Fig. 3.1

a Nail bed anatomy shown in sagittal section. b Surface anatomy of the perionychium consists of the paronychium, hyponychium, eponychium, and nail bed. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

The radial and ulnar digital nerves trifurcate at the level of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint with the dorsal branches supplying sensation to the nail. [5] The blood supply to the nail apparatus is provided by terminal branches of the volar digital arteries and the capillary loops they form. [6] Venous drainage is concentrated toward the proximal nail bed and nail fold and then continues along the dorsum of the finger . [7, 8] The lymphatics drain parallel to the venous system. The hyponychium is extremely dense with lymphatics to protect from frequent exposures. [9, 10]

Epidemology

The nail apparatus is the most commonly injured structure in the hand. Injuries occur most often in older children or young adults. The long finger is the most frequently injured digit and distal injuries to the nail apparatus are the most common. Doors are the most encountered method of traumatic injuries to the nail apparatus. [11] Injuries can be subdivided into subungual hematoma , simple laceration, stellate laceration, crush injury or nail avulsion. [12, 13] Crush injuries are the most frequent. There is a 50 % chance of bone involvement with nail bed injuries so X-ray examination is always recommended.

Injuries

Subungual Hematoma

Compression injuries to the nail often result in nail bed lacerations with bleeding beneath the nail leading to a subungual hematoma (Fig. 3.2) . This fluid collection beneath the nail can lead to severe throbbing pain which is an indication for hematoma drainage. The decision to drain the hematoma versus nail plate removal with exploration has evolved over time. Currently, the recommendation is to remove the nail plate with exploration and repair of the nail bed laceration if the nail edges are disrupted. If the nail edges are intact then hematoma drainage without nail plate removal and exploration is preferred. The percentage of hematoma is no longer an indication for exploration. This is supported by a prospective 2-year study of 48 patients with subungual hematomas that demonstrated no complications of nail deformity with conservative treatment of drainage only, regardless of the hematoma size. [14] More recently, a systematic review of the literature by Dean et al. showed there was no difference in aesthetic outcome when comparing nail bed repair and simple decompression (drainage) [15].

Fig. 3.2

Subungual hematoma. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

Subungual hematoma drainage should begin with surgical preparation of the finger or entire hand . This decreases the chance of bacterial inoculation during drainage. We prefer povidone–iodine (betadine) scrub followed by trephination over the hematoma with a battery powered microcautery unit (Fig. 3.3). Once the heated tip is passed through the nail it is cooled by the hematoma which decreases iatrogenic injury to the nail bed. The trephination hole must be large enough to allow continued drainage of the hematoma .

Fig. 3.3

The author’s preferred method of subungual hematoma drainage with a battery operated electrocautery unit. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

Nail Bed Injury and Repair

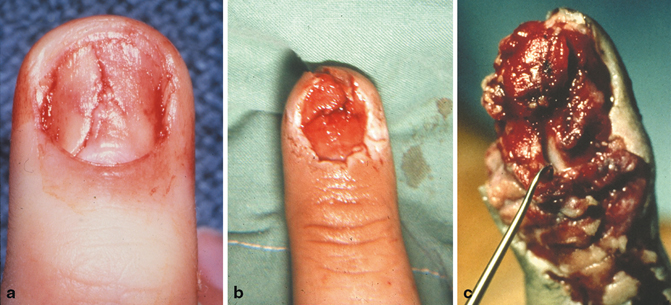

Nail bed lacerations can occur from a sharp injury or crush . The resultant injuries can be subcategorized into simple lacerations, stellate lacerations, or severe crush (Fig. 3.4). Stellate lacerations and crush injuries often involve fragmentation of the nail plate. Great care is taken during nail plate removal to prevent iatrogenic injury to the nail bed. Repair of stellate lacerations can have good outcomes with meticulous approximation of the nail bed segments. The prognosis for crush injuries is poorer because of the nail bed contusion in addition to laceration. A study by Gellman demonstrated that simple nail plate trephination of crush injuries in children produced equal to, or superior results, when compared to nail removal and formal nail bed reconstruction. [16]

Fig. 3.4

Nail bed laceration classification. a Simple nail bed laceration. b Stellate nail bed laceration. c Crush injury. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

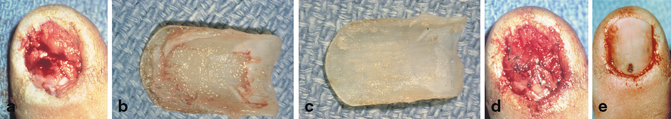

Nail bed repair is performed under sterile technique and repair can be successfully performed up to 7 days after injury although early repair is recommended (Fig. 3.5). A digital block is performed with 1 % lidocaine with epinephrine and the finger or entire hand is prepped and draped. The digit is exsanguinated and a tourniquet is placed around the proximal phalanx region of the finger . The nail plate is removed atraumatically with iris scissors or a Kutz elevator. Care is taken to avoid inadvertent injury to the nail bed during nail plate removal with iris scissors. The tips of the scissors should be pointed toward the nail plate and careful spreading in the plane of the nail should be performed distal to proximal. Once removed, the undersurface of the nail is cleaned of any fibrinous debris and the nail plate is soaked in povidone–iodine solution for reapplication if the nail plate is salvageable. Loupe magnification is utilized to inspect the nail bed surface. Conservative debridement is performed along with copious wound irrigation. Repair is performed with simple sutures of 7–0 chromic on a spatulated needle. An alternate method, is the utilization of 2-octylcyanoacrylate (dermabond) for repair. Strauss et al. described this technique and cited equivalent aesthetic and functional results when compared to suture repair . [17]

Fig. 3.5

Nail bed repair. a Nail bed stellate laceration. b Removal of the nail plate. c Debridement of the nail plate undersurface. d Nail bed following repair with 7–0 chromic sutures. e Replacement of the nail plate with drainage hole. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

Postoperatively the nail bed repair must be protected. If the native nail plate is intact, it can be replaced and held either proximally with a horizontal mattress suture through the nail fold or distally with an interrupted suture through the hyponychium . If the eponychial fold is badly damaged, Bristol and Verchere described a figure of eight suture to secure the nail plate that is placed laterally through the paronychial folds [18]. If the nail plate is too badly injured we recommend the use of silicone sheeting or, as a secondary option, non-adherent gauze or suture packet material. Every effort should be made to preserve the native nail, because the use of silicone sheeting is associated with an increased rate of nail deformities, with split nail being the most common. [19] Replacement of the nail, or protection with a secondary material, allows the nail bed repair to be anatomically molded and can splint any associated distal phalanx fracture. [20] Non-adherent dressings are then applied and an aluminum splint is placed. The patient is seen 5–7 days after the repair and dressings are removed at that time. Continued splinting may be required for pain management and distal phalanx fracture management for an additional 2–3 weeks .

Nail Bed Avulsion

A nail bed avulsion injury presents with the nail bed attached to the undersurface of the nail plate (Fig. 3.6). Often the nail bed laceration is located beneath the eponychial fold and the nail plate remains attached to the distal aspect of the nail bed. A common avulsion injury seen in children is associated with Salter–Harris type I fracture. The distal aspect of the fracture remains attached to the nail plate and the nail plate is displaced above the proximal nail fold. Radiographic evaluation is essential in this type of injury. Adequate reduction of the fracture is accomplished with replacement of the nail plate beneath the nail fold and repair of the nail bed.

Fig. 3.6

Nail bed avulsion injury. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

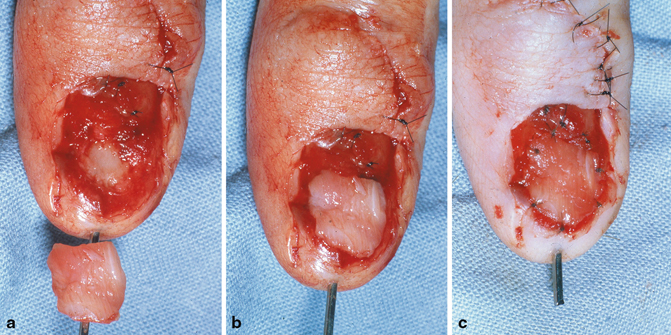

The avulsion nail bed injury is managed with removal of the avulsed nail bed from the undersurface of the nail plate and replacement of the nail bed as a free graft. The nail bed survives in a similar fashion to skin grafts by serum imbibition, inosculation, and revascularization. Suture of the free nail bed graft often requires mobilization of the nail fold due to the proximal location of the injury. Two incisions can be placed laterally and perpendicular to the nail fold. This allows elevation of the eponychial fold and visualization of the proximal extent of the injury (Fig. 3.7). After repair of the nail bed avulsion, the nail fold incisions are approximated. If multiple small pieces of nail bed are avulsed they are all placed as free grafts. The nail bed can be placed directly onto distal phalanx cortex and survive. Rarely, a situation arises where there are multiple small nail bed pieces and removal from the fragmented nail plate could result in further injury. In this case, the nail plate is replaced without an attempt to separate the fragments from the undersurface of the nail plate.

Fig. 3.7

Elevation of the eponychial fold. a Incisions are placed at 90°angles to the eponychial fold for proximal nail bed exposure. b Elevation of the eponychial fold exposes the proximal germinal matrix. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

Nail Bed Defect

Assessment of nail bed defects begins with the recognition of involvement of the sterile matrix or germinal matrix and identification of the depth of injury. Partial-thickness injuries to the sterile or germinal matrix will heal without intervention. Non-repaired full-thickness injuries often result in scarring and nail deformity. For central full-thickness defects, Johnson [21] described releasing incisions at the lateral paronychial fold with nail bed advancement. This technique works for a defect that is less than one third the nail bed width, usually 3–5 mm in size, and good condition of the remaining nail bed [22].

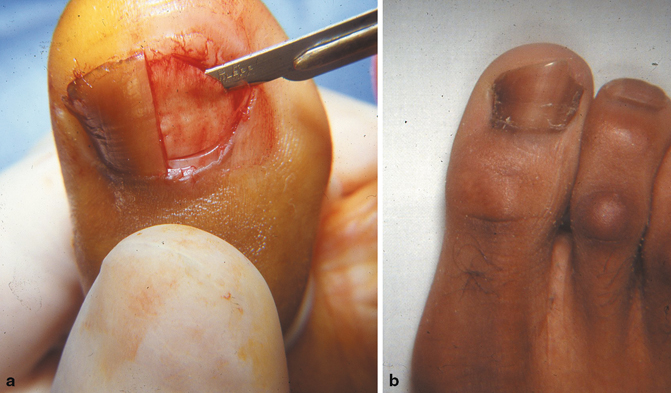

Full-thickness nail bed defects of the sterile matrix can be reconstructed with split-thickness nail bed grafts (Fig. 3.8) [23, 24]. Split-thickness grafts can be obtained from the remaining uninjured nail bed if the defect is less than 50 % in size. For defects greater than 50 %, a graft must be obtained from an adjacent finger or toe (Fig. 3.9). Harvesting the graft from the toe is more favorable because of the lower risk of nail deformity resulting from grafts harvested too deeply.

Fig. 3.8

Nail bed grafting. a Nail bed with full-thickness defect of the sterile matrix and split-thickness graft. b Placement of graft. c Graft sutured to defect. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

Fig. 3.9

Graft harvest. a Harvest of split-thickness sterile matrix graft from toe. b Postoperative donor site. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

Nail bed defects of the germinal matrix require full-thickness germinal matrix grafts, because the deep cells of the germinal matrix are necessary for a new nail to grow. The biggest disadvantage of a full-thickness germinal matrix graft is the loss of nail growth at the donor site.

To harvest a nail bed graft the finger or toe to be used as a donor is anesthetized with a digital block of 1 % lidocaine with epinephrine. After prepping and draping the finger or toe, a tourniquet is placed at the base of the proximal phalanx. The nail plate is removed atraumatically with scissors or a Kutz elevator and preserved for reapplication at the end of the procedure. For split-thickness grafts, it is helpful to outline the donor graft size with a surgical marker. A No. 15 blade scalpel is then used to tangentially raise the split-thickness graft. The blade should be visualized through the graft during the harvest to prevent full-thickness injuries. It is better to harvest a graft that is too thin than to create a full-thickness nail bed injury . For larger graft harvests small forceps can be used to provide counter traction because the curve of the nail bed makes harvest with the scalpel alone difficult. The graft is then sutured to the defect with 7–0 chromic suture, and the nail plate replaced for bolstering of the graft.

Distal Phalanx Fracture

Fifty percent of nail bed injuries have an associated distal phalanx fracture . [13] Radiographic evaluation is a key component of fingertip injury evaluation. Distal tuft fractures and non-displaced distal phalanx fractures can be treated with nail bed repair and replacement of the nail plate which will act as a splint for the fracture. If the nail plate is missing or badly damaged additional pin fixation may be needed for fracture stability. Displaced fractures and fractures proximal to the nail fold are best treated with operative fixation utilizing 0.028-inch Kirschner wires (Fig. 3.10). Two longitudinally oriented or crossed K-wires should be placed to prevent rotation, the wires should not pass through the DIP joint, if possible, to avoid long-term DIP joint stiffness. Pins are removed at 3–4 weeks in the office.

Fig. 3.10

Distal phalanx fracture fixation. a Comminuted and displaced distal phalanx fracture. b Reduction and percutaneous pinning. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

Comminuted fractures often have small pieces of bone which are adherent to the nail bed. Repair of the nail bed injury allows approximation of the bony fragments. Replacement of the nail or, if unavailable, placement of a piece of silicone acts as a splint for fracture healing. The goal is bony union with an anatomic dorsal cortex for the nail bed to rest on. Although comminuted tuft fractures often result in fibrous nonunion, they are mostly asymptomatic .

Seymour fracture is a unique injury that occurs in children. This is a Salter–Harris type I fracture through the physis if the distal phalanx base, which often is associated with an avulsion nail bed injury. Reduction of the distal segment beneath the proximal nail fold often results in anatomic reduction. Splinting is usually satisfactory but there are some circumstances in which supplemental fixation is required for unstable fractures. Kirchner wires can be used for fracture stability but the DIP joint should be left free if possible (Fig. 3.11). [25].

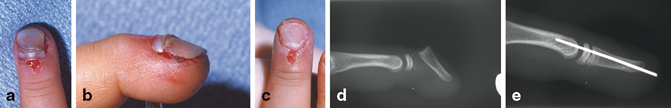

Fig. 3.11

Seymour fracture repair. a and b Seymour fracture with avulsion nail bed injury. c Following reduction of the fracture and replacement of the nail beneath the nail fold. d Radiographic imaging of a Seymour fracture. e Following reduction and percutaneous pinning. Published with kind permission of © Nicole Z. Sommer, MD [2014]. All rights reserved

Amputation

Injuries to the nail apparatus occur with distal amputations. Management depends on the level of injury and the integrity of the remaining structures. Reconstructive management entails a variety of procedures including revision amputation, skin and nail bed graft placement, local flap reconstruction and replantation . The reconstructive methods that affect the nail apparatus will be discussed in this section .

If the injury involves exposure of the distal phalanx, there are several methods of management for bony coverage. Revision amputation with bone shortening and suturing the remaining skin over the distal phalanx is one option. Local flap advancement is another option [26]. With either of these choices it is essential that the suturing of the skin to the nail bed edge is done in a tension-free manner. If there is any tension at this junction the nail bed will grow in a volar direction and the nail plate will follow creating a hook nail deformity. Similarly, if the nail bed is left longer than the distal phalanx, the nail bed will collapse volarly and a hook nail will develop. The distal phalanx length is crucial in supporting the overlying nail bed. Therefore, when shortening an amputation, the nail bed should be cut to the same length as the distal phalanx.

Volar VY advancement flaps are often used to replace lost hyponychium in a distal amputation injury. [27] Distal nail bed injuries can be reconstructed with the addition of a nail bed split-thickness or full-thickness graft to the distal de-epithelialized portion of the VY flap [28]. The entire nail bed can be reconstructed with this method. Another option is the reverse homodigital artery flap that has been recently described for coverage of a partially amputated distal phalanx with exposed bone. [29] This technique can be used with or without the addition of a nail bed graft.

Replantation of the fingertip can be attempted if the injury is at or proximal to the eponychial fold. Revision amputation is usually preferred for amputation distal to the level of the nail fold. Management of the nail depends on the percent of nail remaining. If greater than 25 % of the nail is still present distal to the nail fold, the nail should be preserved. If less than 25 % of the nail remains then a nail bed ablation should be performed. Ablation requires removal of the dorsal roof and the ventral floor of the nail fold. The eponychial fold skin is preserved and used for additional soft tissue coverage.

Amputation in children can present with fingertip avulsions with the nail bed present on the avulsed digit. In this unique circumstance, the fingertip and nail bed are sutured back into place with minimal or no debridement. Often the avulsed segment will survive from serum imbibition and inosculation in a similar manner to a skin graft. Composite graft take is most successful in children younger than 3 years old. In older children, tip amputations can be defatted and replaced as a “cap” graft [30] for better success than composite grafting.

Postoperative Management

Patients with nail apparatus injuries are often seen in follow up 5–7 days from the injury. At this visit the bandages are soaked off and the repair is inspected. Any sutures securing the nail plate are removed to prevent a sinus tract from forming. Often chromic sutures are used for re-approximation of skin but occasionally nylon sutures are present and can be removed at 10–14 days from the operation.

If the nail was reapplied, the patient should be informed that the nail will slowly be pushed off by the advancing nail in approximately 1–3 months. Silicone or suture material falls off earlier. The nail grows at a rate of 0.1 mm/day and the patient can expect a delay of 3–4 weeks prior to nail growth resumption. [31] Two to three millimeters of total nail growth occurs per month and the nail has a bulge at its leading edge during growth (Fig. 3.12). It takes 6–9 months for a new nail to completely grow. Toenails grow more slowly than fingernails with their linear growth being 30–50 % that of finger nails. [32, 33]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree