Inguinal Hernia

Charles N. Paidas

Mark L. Kayton

Groin bulges, some of which represent inguinal hernias, are a common reason for visits to primary care physicians and emergency rooms and among the most frequent indications for surgical consultation. However, not all groin bulges are inguinal hernias. In this chapter we will present tactics to recognize, diagnose, and treat pediatric inguinal pathology. We will also discuss the complications of operations, a topic often minimized.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

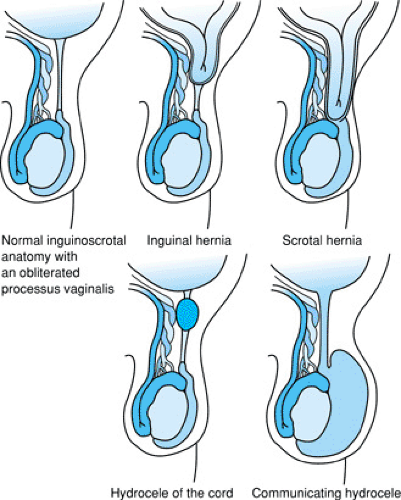

The origin of inguinal hernias lies in the embryology that is common to both males and females. Fetuses of both sexes have a genitoinguinal ligament that connects the developing urogenital ridges with the labioscrotal swelling. This genitoinguinal ligament becomes, in males, the gubernaculum testis, which presumably serves to guide the testis in its descent. In females, the genitoinguinal ligament becomes the round ligament of the uterus. In both sexes a tubular extension of the peritoneal sac develops ventral to either the gubernaculum or round ligament; this tubular outpouching is the processus vaginalis. If the processus vaginalis fails to obliterate, the stage is set for an inguinal hernia.

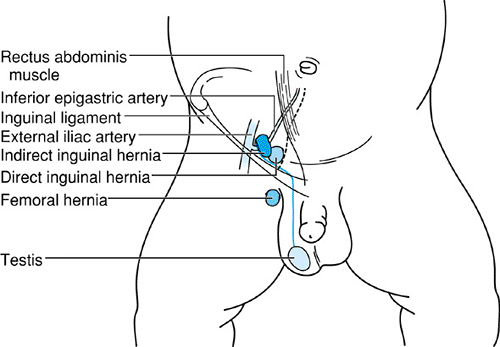

A processus vaginalis that contains intestine is called an inguinal hernia. One containing fluid is called a hydrocele (Fig. 345.1). Thus, hernias and hydroceles share a common embryology, but their treatment differs, as will be discussed later. Most inguinal hernias seen by pediatricians are congenital, indirect hernias, meaning that they are due to a patent processus vaginalis. Acquired, direct hernias are less common in childhood and stem from an inherent weakness in the musculature forming the inguinal canal rather than from a patent processus vaginalis. The congenital, indirect hernia arises lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. The acquired, direct hernia arises medial to the inferior epigastric vessels (Fig. 345.2). In the clinical practice of pediatrics, this distinction is somewhat academic, because indirect and direct inguinal hernias may have the same outward appearance, and the indications for referral and treatment do not differ. Ordinarily, in children, the type of hernia cannot be discerned until the time of operative dissection.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The clinical examination for hernia begins, in boys, with examination of the testes to determine whether both testes are descended into the scrotum. If not in the scrotum, the testicle itself, lying in the inguinal canal, may be the cause of the observed groin bulge.

Immobilizing the testicle in the scrotal sac with one hand, the examiner uses the other hand to palpate the external inguinal ring. A bulge may be detected. If not, efforts to make the child strain or cry or holding the baby in an erect upright position may produce a bulge. When a hernia can not be

discretely identified, sometimes the examiner will feel a thickened processus vaginalis, empty of intestine or other organs; this is referred to as the “silk glove sign” and is evidence of swelling of cord vasculature and is associated with freely reducible inguinal hernia.

discretely identified, sometimes the examiner will feel a thickened processus vaginalis, empty of intestine or other organs; this is referred to as the “silk glove sign” and is evidence of swelling of cord vasculature and is associated with freely reducible inguinal hernia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

An inguinal hernia can present with a bulge that extends to the external inguinal ring. This cranial extension prohibits the physician from fully grasping the neck of the hernia in his or her hand. A hydrocele, in contrast, may be wholly contained in the scrotum—the so-called noncommunicating hydrocele—and the examiner may be able to get around the top of the bulge with his or her fingers. This feature, when present, can help to distinguish some hydroceles from hernias. In many patients a noncommunicating hydrocele resolves without treatment, but most surgeons recommend surgery if the hydrocele persists at 12 to 18 months of age. A communicating hydrocele, in contrast, indicates that a continuous passage of fluid is occurring between the inguinal bulge and the peritoneal cavity, and it should be treated like a hernia.

Groin lymphadenopathy can be confused with an inguinal hernia. The relationship of the observed bulge to the external inguinal ring may help clarify the cause of swelling. Typically, if there are multiple inguinal groin nodes, they parallel the groin crease. Erythema or fluctuance of a groin mass may suggest presence of either abscess or strangulated inguinal hernia. Surgical referral should be made if the clinician is uncertain. Often, the history and clinical picture will help to differentiate the two, but operative exploration may be required if the diagnosis cannot be made clinically. If the swelling is determined to be an abscess, it should be drained under anesthesia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree