Informed consent in treatment and clinical research

Objectives

• Describe three basic legal concepts that led to the doctrine of informed consent.

• Discuss three major aspects of the process of obtaining informed consent.

• Compare informed consent as it is used in health care practice and in human studies research.

New terms and ideas you will encounter in this chapter

informed consent

battery

disclosure

fiduciary relationship

contract

disclosure standards

general consent

special consent

voluntariness

mental competence or mental capacitation

limited English proficiency (LEP)

capacity

competence

never competent

once competent

surrogate/proxy consent

legal guardian

best interests standard

substituted judgment standard

advance directives

assent

vulnerable populations

therapeutic research

institutional review board (IRB)

placebo

placebo effect

genetic information

right not to know

genomics

Topics in this chapter introduced in earlier chapters

| Topic | Introduced in chapter |

| A caring response | 2 |

| Trust | 2 |

| Character traits | 4 |

| Virtue | 4 |

| Principles approach | 4 |

| Autonomy | 4 |

| Beneficence | 4 |

| Nonmaleficence | 4 |

| Shared decision making | 11 |

| Health literacy | 11 |

| Rights and responsibilities | 11 |

Introduction

One important avenue to your success as a professional who has learned how to arrive at a caring response is to perfect the communication, listening, and interpretive skills necessary to honor informed consent. Informed consent is one of the cornerstones of the current U.S. and Canadian health care systems. Although the doctrine is the most formalized in these countries, it is an important concept in most Western health care systems. Whether with patients or research subjects, basic principles of respect for the person undergird informed consent. By going step by step through the ethical decision-making process, the importance of several aspects of informed consent in achieving your goals as a moral agent should become apparent. To inform your thinking, consider the story of Jack Burns and Cecelia Langer.

Reflection

Before you continue, take a minute to jot down your own response to this situation in regard to Cecelia’s and the other health professionals’ role in explaining the procedure. Can you think of anything else they could have done to help Jack?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

You will have an opportunity to revisit their situation as you study this chapter. You can begin to assess it by comparing it with any experience you may have had in which you were asked to give your informed consent for a treatment or diagnostic intervention or for participation as a research subject.

Reflection

If you have ever been asked to sign an informed consent form, could you understand it easily? Did you have to sign your name? Was someone on hand to answer questions you may have had at the time, or was there a telephone number where you could reach someone later? Did reading and signing the form make you feel more reassured about what you were about to experience? Why or why not?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

Now that you have a story to refer to and have considered your own experience, if any, you are ready to read on about informed consent.

The goal: a caring response

Informed consent is founded on basic legal-ethical principles. It entails a process of decision making and is both a process and a procedure. The idea is that you can perform your professional tasks better and in a morally praiseworthy way by bringing the person’s informed preferences into your plans. In summary, it is another tool to assist you in your skillful search for what a caring response entails.

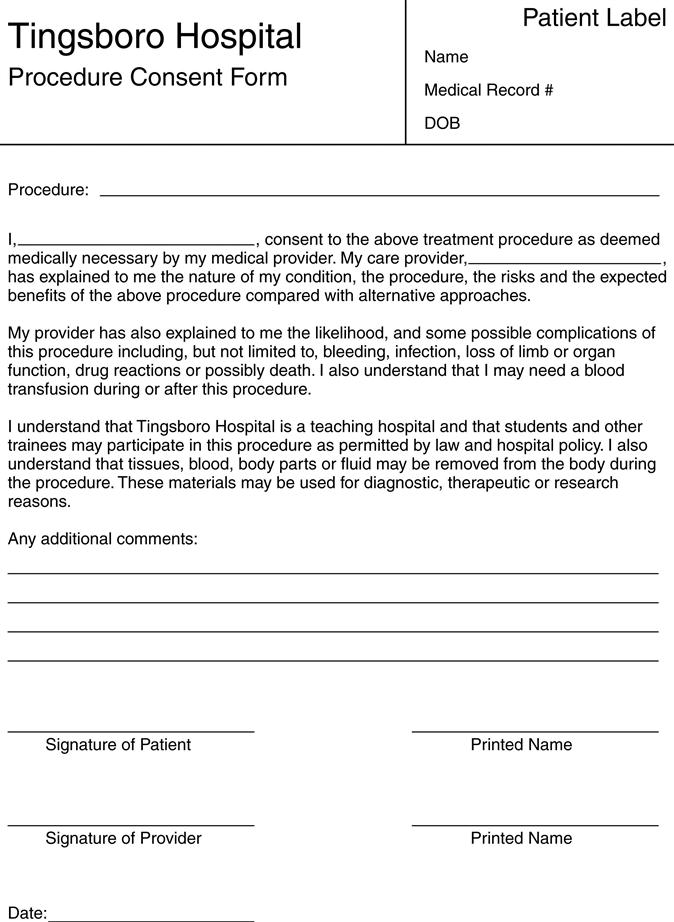

An example of a procedure consent document is provided for you in Figure 12-1. You can see from this example that an informed consent document spells out how the health professionals intend to use specific diagnostic or treatment interventions for the purpose of improving a patient’s condition. If designed appropriately, the document enables the person to become well informed before entering into the decision-making process. Informed consent, then, becomes a vehicle for protecting a patient’s dignity in the health care environment, the fundamental belief being that such consent should foster and engender trust between the health professional and the person receiving the services.

Reflection

What strengths and difficulties do you see in using the informed consent document in Figure 12-1 to foster the ideal of engendering trust?

1. Strengths

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

2. Difficulties

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

To help better understand how informed consent became so central to the health professional–patient relationship, we invite you to engage in the six-step process of ethical decision making, with your focus on informed consent.

The six-step process in informed consent situations

The most important thing to bear in mind as you analyze the specific informed consent–related challenges facing Jack Burns and Cecelia Langer is that the informed consent document, process, and procedures can support important ethical dimensions of the relationship. Its importance can be better understood by examining some aspects of the development of the idea.

Step 1: gather relevant information

As you may recall, when the six-step process was introduced in Chapter 5, we provided a long list of types of information that you would need to help you arrive at a caring response. We also warned you that other types of information could help as well, information not related to the patient’s specific situation. Information about the legal principles underlying informed consent is one example; elements of the process related to disclosure in informed consent are another. Let us examine each before identifying the type of ethical problem facing Cecelia Langer.

Relevant legal concepts that support informed consent

Among the most important legal concepts that have given rise to our thinking about informed consent are battery, disclosure, and the fiduciary relationship. The common law legal right of self-determination and constitutional right to privacy also are instrumental in legal thinking. You will consider self-determination for its ethical implications in another section of this chapter.

Battery, based on common law in the United States and other Western countries, is the act of offensive touching done without the consent of the person being touched, however benign the motive or effects of the touching.1

Disclosure guarantees the legal right of a person to be informed of what will happen to him or her. Several landmark legal cases have set precedents for current thinking on the importance of disclosure. Some practical challenges encountered regarding the appropriate standard of disclosure to use are discussed in the next section.

One of the earliest legal cases in the United States related to disclosure is Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital, which emphasized the relationship of disclosure to autonomy. This 1914 ruling stated that every human of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his or her body. For example, a surgeon who performs an operation without the patient’s consent is liable on the basis of the harm of nondisclosure.2 In the 1918 Hunter v. Burroughs case, the courts ruled that a physician has a duty to warn a patient of dangers associated with prescribed remedies so the patient is at liberty to decide whether or not the risk is worth it. Both rulings were early attempts by the courts to bring the patient’s preferences into decisions regarding what would happen to his or her own body.3

A third related legal concept is the idea of a fiduciary relationship. You were introduced to this idea in Chapter 2. In such a relationship, a person in whom another person has placed a special trust or confidence is required to watch out for the best interests of the other party. Most health professional–patient relationships are considered to be this type. The physician-patient relationship in the United States was ruled a fiduciary relationship in a 1974 case, Miller v. Kennedy, on the basis of the “ignorance and helplessness of the patient regarding his own physical condition.”4 This is, of course, an outdated understanding of the patient as “ignorant and helpless,” but that does not negate the basic idea of the need for faithfulness on the part of all health professionals.

The legal case that gave to posterity the term informed consent is Salgo v. Leland Stanford Board of Trustees (1957). This case stated that the physician violates his or her legal duty by withholding information necessary for a patient to make a rational decision regarding care. In addition, the physician must disclose “all the facts which materially affect the patient’s rights and interests and the risks, hazard and danger, if any.”5 With this ruling, the U.S. courts firmly wedded the notion of a patient’s autonomy with that of a health professional’s duty to warn of known danger or harm. In other words, the courts recognized that a caring response could not be achieved without those aspects of the interaction.

Relevant facts regarding the process of obtaining consent

Let us go on to some practical matters. Currently, the law supports that a patient should gain information about a proposed procedure and should have a voice in the decision. This constitutes a legal contract between patient and health professional. A contract, as you may know, is a legal agreement on which both parties claim to understand the situation they are agreeing to, including their respective responsibilities and rights.

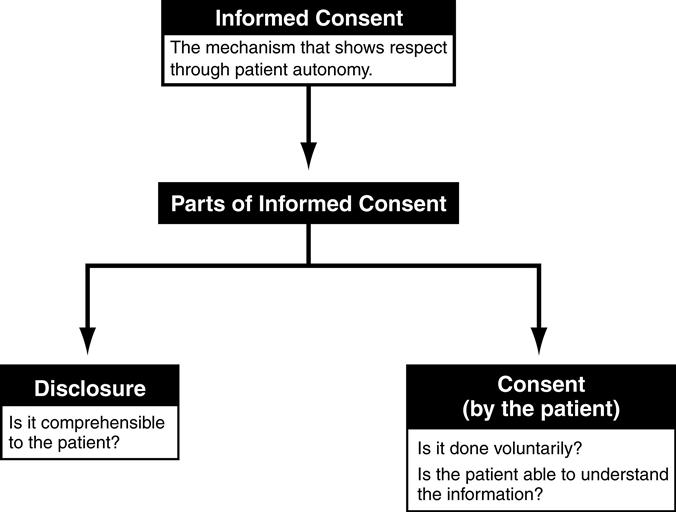

However, the law also recognizes that there may be several challenges in attempting to implement the consent process in a meaningful manner. Some challenges are related to the standard and amount of disclosure, whereas others are related to the person’s ability to grasp the situation (Figure 12-2).

Disclosure standards.

Disclosure standards are a key consideration. You have seen that a major legal concern is that a patient be informed. What disclosure standard can be used to judge that the level of information was sufficiently clear to be understood? One common suggestion is that “customary medical language” be the standard of disclosure. A second approach, which emphasizes the likelihood that patients will misunderstand technical terms used by the health professional, suggests that the standard be determined by what a “reasonable” person would need to make an informed decision. Finding one standard appropriate for everyone continues to perplex many. In fact, the courts have not settled on one standard, either. So, a third common approach is to conclude that the only alternative is to adopt an individualized standard for each patient.

Reflection

What are some practical barriers to institutionalizing any of the three suggested standards for an individual patient?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

Do you have any ideas about what an adequate approach to the issue of a disclosure standard fitting for all would be?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

A related aspect of ensuring adequate disclosure focuses on the appropriate amount of information that must be provided. In many health care settings, patients are directed to sign a standardized general consent form when they are admitted. You will recall that this happened to Jack and was the trigger for his first outburst of concern. The wording that appears on a typical general consent document states that a patient is consenting to routine services and treatment for his or her condition, the goal being the best care possible. In a teaching hospital, the person also is told that on entering the hospital she or he consents to become a participant in the hospital’s educational programs. Then, when certain invasive procedures are being considered, the consent is valid only when the person signs a special consent form. Recall that Jack also was asked to sign a special consent form for the imaging diagnostic test he would undergo; that became the source of his second outburst of frustration. The amount and type of information deemed adequate and appropriate in the special consent form may vary tremendously from one institution or procedure to another. Traditionally, medical and other relevant clinical information is presented in both verbal and written formats. Informed consent forms constitute the written document, but the verbal give and take gives the words life.

The goal is to take the patient’s background into consideration and determine the relative advantages and disadvantages of each decision choice for that patient’s future well-being. How each patient achieves understanding in the consent process is unique because we all learn and process information differently. Studies show that simple verbal and written consent procedures do not always yield adequate patient understanding.6 Many researchers are studying the effectiveness of alternative consent strategies, such as modified written forms to combat poor health literacy, and the inclusion of teaching aides and multimedia formats (e.g., video, interactive computer animation programs).

Anxiety and fear created by the unknown or general distrust of the health care system leave many patients with the sense that unfair advantage is being taken of them. When presenting informed consent documents, you should be found on the side of “taking too much time” with each patient, all the while being attentive to the patient’s cues regarding his or her level of comprehension. The best consent processes always uses shared decision making with the patient as the measure of success.

Voluntariness must be assured.

Informed consent assumes that a person voluntarily agrees to the procedure or process he or she is about to undergo. Within informed consent discussions, this is referred to as voluntariness. People speak or act voluntarily when no coercion compels them to do so against their own best interests and wishes. For this reason, individuals judged to be in vulnerable situations in which their ability to say “no” or “this is what I want” is compromised should be treated with special regard. As you may recall, Jack told Cecelia, the nurse practitioner, that he felt pressured to sign the consent form. A good informed consent process (in contrast to just an informed consent form) allows him either to increase his comfort level to the point of being willing to sign the form or to go away being clear why he chose to refuse treatment.

Reflection

What steps did Cecelia Langer and others take each step of the way to try to meet the criterion of voluntariness? Do you feel confident that they succeeded? Why or why not?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

One instance that tests the limits of voluntariness as a standard of respect for a person is the psychiatric practice of involuntary commitment for mental illness. This practice long has been condoned by the medical profession, and often by society as well. The increasing awareness of the importance of voluntariness, however, has created an environment in which such patients are able to maintain control over large parts of their treatment regimen, sometimes including whether to accept or reject medications.

Competence as a consideration.

Health professionals have a moral obligation to ascertain the level of a patient’s ability to grasp the situation. The ability to grasp it is called mental competence or mental capacitation, two important terms we describe more fully on page 262 of this chapter. For the purposes of our discussion now, please note that the idea of competence and capacity in the informed consent context allows us to address the assumption that individuals possess certain crucial knowledge without which they are unable to engage meaningfully in an act. Take, for example, the act of making a will. The person who does not know the general value of his estate or who does not have the mental capacity to recognize the existence of a rightful heir is not in a position to sign a valid will no matter what he or she may know about himself or herself or the world in general. These two pieces of information are so essential to the making of a will that unless one is in possession of them, one cannot properly dispose of one’s estate. In the same fashion, a person must be knowledgeable about certain crucial aspects of his or her health and the condition creating the problem to offer true informed consent. This formulation of competency is too narrow, however, when taken alone. It depends almost solely on the professional’s clinical evaluation, how much a person is told, and how much he or she can repeat back to you. This surely is not all you wish to know concerning a patient’s decision to give consent. A fundamental concern is whether the patient truly understands the nature of the illness and the basis for consenting or refusing intervention. For example, Jack may be having difficulty comprehending because of cognitive changes often associated with uremic poisoning. This is something to which Cecelia must pay close attention in the process of gathering relevant information about this patient. She will also need to obtain his medical record to determine whether any other conditions in his medical history, such as dementia or mental health disorders, may compromise his mentation.

Appelbaum and Grisso7 propose the following four relevant criteria for ascertaining the level of decision-making capacity that patients may be exhibiting:

4. The fourth level is the ability to reason about treatment options, which includes weighing the various values and relevant information to arrive at a decision.7,8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree