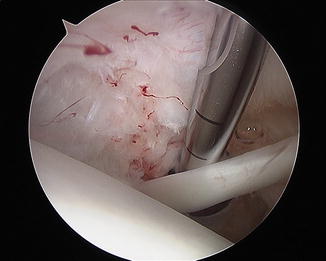

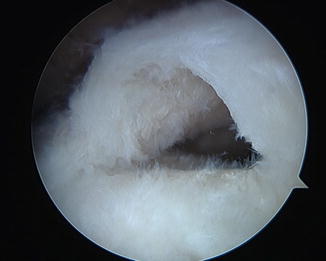

Fig. 16.1

Intra-articular view of a partial-thickness rotator cuff tear with significant intra-articular fraying

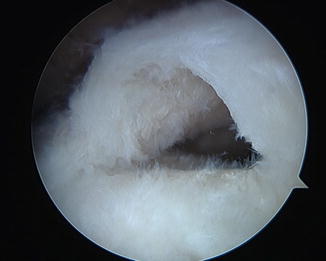

Fig. 16.2

Intra-articular view of a partial-thickness rotator cuff tear after debridement

Data from the MOON cohort [41] suggests patient expectations regarding physical therapy are the strongest predictor of nonoperative management failure. In other words if the patient believes therapy will work for them, then it probably will. If the patient does not think therapy will help them then it likely will not. Furthermore, they identified younger age, higher activity level, and abstinence from smoking as independent factors that predict failure of physical therapy programs for treatment of symptomatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Nonetheless, 6–12 weeks of a structured physical therapy program should be generally prescribed prior to offering surgery for patients with atraumatic, symptomatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears.

It should be recognized that the MOON cohort [40, 41] excluded acute and traumatic rotator cuff tears. Conservative management likely has a limited role in these patients. As mentioned, there is evidence that patients surgically treated within 3 months of an acute injury [34] have improved outcomes; some even advocate repair within 3 weeks of injury [29, 31]. Physical therapy, therefore, should have a limited role in the preoperative treatment of acute rotator cuff tears from traumatic events. A proposed treatment algorithm for management is displayed in Fig. 16.3.

Fig. 16.3

A proposed treatment algorithm for patients with imaging-confirmed, full-thickness rotator cuff tears

Partial-Thickness Tears

Operative management of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears is controversial. Management options for partial-thickness tears that fail physical therapy include tendon debridement, acromioplasty, and excision with repair. In general, symptomatic partial-thickness tears in patients that fail conservative management may be offered surgical intervention which can include debridement or repair depending on tear depth.

Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears involving more than 50 % of the affected tendon are often offered tear completion and subsequent repair. Dugas et al. [71] studied the insertional anatomy of the rotator cuff in 20 cadaveric shoulders. They determined that the mean medial-lateral diameter of the supraspinatus insertion is 14.7 mm. Symptomatic high-grade partial-thickness rotator cuff tears (defects >5–7 mm) who fail conservative treatment may be offered tear completion and repair with good expected results. There is evidence that symptomatic partial-thickness tears involving >50 % of the tendons are best treated with conversion to a full-thickness tear and repair [72, 73]. Webber et al. [72] compared 32 patients with partial-thickness RTC tears treated with debridement compared to 33 patients treated with conversion to full-thickness tears followed by repair. All tears in their series involved >50 % of the affected tendon defined by a >6 mm RTC defect; they found reoperation to be significantly higher in patients who underwent debridement alone. They also reported higher UCLA scores in patients treated with repair of partial rotator cuff tears compared to those treated with debridement. Bursal-sided tears may be resistant to nonoperative care and subacromial decompression alone [74]. Kim et al. [75] reported similar outcomes in patients undergoing repair of bursal- and articular-sided partial-thickness tears at a mean follow-up of 36 months. Other techniques have also been described for repair of partial-thickness tears. These include transtendinous PASTA (partial articular-sided tendon avulsion) repair [76] and the all-inside articular-sided rotator cuff repair as described by Spencer [77]. The indications for repair using these other techniques are the same as described above for completion and repair of the tear, and no real data exists demonstrating superiority of one technique over another.

Partial rotator cuff tears that effect <50 % of the tendon may be offered debridement if conservative management fails [78, 79]. Partial-thickness tears result in significant intra-articular fraying that can irritate the glenoid labrum or the long head of biceps tendon with shoulder motion. This is not an uncommon scenario in young active/athletic patients with partial rotator cuff injuries (Figs. 16.4 and 16.5). Debridement of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears in elite throwers has been demonstrated to have good results in 75 % of patients including returning to competitive pitching [80]. Repair of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears in the throwing athlete is rarely indicated as shoulder stiffness may ensue [79]. Patients with partial-thickness rotator cuff tears involving <5–7 mm of the tendon footprint who fail physical therapy may be offered debridement; careful inspection and possible repair of other intra-articular structures in the throwing athlete may also be indicated.

Fig. 16.4

Full-thickness rotator cuff tear

Fig. 16.5

Full-thickness rotator cuff tear status postrepair

Summary

The indications for rotator cuff repair are still evolving. The prevalence of cuff pathology in asymptomatic patients suggests that many patients can do well without surgery. In addition, the body of evidence is improving regarding indications for surgery. Factors such as patient activity level and patient expectations have been proven to be important considerations for recommending treatment. The rimportance of structural factors such as size of tear and characteristics on MRI remains controversial and requires more investigation.

References

1.

Kannus P, Jozsa L. Histopathological changes preceding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(10):1507–25.PubMed

2.

Milgrom C, et al. Rotator-cuff changes in asymptomatic adults. The effect of age, hand dominance and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(2):296–8.PubMed

3.

4.

Reilly P, et al. Dead men and radiologists don’t lie: a review of cadaveric and radiological studies of rotator cuff tear prevalence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(2):116–21.PubMedPubMedCentralCrossRef

6.

Petersson CJ. Ruptures of the supraspinatus tendon: cadaver dissection. Acta Orthop. 1984;55(1):52–6.CrossRef

7.

Ozaki J, et al. Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70(8):1224–30.PubMed

8.

Teefey SA, et al. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff a comparison of ultrasonographic and arthroscopic findings in one hundred consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82(4):498.PubMed

9.

Sher JS, et al. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77(1):10–5.PubMed

10.

11.

Yamanaka K, Matsumoto T. The joint side tear of the rotator cuff. A followup study by arthrography. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;304:68–73.PubMed

12.

13.

14.

Mall NA, et al. Symptomatic progression of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective study of clinical and sonographic variables. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(16):2623–33.PubMedPubMedCentralCrossRef

15.

Cofield RH, et al. Surgical repair of chronic rotator cuff tears. A prospective long-term study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):71–7.PubMed

16.

17.

18.

Pai VS, Lawson DA. Rotator cuff repair in a district hospital setting: outcomes and analysis of prognostic factors. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):236–41.PubMedCrossRef

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree