16 Inflammatory arthritis

Cases relevant to this chapter

21, 68, 70, 72, 75, 77–82, 85–86, 100

Essential facts

1. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common destructive inflammatory polyarthritis affecting 1% of the population.

2. Patients with persistent early morning stiffness and pain or swelling in at least three joint areas should be investigated for an inflammatory arthropathy.

3. In all cases of RA, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic therapy should be started as soon as possible.

4. Multidisciplinary management of RA helps patients to maintain long-term function.

5. Surgery may be required in RA to improve function and to relieve pain.

6. A diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis is often delayed by 8–10 years, because back pain is so common.

7. Reactive arthritis is a form of spondyloarthritis triggered by particular infections of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract.

8. Post-infectious arthritis (distinct from reactive arthritis) is associated with viral or bacterial infections.

9. In many patients with inflammatory arthritis, pregnancy exerts an immunosuppressive effect, with the exception of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which typically flares during pregnancy.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Definition

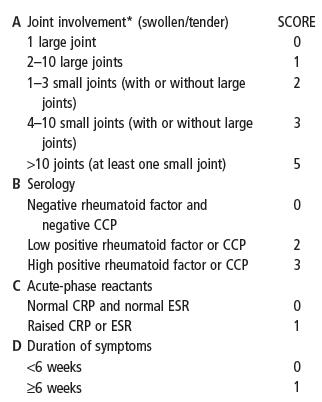

Classification criteria for RA were defined by the American Rheumatology Association (ARA) in 1987 and have been used extensively in research studies, showing high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of RA. These criteria (Box 16.1), particularly the four joint-associated clinical components (i.e. prolonged early morning stiffness with polyarticular symmetrical hand joint involvement), still give a useful guide to the most common clinical features of RA. However, these criteria have now been superseded by the 2010 EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism)/ACR (American College of Rheumatology) Classification Criteria. The 2010 criteria (Box 16.2) have been shown to have greater sensitivity and specificity in early RA.

Box 16.1

1987 American College of Rheumatology Criteria for classification of rheumatoid arthritis

Box 16.2

2010 EULAR/ACR classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis

Add the scores of categories A–D

A score ≥6 indicates DEFINITE RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Large joints: shoulders, elbows, hips, knees and ankles

Aetiology and pathogenesis

The cause of RA is unknown. There is evidence of a genetic contribution; individuals with certain HLA types are at increased risk of disease, and having an identical twin with the disease markedly increases the risk. As is discussed in Chapter 3 (Epidemiology and genetics of rheumatic diseases), several allelic variations of the HLA-DRB1 gene (such as HLA-DRB1 0401 and 0404) have been shown to be associated with disease development in different populations; these alleles share a common amino acid sequence in the DR-β chain (residues 70–74 – the ‘shared epitope’), although how this is involved in the disease aetiology remains an active research question. Although it is a risk factor, carrying an HLA genotype associated with RA or having an identical twin affected does not inevitably mean that disease will develop. Additional environmental processes must also be important. Smoking is certainly one of the contributory environmental processes associated with a significantly increased risk, particularly in patients carrying the shared epitope and who are seropositive for either RF or ACPA. Perhaps the most likely hypothesis, given the association with HLA-DR alleles, is that an aberrant T-lymphocyte response to an antigen results in activation of the immune system (including B-lymphocyte production of rheumatoid factor and ACPA) and an autoimmune driven inflammatory response focused on the synovium. The specific antigen involved in RA has not been clearly identified, although much interest has centred recently on the role of citrullinated proteins, following the identification of ACPA as a disease marker in a subgroup of patients with RA. Citrullination is the post-translation modification of the amino acid arginine (positively charged at physiological pH) to citrulline (uncharged) in a protein. Citrullination changes both the peptide sequence and the charge, and could therefore allow a novel peptide sequence to occur which could escape conventional tolerance mechanisms. Bacterial proteins can also be citrullinated – Porphyromonas gingivalis (a bacterium responsible for periodontitis, frequently found in smokers) unusually has an enzyme that can convert arginine to citrulline. Therefore, bacterial citrullination of self-proteins at sites of inflammation could also break tolerance.

Clinical features

History

As highlighted in Chapter 1 (Clinical history and examination), the characteristic clinical history feature of any inflammatory arthritis is early morning stiffness. In inflammatory arthritis this stiffness is present for at least 30 minutes, and usually for several hours on waking. It is often better in the afternoon but recurs with immobility and towards the evening (diurnal variation). Any patient who spontaneously offers a history of early morning stiffness needs thorough investigation to exclude an inflammatory arthropathy.

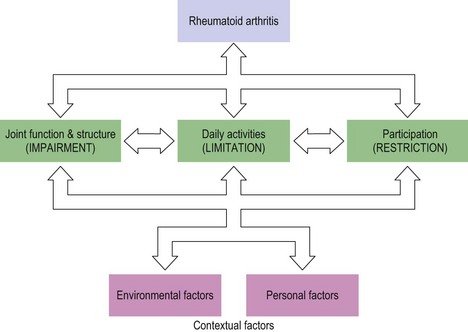

RA can cause significant disability through functional impairment, restricted participation and limitation of activities. It is important to enquire about the impact of the disease on the patient’s activities of daily living (ADLs) and occupational/recreational participation, so that these areas can be addressed appropriately. It is also useful to explore other patient-specific factors that could impact on a patient’s disability (Fig. 16.1). Extra-articular manifestations usually occur later in the disease course. However, they can occur early and a thorough review of all systems is also required when taking a history.

Examination

If allowed appropriate opportunity, the patient will usually have given the clinician enough information to make the diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis from the history. Examination then allows the clinician to confirm the diagnosis. Chapter 1 describes a system for comprehensive history-taking and screening examination of the musculoskeletal system and allows the clinician to identify involved joints that can then be assessed further with appropriate regional examination. The typical examination features in a patient presenting with RA are of swelling, warmth and joint-line tenderness of affected joints. Erythema is unusual. The pattern of joint involvement (Fig. 16.2) most frequently includes the wrists (carpi and distal radio-ulnar joints), the proximal interphalangeal joints (particularly index and middle fingers) and the metacarpophalangeal joints (again index and middle fingers). The feet should be examined because early foot involvement is associated with a worse prognosis and could indicate a need for more aggressive early treatment. Metacarpophalangeal and metatarsophalangeal squeeze tests, in which the heads of the metacarpals and metatarsals are squeezed gently (until the examiner’s fingernail just blanches) between thumb and middle finger, are sensitive indicators of underlying synovitis. The characteristic changes (including boutonnière and swan neck deformities of the fingers, ulnar deviation of the metacarpals or radial deviation of the wrist) are usually only seen in established disease.

A systemic examination looking for rheumatoid nodules (most often seen on the elbows) and extra-articular features should also be undertaken. RF-positive patients and those who are also homozygous for the HLA-DR shared epitope are at increased risk of extra-articular manifestations of the disease; these are also associated with worse joint disease and an increased mortality. These are discussed in Chapter 18 (Systemic complications of rheumatic diseases).

Early rheumatoid arthritis

There is robust clinical evidence that early aggressive treatment of patients with early RA (with combination disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment including methotrexate) improves the long-term outcome. A fast-track referral is recommended for patients with possible inflammatory arthritis, to allow early specialist involvement. Unfortunately, owing to limited resources, this is not always possible. The pattern of disease, involvement of the feet, a rising CRP level, positive RF and the presence of ACPA have all been shown to have predictive value in determining prognosis. There is also evidence that the presence of the shared epitope (especially homozygosity) predicts the development of more severe disease (see Chapter 3). Currently these are research findings and routine investigation does not include HLA typing in suspected RA.

Investigation

Imaging studies should include hand and foot radiographs (looking for peri-articular osteopenia or erosive changes; Fig. 16.3), a chest X-ray (para-neoplastic arthritis can be similar to RA, sarcoid can cause an inflammatory arthritis, particularly of the ankles, and latent tuberculosis and undiagnosed interstitial lung disease are relative contraindications to certain treatments). Other imaging modalities (ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) can also be helpful in supplementing clinical examination of the joints in early inflammatory arthritis. This can be particularly helpful where the findings are equivocal. Ultrasound imaging is increasingly used routinely by many rheumatologists in their clinical practice for this reason. MRI is more sensitive than ultrasonography for detecting both mild synovitis and early erosive changes, but is more costly and time-consuming. See Chapter 4 (Investigations) for further discussion of imaging modalities.

Treatment

NSAID responsiveness is frequently seen in RA, but this is only symptomatic therapy. This can be helpful diagnostically. However, monotherapy with NSAIDs has no impact on the progression of rheumatoid damage. Therefore, even if symptoms are controllable with NSAIDs, additional therapy with DMARDs is still required. The mechanism of action of NSAIDs is discussed in Chapter 5 (Medical management of arthritis). There is no difference in efficacy between conventional and cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2-specific NSAIDs, although the side-effect profile of COX-2-specific drugs is preferable, particularly with regard to the gastrointestinal tract (in younger patients with low risk of cardiovascular disease). Given the requirements in RA for long-term therapy at high doses, COX-2-selective treatments are frequently favoured in patients with gastrointestinal risk factors. All NSAIDs (with the possible exception of naproxen) are associated with an increased cardiovascular risk and should be used with caution in patients with other cardiovascular risk factors.

DMARD therapy should be initiated promptly. Conventional DMARDs are a diverse group of drugs, probably having an effect at a number of levels of the inflammatory cascade (for further details see Chapter 5, Medical management of arthritis). Weekly methotrexate (up to 25 mg/week) is a common first-line treatment, although daily sulfasalazine (up to 3 g/day) is another option. Both of these treatments are known to be efficacious, although the evidence for methotrexate is stronger and longitudinal studies show it is better tolerated. Folic acid (5 mg weekly or more frequently) has been shown to reduce the side-effects of methotrexate (mouth ulcers, gastrointestinal upset, and possibly hepatic and haematological disturbance). The authors’ practice is to prescribe Methotrexate on a Monday and Folic acid on a Friday to aid compliance.

Conventional analgesic pain management is also important, particularly in patients with secondary damage from previously active inflammation, as an adjunct to the anti-inflammatory approaches discussed above. Further discussion on the medical management of RA can be found in Chapter 5.

Non-pharmacological therapy

Treatment of RA is not solely pharmacological, and patient education, physiotherapy and occupational therapy are also core aspects of management. All patients should have access to education, physiotherapy and occupational therapy services at an early stage and throughout their disease; multidisciplinary management improves the chances of patients maintaining long-term function. Surgery may be required both to relieve pain and to improve function. Chapter 7 provides more detailed information on the non-pharmacological management of RA, and Chapter 8 on surgical management.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree