42

Initial management of the polytraumatised patient

Introduction

Patients involved in serious accidents are becoming rarer and rarer in developed countries, but are more likely than ever to arrive at hospital alive however severe their injuries. This is a result of better communications and improved pre-hospital care. Serious accidents often involve young people with great potential for healing and a long productive life ahead of them. The stakes are high and the first few hours have a profound effect on the long-term outcome. Working to a system allows a team to work quickly and efficiently. This chapter presents a simple system for this initial management.

History

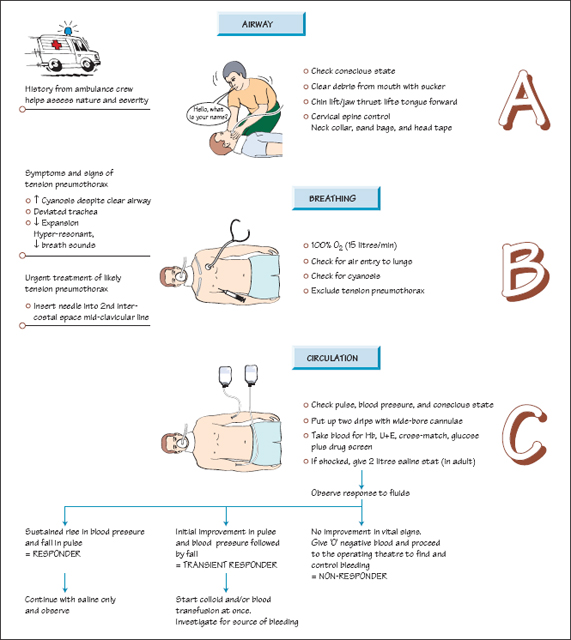

The patient may not be able to give a history, but a description from the paramedics of the energy involved in the accident will give a clue to the likely type and severity of the patient’s injuries.

As a general rule if there is one significant injury then there are likely to be more, so always do a complete survey in a seriously injured patient.

Initial management

The initial approach to a seriously injured patient is given by the acronym ABC followed by D and E.

Airway and neck stabilisation (A)

- Start by asking the patient for their name. If they can answer then you have confirmed that their airway (A), breathing (B) and conscious state are all reasonable.

- While this is being done someone should be taking control of the neck with ‘in-line immobilisation’ , prior to the neck being stabilised with a stiff collar, sandbags and tape, just in case there is an unstable fracture of the cervical spine.

- If the patient does not answer, start by checking the mouth and throat for obstructions, broken teeth and other material. A sucker is safer than a finger, as a semiconscious patient may bite.

- A chin lift or jaw thrust will lift the tongue forward from out of the throat if this is the cause of the obstruction.

Breathing (B)

Start giving 100% oxygen at 15 l/min (full bore). Check for breathing and air entry into the lungs by looking for chest movement and listening to the lungs. If the patient does not appear to be breathing start bagging them with an Amb-bag and prepare for intubation. If the patient’s colour is not good, check again that the airway is clear, then check for a tension pneumothorax. The most obvious sign will be a deviated trachea.

If a tension pneumothorax is suspected then a blue needle needs to be introduced into the second intercostal space in the mid-clavicular line. If the diagnosis is correct the patient’s condition should improve at once, and a chest drain can then be inserted later. If not, little has been lost.

Circulation (C)

Two wide-bore cannulae should be introduced, one into each antecubital vein (front of the elbow). Bloods are drawn for cross-match, full blood count, electrolytes, glucose and drug screen. Two litres of Hartmann’s solution can then be given as quickly as they can be transfused (stat) if the patient is in deep shock. This fluid challenge will give a clue to the seriousness of the situation and allow you to plan the next stage. If the patient’s blood pressure rises and their pulse falls back to normal levels and then they remain stable, the patient is a ‘responder’. No further aggressive action needs to be taken for the moment, although blood should still be cross-matched.

If the patient improves but then starts to deteriorate again, then a plasma expander is needed urgently and further investigations are necessary to find the source of the bleeding. ‘O’ -negative or type-specific blood may be ordered to save time on the cross-match. Up to 8 units should be ordered in the first instance.

If there is no response to the fluid challenge then the patient needs ‘O’ -negative blood at once and surgery to try to stem the haemorrhage at once. The main sites for heavy bleeding are the chest, abdomen and pelvis.

Disability (D)

Check and record the patient’s conscious state using the Glasgow coma scale (see Chapter 47). At every stage keep rechecking the ABC, especially if the patient’s condition starts to deteriorate.

Exposure (E)

Remove all clothes and check the patient from top to toe using the ‘look, feel, move’ system (see Chapters 3 and 21). Log-roll the patient to check the back as well, looking all over the body for cuts, bruises and deformity. A rectal and vaginal examination will also be needed, to check for pelvic injuries. A urinary catheter can then be safely inserted and used to monitor the patient’s perfusion.

Repetition

Every check must be repeated again and again. Patients can ‘go off’ at any time and if they do it is commonly something simple like their airway, breathing or circulation that is causing the problem and which needs correcting.

Investigations like CT scans should only be undertaken once the patient’s condition is stable so a further check of ABC will be needed before the patient is moved.

Recording

All findings should be clearly recorded with the time when they were observed. It is often a gradual change in an observation which tells you more about what is happening to a patient than a single value.

Check

Before the patient leaves the resuscitation room, perform a final check. Every injury however small must have been found, measured and noted, and an appropriate care plan written. Once the patient has been transferred to the ward, it is all too easy for injuries to be missed and what might have been a trivial injury at the start (e.g. a dislocated finger) now may become a major impediment to returning to normal existence.

TIPS

- Rescue workers can give a good estimate of the energy involved in an accident

- Use ABC

- A sucker is better than a finger for clearing the mouth

- If there is one significant injury then look for more

- Working to a system allows the whole team to work quickly and efficiently

- Record all your findings clearly, looking for trends

- Keep going back to check ABC