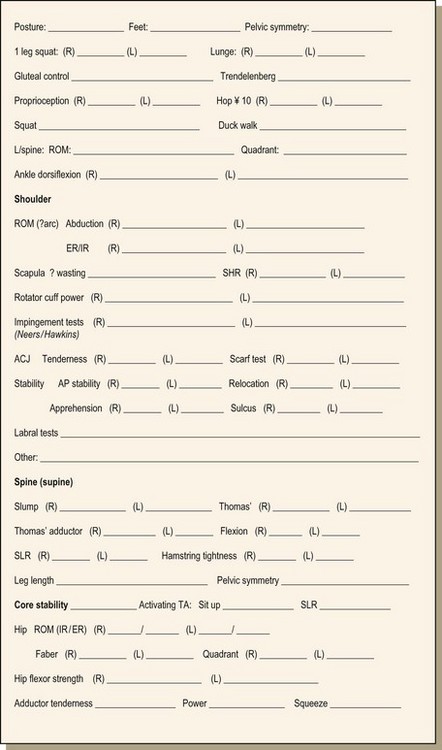

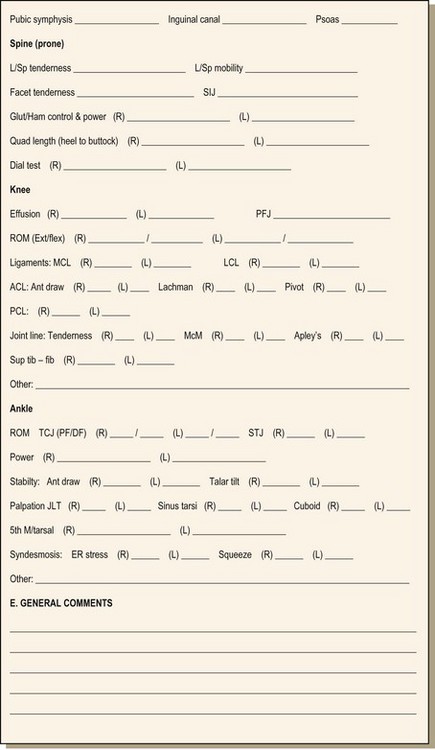

The ability to prevent an injury is the ‘holy grail’ of all sports therapists. To reduce the occurrence of an injury and thereby keep the athlete training and competing is the ultimate in excellent care. There are many factors that contribute to achieving this goal and there are many factors that we have no control over that may jeopardise our best efforts; however, one way of identifying which athlete is at risk of what injury, is to perform a screening or profiling medical. This is a top-to-toe musculoskeletal survey of the athlete, taking into consideration their sport, playing position, demands of the sport, their morphology, strength, stature, muscle balance, proprioception, posture, biomechanics, joint range of movement and stability, body control, flexibility and coordination. This is a long list but the process involves progressing through the body, examining each joint and muscle group with the insight of the athlete’s past injury history, identifying as you go along any deficiencies, imbalances, structural abnormalities or injuries that would put the athlete at risk of injury. A suggested medical examination protocol is shown in Figure 2.1.

CORE STABILITY

Low-load stability muscles

Low-load stability muscles

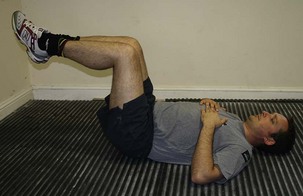

The traditional transversus abdominis exercise is in crook lying and gentle flattening of the low abdomen towards the spine, while breathing. A facilitation technique for those athletes who are struggling with the concept is to use the muscles that stop them from urinating and this can help activate the transversus muscle (Fig. 2.2).

Floor exercises

Floor exercises

3. Unilateral hip and knee extension

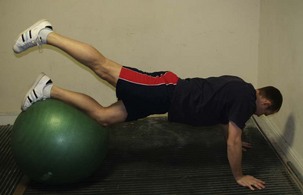

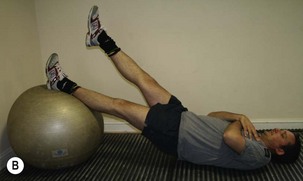

Gym ball exercises

Gym ball exercises

Higher-level exercise

2. Traditional sit-ups and their many variations will train the high-level muscles in small movement but will also help strengthen them for their control role as well.

Gluteal muscle (glutes) exercises

3. Hip extension/abductions in sidelying

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree