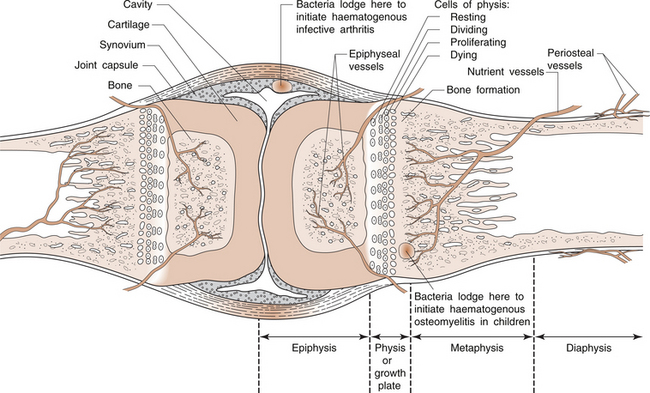

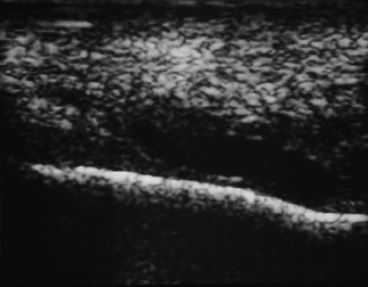

11 Sydney Nade In the musculoskeletal system there are three types of infection: • A primary process, in which the microorganisms attach to the target tissues, having reached them by the bloodstream (such as acute haematogenous osteomyelitis). • A potential process, in which an alternative portal of entry to the tissues has been made by breach of the integument, either by accidental trauma, or by intentional surgical incision (such as osteomyelitis after an open fracture). • An unwelcome process, occurring after entry to the tissues by one of the above routes, for which the methods used to eradicate the infection are likely to cause greater loss of function than the process for which the original surgical operation was performed (such as chronic osteomyelitis after hip replacement). • be repelled and eradicated, with restitution of the tissues to their normal state • cause such tissue damage that the host is unable to survive • be eradicated by the host but tissue destruction and inflammation lead to the formation of repair tissue that leaves a fibrous scar at the site of invasion (the most common outcome) • remain dormant in the tissues but there is ‘clinical resolution’ of the disease. The mere presence of microorganisms is not sufficient to produce disease. They must demonstrate an ability to invade the host tissues, to enter, multiply, spread and produce toxic substances. The body has defences against invasiveness and toxigenicity. The ability to produce a disease is known as pathogenicity. The comparative pathogenicity of various organisms is known as virulence. Very small numbers of virulent bacteria produce disease, whereas larger numbers are required of less virulent organisms. The invasiveness of microorganisms relates not only to the toxins that they produce, but also to enzymes, which may allow them to spread by tissue dissolution and protect them from host phagocytes. • haematogenous spread by bacteraemia or septicaemia from a primary site of colonization (skin, mouth, gut) if barriers to spread have been breached • direct access by puncture of the skin and deeper tissues following injury, with organisms carried in by the penetrating instrument • direct access at the time of elective surgery or following surgery for open injury Non-specific factors are those acting against a variety of microorganisms: • physiological, physical and chemical barriers at the portal of entry (skin or mucous membrane) • phagocytosis (intracellular killing of microorganisms) • the reticuloendothelial system The resistance of acquired immunity is a complex subject, but as reviewed in Chapter 1, there are two major subgroups: 1. humoral immunity, or the active production of antibodies; and 2. cellular immunity, in which certain lymphoid cells recognize material as foreign and initiate a chain of responses that permit them to destroy intracellular organisms. • neutralize toxins or cellular enzymes • have direct bactericidal or lytic effect • block the infective ability of microorganisms • agglutinate microorganisms, making them more susceptible to phagocytosis Cell-mediated immunity depends on the ability of sensitized lymphocytes to kill foreign cells by direct contact. Lymphocytes are found in lymphoid tissue (bone marrow, thymus, spleen, lymph nodes and lymph) and in the blood. In Chapter 1 we described how humoral immunity is mediated by B lymphocytes derived from stem cells in the bone marrow. These are stimulated by antigen to divide and form plasma cells, which then secrete antibodies against the antigen concerned. The other lymphocyte population, the T lymphocytes, are responsible for cellular immunity. The clinical patterns of acute osteomyelitis are different in infants, children and adults. The most likely explanation is that the blood supply and structure of bone in the three age groups is different (Fig. 11.1). You will recall from Chapter 5 that children have a well-defined growth plate (physis), while adults do not have a growth plate. In infants, a growth plate is present, but it is less well defined, and has some vessels that penetrate it and thereby connect the epiphysis and metaphysis of the bone. The physis is cartilaginous, and therefore capable of being ‘expanded’ by dividing and growing cells, whereas adult bone can only grow by apposition on its surface. At the junction of metaphysis and physis, small blood vessels are open-ended, growing towards the physis. At that point, the contents of the lumen can escape and lie adjacent to physeal cartilage. If an embolus of bacteria (septicaemia or bacteraemia) escapes from such a vessel, and the size of the inoculum is sufficient to cause an infection (a measure of virulence), and there is a tropism (attraction) of the pathogenic bacteria for cartilage, then an infection may be initiated. The absolute diagnosis of infection in bone requires that microorganisms be detected at a site in bone. The simplest way to confirm bone infection is to put a needle at the site of tenderness and to aspirate for pus. Any material collected should then be subjected to Gram staining and microbiological culture. However, this is not always possible and other investigations are usually necessary. Although bone is an easy tissue to image, changes in bone on plain radiographs, characteristic of infection, do not appear for several days after the infection has started. When present, the most typical change is the laying down of thin layers of bone on the periosteal surface (Fig. 11.2). By the time that occurs, the infective process may be well established and difficult to abort by treatment. Nevertheless, plain radiography should always be performed as it may show an alternative diagnosis. The best investigation to perform is ultrasound imaging. It is non-invasive, not painful, and shows an image of the tissues in real time. An anechoic zone adjacent to bone (that is, under the periosteum) means a collection of liquid and in the clinical setting confirms a diagnosis of osteomyelitis (Fig. 11.3). Furthermore, an aspirating needle can be guided by the ultrasound image to enter the liquid for the collection of a sample.

INFECTION AND THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

General principles of musculoskeletal infection

Portals of entry

Host defences against infection

Blood supply of bone

Acute infection of bone and joints

Diagnosis of acute bone infection

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

INFECTION AND THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue