Humeral Shaft Fractures: Intramedullary Nailing

Craig S. Roberts

Brent M. Walz

Jonathan G. Yerasimides

Indications/Contraindications

The precise role for intramedullary nailing in the treatment of humeral shaft fractures is not defined (1). Although most humeral shaft fractures that require surgery are usually treated with plating, there remains a quiet optimism that newer approaches and implants for humeral nailing will lower the complication rate and thereby improve healing rates and patient outcomes.

Anatomic differences between the long bones of the lower extremity (tibia and femur) and the humerus narrow the indications for humeral nailing. The medullary canals of the femur and tibia extend distally into their respective metaphyses. In contrast, the humeral canal ends at the metaphysis. The isthmus of the femur is at the junction of the proximal and middle thirds, while the isthmus of the humerus is at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the bone. The bone at the distal end of the medullary canals of the femur and the tibia is soft, metaphyseal bone, whereas the distal bone of the humeral canal is hard, diaphyseal bone. These anatomic differences highlight the need for newer design features and technologies for humeral nails that will differentiate them from tibial and femoral nails.

Besides anatomic differences, problems with classic antegrade (from the shoulder) nailing have limited its application. Shoulder pain following antegrade nailing may be unresolvable and has many similarities to anterior knee pain associated with tibial nailing. Nonunions associated with antegrade humeral nailing appear to be unique and more recalcitrant than those caused by other treatment methods (2). Furthermore, the humerus, unlike the tibia or femur, does not tolerate distraction at the fracture site. These formidable challenges with antegrade nailing are not resolved using standard approaches and available implant technology.

Humeral nailing is attractive because it is minimally invasive, can be done relatively quickly, and avoids the morbidity of extensive incisions. Because antegrade nailing has many potential complications, retrograde (from the elbow) nailing may be an attractive option for some patients. This chapter will review the techniques of both retrograde and antegrade nailing, detail possible complications, and provide a rationale for clinical application of these techniques.

Intramedullary nailing of the humerus can be performed either from the shoulder or the elbow. These two approaches enable the surgeon to nail diaphyseal fractures from the proximal fourth to the distal fourth of the humerus. The approach chosen should be based on Küntscher’s principle of nailing from an insertion site as far from the fracture site as possible. Proximal shaft fractures should be nailed in a retrograde fashion; conversely, distal shaft fractures should be nailed in an antegrade fashion. Midshaft fractures may be approached from either end of the humerus. In adults, interlocking nailing is preferred over flexible nailing, which is occasionally used in pediatric fractures.

The surgeon should be familiar with both antegrade and retrograde approaches. The type of the fracture and its location, as well as overall condition of the patient, must be understood for selection of the correct approach and implant.

The indications for intramedullary nailing of the humerus are displaced transverse fractures of the diaphysis, segmental fractures, floating elbow injuries, pathologic fractures, fractures associated with thermal burns, and fractures in the polytrauma patient. A pathologic or impending pathological fracture may be the overall best indication for humeral nailing. Relative contraindications to intramedullary nailing include open fractures, fractures with associated radial-nerve palsy, long spiral fractures, open epiphyses, a narrow intramedullary canal, and prefracture deformity of the humeral shaft.

Preoperative Planning

Demographics, medical history, and information regarding the circumstances and mechanism of injury should be obtained. The arm should be carefully examined for neurovascular injuries. In general, intramedullary nailing should be avoided with open humeral fractures with or without obvious nerve palsy. Open humerus fractures are notorious for radial nerve interposition or laceration (3). Patients who are unable to cooperate with a neurological examination because of a head or spinal cord injury generally should undergo an open plating procedure with radial nerve exploration

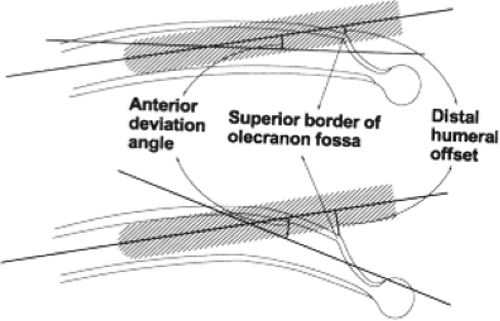

Standard radiographs include anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the entire humerus. Because the arm should not be manually rotated through the fracture site in an attempt to obtain a lateral view, a transthoracic lateral is the preferred view. The diameter of the medullary canal size, canal length, and anterior deviation of the distal canal are measured on the lateral radiograph (4). Intramedullary canal sizes vary among patients, and therefore, these measurements provide an estimate for the dimensions of the nail. Measurements can be performed either manually or with a digital radiography system. The anterior deviation or distal humeral offset is visualized preoperatively to determine the relationship between the alignment of the humeral canal and the entry portal (Fig. 6.1) (4). With a small anterior deviation (distal humeral offset), the entry portal for retrograde nailing should be more distal and include the superior border of the olecranon fossa, which will require a longer bony defect. Conversely, if the anterior deviation (humeral offset) is large, the entry portal will need to be more proximal and will likely require a smaller length portal. The entry portal is usually 1.5 to 2.0 cm proximal to the olecranon fossa. Smaller canals require smaller nails and may be more susceptible to iatrogenic comminution. Multiplanar computed tomography (CT) can be helpful if there is any suspicion of fracture extension or a second fracture at a different level. Once adequate films are taken, the arm should be immobilized in a coaptation splint and sling (Fig. 6.2). The two most important preoperative decisions regard (a) whether a retrograde or an antegrade approach is indicated, and (b) if a retrograde approach is selected, the appropriate starting point as based on the patient’s anatomy. The majority of displaced closed fractures can be surgically addressed in the first 10 days after injury.

Surgical Technique for Retrograde Interlocking Nailing

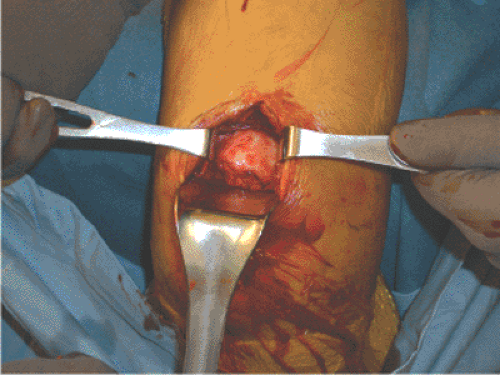

General endotracheal anesthesia is used, preoperative antibiotics are given, and the patient is positioned either in the lateral decubitus or prone position. We prefer the prone position (Fig. 6.3) and have found that an upper paint-roller type support is helpful in preventing traction injury to the brachial plexus, facilitating access to the olecranon fossa, and holding the arm in approximately 80 degrees of abduction. A 6-cm posterior incision, starting from the olecranon, is made in line with the humeral shaft (Fig. 6.4). The triceps tendon is split in line with its fibers and carried directly down to bone (Fig. 6.5). The olecranon fossa is identified and cleared of muscle with an elevator. The starting point for entry into the medullary canal must be individualized based on the anatomy of the distal humerus in the coronal plane and adjusted more proximally or distally, as previously described. The axis of the humerus is also in line with the lateral aspect of the olecranon fossa (Fig. 6.6). Using a drill guide, multiple, small, drill holes are made (Fig. 6.7) that outline the entry portal directly in line with the shaft of the humerus. These holes are then connected with a large drill bit and small rongeur to create an oval hole (Fig. 6.8). A router can also be used to enlarge the entry portal. Reduction of the fracture usually involves gentle traction on the distal humerus and correction of the coronal plane displacement (varus-valgus rotation). A ball-tip guide wire is inserted across the fracture site and confirmed fluoroscopically (Fig. 6.9A) and the canal is sequentially reamed up to an appropriate diameter, usually 1.0 to 1.5 mm

greater than the size of the nail (Fig. 6.9B). While reaming the canal, the surgeon must stay in line with the humeral shaft.

greater than the size of the nail (Fig. 6.9B). While reaming the canal, the surgeon must stay in line with the humeral shaft.

Figure 6.3. The patient is positioned in the prone position with the elbow flexed over the side of the table. |

Figure 6.4. The skin incision is made for the entry portal from the tip of the olecranon to a point 6 cm proximal to the olecranon fossa. |