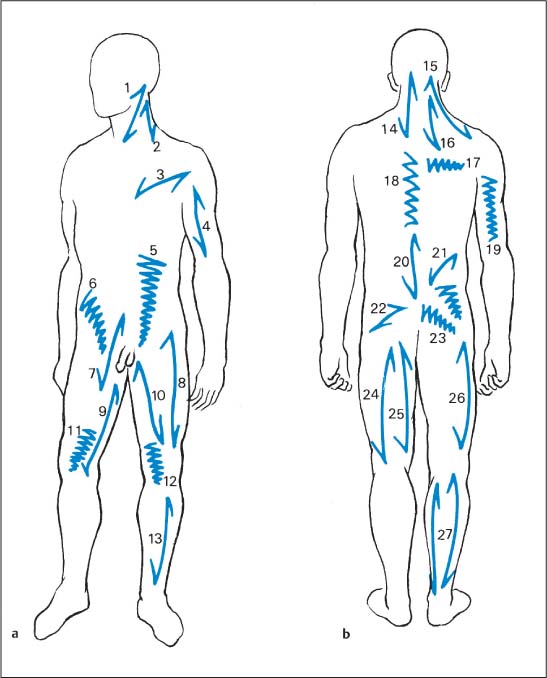

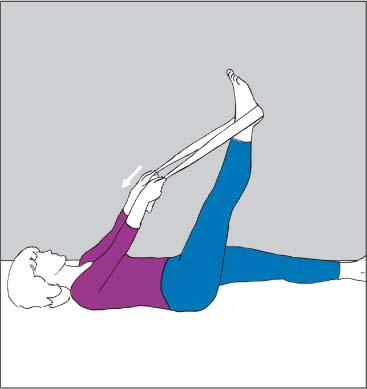

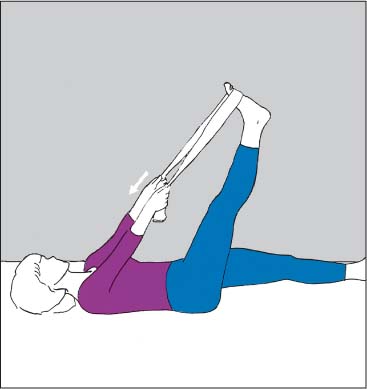

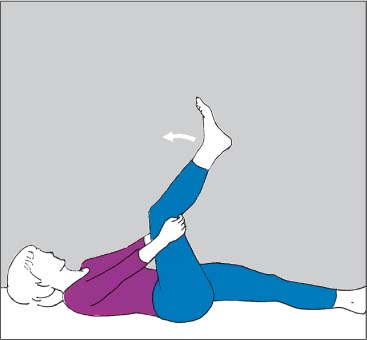

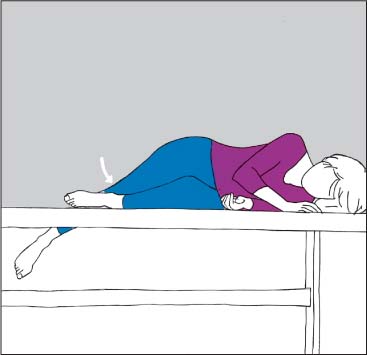

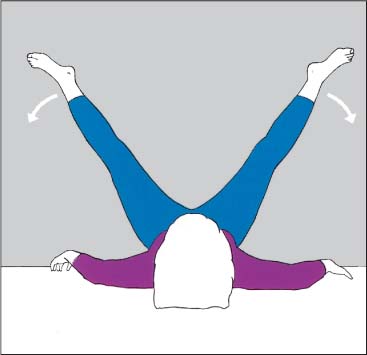

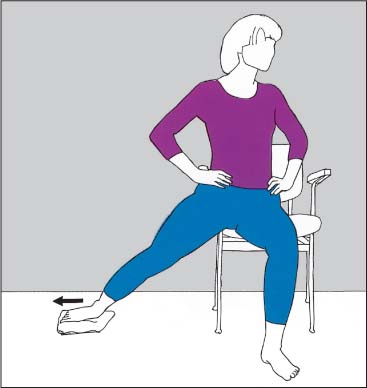

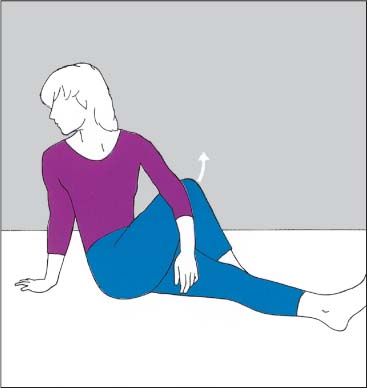

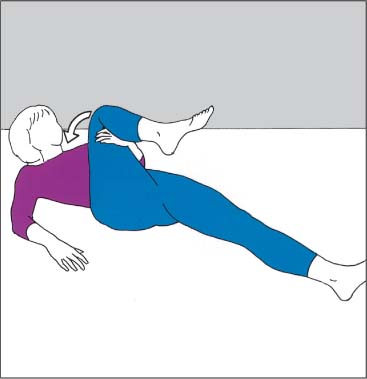

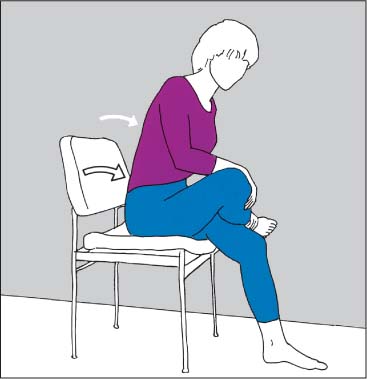

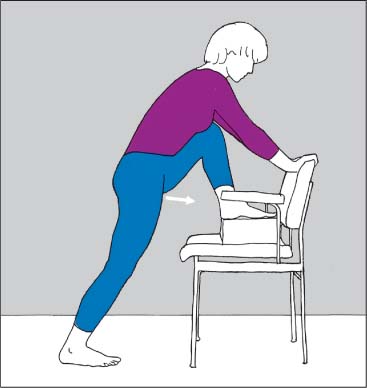

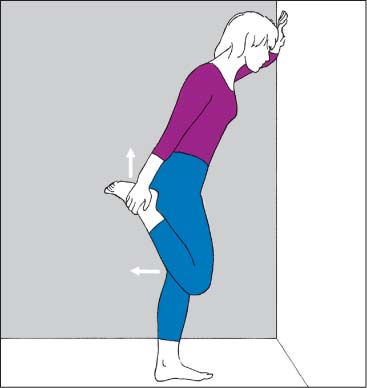

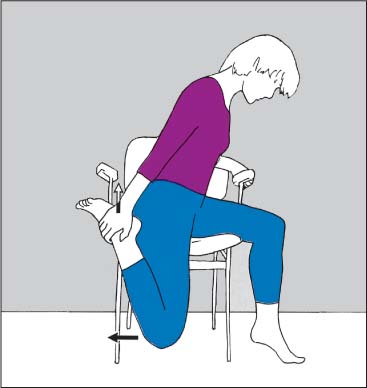

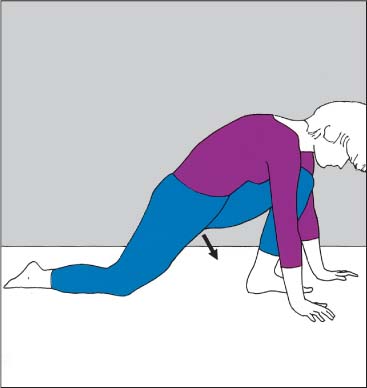

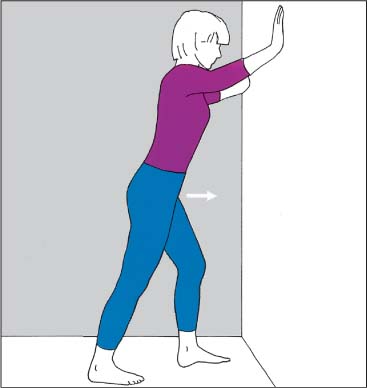

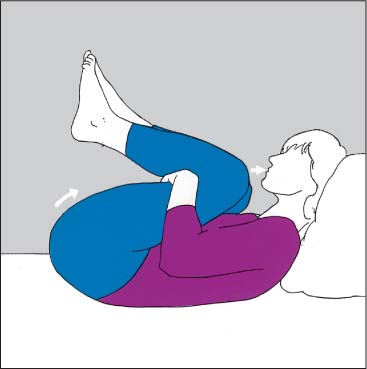

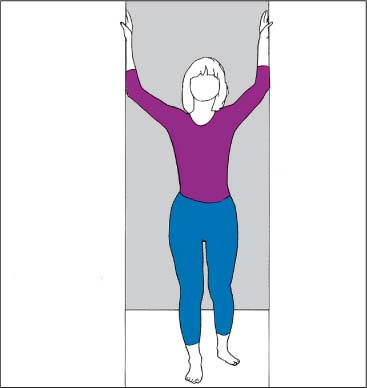

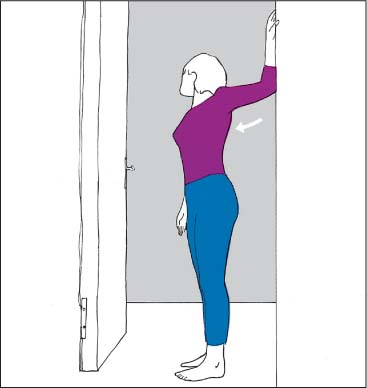

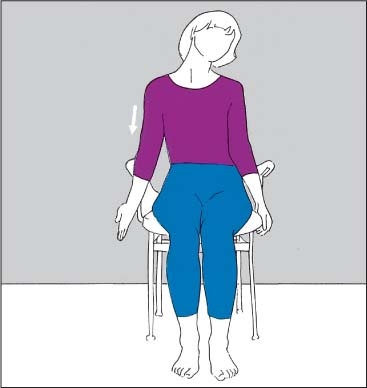

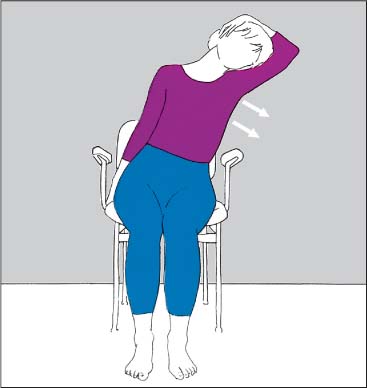

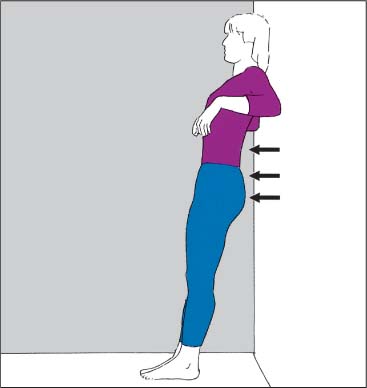

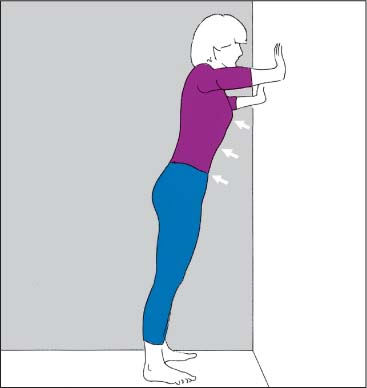

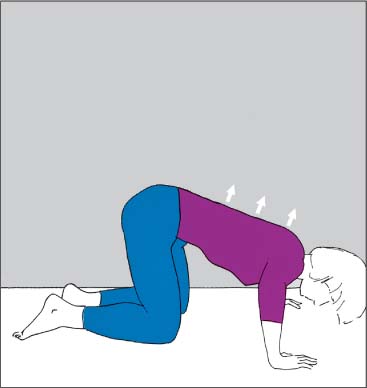

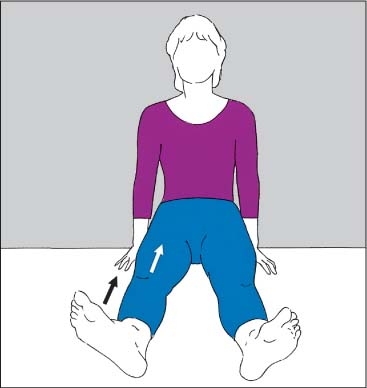

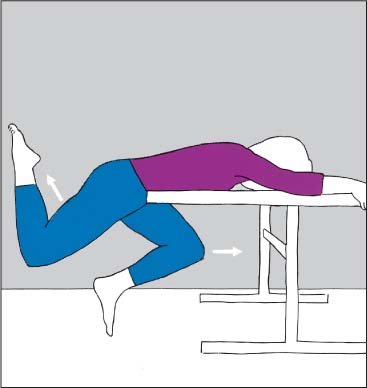

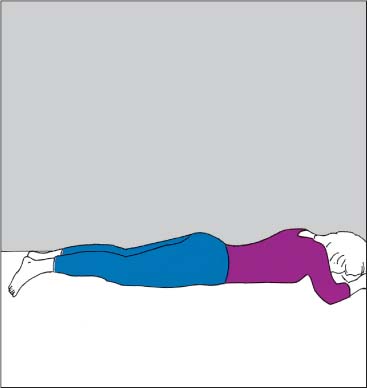

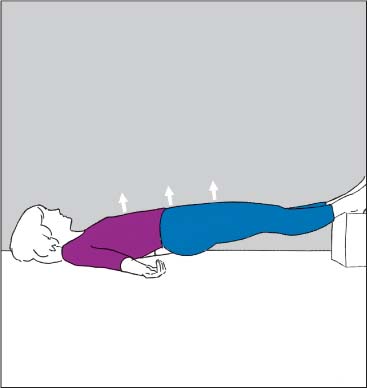

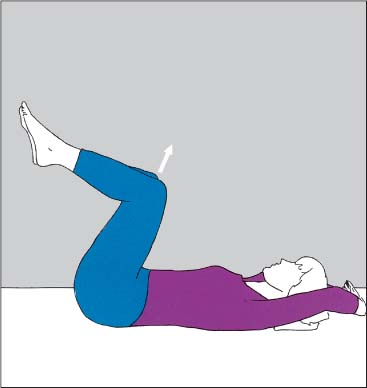

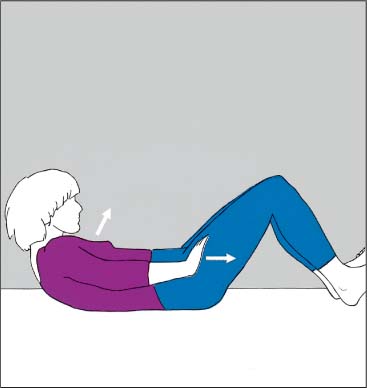

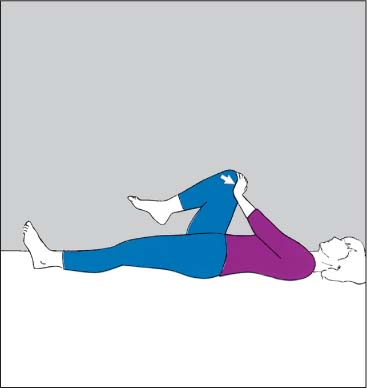

19 Home Exercise Program Today, exercises are considered an integral part of patient management in manual medicine. The goal of treatment is to maximize patient function and independence, while minimizing pain and recurrences of pain by specifically addressing the structural, biomechanical and functional deficits arising from the various joint and tissue dysfunctions. In order to prescribe the appropriate exercise regimen for a particular patient, the specific structural and functional deficits need to be elucidated through a detailed structural and functional examination so as to determine the global, regional and specific segmental deficits. From the outset, patient goals and the various bio-psycho-social aspects should be considered when establishing the exercise prescription, including the final home exercise program. There is ongoing discussion about the usefulness of manual medicine management and exercise therapy for various musculoskeletal disorders, either in isolation (one approach) or in combination (manual medicine and exercise combined). Supervised exercise therapy—i. e. “active” rather than passive therapy, modality-emphasized physical therapeutic measures—has become part of the most recent recommendations for the treatment of low back pain (Koes et al., 2006): In the management of osteoarthritis, for instance, the Ottawa Panel (2005) recommend the use of therapeutic exercises, either alone or combined with manual therapy. Beyond these and many other guidelines, there continues to be an ongoing discussion in the literature as to the advantages and disadvantages, indications, exercise types and preferences, mechanisms and outcomes of exercise in general (Hayden et al., 2005). In addition to a generalized exercise regimen for aerobic cardiovascular and muscular conditioning, specific exercises to address muscle length (flexibility) and strength (power) are utilized in manual medicine. It is important that the exercise prescription for each patient is developed on an individual basis (specific selection of the particular exercises and their sequence, repetition and overall number of sets). The various exercises are a logical extension of and complement for the manual medicine treatment. A number of various treatment regimens have been presented by various practitioners to improve flexion (Williams, 1953) and extension (McKenzie, 1981). Isaac and Bookhout (2002) make specific reference to McKenzie’s approach and specific non-neutral segmental (somatic) dysfunctions, in particular the flexion, rotation and side-bending dysfunctions (FRS-dysfunctions noted in the osteopathic literature). Bookhout presents a practical and rational approach to restoring normal neuromotor control by addressing the muscle imbalances associated with frequently observed abnormal movement patterns and specific segmental joint (somatic) dysfunctions. Of particular importance in the concept of muscle imbalance are those presented by Janda (1980; 1977; 1986; 1994) and Lewit (1995). This chapter contains a series of home exercises that can be given to patients. These exercises fall into two broad categories: 1. Those muscles or muscle groups that need to be stretched (typically the tonic, slow-twitch fiber muscles) and 2. Those muscles or muscle groups that need to be strengthened (typically the phasic, fast-twitch fiber muscles). In general, it has been empirically learned and practiced (and thus awaits further good research, for instance) that when a muscle imbalance has been diagnosed the stretching of the shortened muscles should be done first before the strengthening. The rationale for this sequence is that abnormal muscle patterns may provide a negative-vicious-cycle feedback loop, where the strengthening of the already strong muscles is thought to further exacerbate the already existing muscle imbalance. Some of the key points (no more than five) to remember when prescribing a home exercise program may include: 1. Have the patient perform the exercises under supervision until he is ready to perform them adequately and on his own. 2. Start low (one or two exercises to start with) and go slow (addition of new exercises). 3. Check to see what other exercises the patient may already be doing from previous treatment regimens (avoid duplication or exacerbation). 4. Evaluate patient’s ability to perform the exercises correctly over time, from visit to visit and then independently, with appropriate interval-based monitoring. 5. Assist with appropriate motivation for the patient to continue on an independent home exercise program. As with many other aspects of health and function, it is often not one single factor that decides the outcome. It would be ideal if not only the medical aspects of the patient’s well-being are being addressed but also thorough consideration be given to dietary considerations, general fitness and physical performance, activities of daily living and vocational/ergonomic considerations, as well as the choice of appropriate and meaningful leisure activities. Fig. 19.1 Overview of the tonic (postural) ( 1 Sternocleidomastoid 2 Scalene 3 Pectoralis major 4 Biceps brachii 5 Rectus abdominis 6 Abdominal oblique 7 Iliopsoas 8 Rectus femoris 9 Gracilis 10 Adductors 11 Vastus medialis 12 Vastus lateralis 13 Tibialis anterior 14 Longissimus cervicis 15 Trapezius (descending portion) 16 Levator scapulae 17 Rhomboid 18 Longissimus dorsi 19 Triceps brachii 20 Longissimus dorsi 21 Quadratus lumborum 22 Piriform 23 Gluteal 24 Biceps femoris 25 Semitendinosus 26 Tensor fasciae latae 27 Triceps surae (soleus and gastrocnemicus) The ideal outcome is one in which the goals of both patient and physician are congruent and can be fulfilled to the greatest possible extent, taking into consideration all aspects of the bio-psycho-social-spiritual model. Fig. 19.2 Stretching of the posterior thigh muscles. Instructions: – Wrap towel around heel. – With knee straight, bring leg up toward you as far as possible. – Against resistance, push leg in opposite direction with maximal contraction. – Bring leg further toward you. Fig. 19.3 Stretching of the posterior thigh muscles and calf muscles. Instructions: – Wrap towel around the tip of the foot. – With knee extended, bring leg up toward you as far as possible. – Against resistance, push leg in opposite direction with maximal contraction. – Bring leg further toward you. Fig. 19.4 Stretching of the posterior thigh muscles. Instructions: – Bend leg at the knee and hold it in place with hands. – Straighten leg to a point where a pulling type of pain sensation is perceived in the posterior muscles. – Relax. – Repeat further straightening. Fig. 19.5 Stretching of the lateral thigh muscle. Instructions: – With the leg closest to the table bent, lie on one side across the table at an angle. – Extend the other knee and drop that leg behind the posterior edge of the table. – Bring leg back up. – Relax and drop leg further. Fig. 19.6 Stretching of the medial thigh muscles. Instructions: – Lie supine with buttocks and posterior thighs placed against the wall. – With knees straight, let legs move apart slowly. – Contract medial thigh muscles (as if wanting to bring legs together). – Relax. Fig. 19.7 Stretching of the medial thigh muscles. Instructions: – With the knee straight, place one leg to the side, push medial foot margin against the floor. – Relax. – Allow leg to glide further outward. Fig. 19.8 Stretching of the deep gluteal muscles. Instructions: – Pull knee toward opposite hip. – Against some resistance, push knee outward. – Relax. – Pull knee closer toward the opposite hip. Fig. 19.9 Stretching of the deep gluteal muscles. Instructions: – Pull knee with hand toward the opposite shoulder. – Against resistance, contract maximally as if wanting to move knee away from shoulder. – Relax. – Pull knee further toward the opposite shoulder. Fig. 19.10 Stretching of the deep gluteal muscles. Instructions: – Pull knee toward opposite hip. – Straighten upper body while inhaling simultaneously. – While exhaling, lean forward with straight upper body. – Further straighten trunk, again while inhaling. – Repeat stretch. Fig. 19.11 Stretching of the hip flexor muscles. – Move pelvis forward over the extended support leg (the leg making contact with the floor). Fig. 19.12 Stretching of the hip flexor and long knee extensor muscles. Instructions: – Pull leg up behind you. – Against resistance, straighten knee. – Relax. – Pull leg up further. Fig. 19.13 Stretching of the hip flexor and long knee extensor muscles. Instructions: – Pull leg up behind you. – Drop head forward. – Straighten knee against resistance. – Relax. – Pull leg up further. Fig. 19.14 Stretching of the hip flexor and long knee extensor muscles. Instructions: – Assume position similar to that of starting for a sprint. – Push straightened (posterior) knee toward the floor. – Relax. – Extend hip further. Fig. 19.15 Stretching of the calf muscles. Instructions: – Lift heel of the posterior leg off the floor. – Push heel flat against the floor. – With the back straight, move trunk slowly forward. – Lift heel off the floor, and then push it down again. – Stretch further. Fig. 19.16 Stretching of the lower back extensor muscles. Instructions: – Sit with legs slightly apart and feet raised (e. g., on books, etc.). – Lean upper body forward. – Inhale. – Exhale while pulling the arms below the chair. – Inhale and exhale. – Pull arms further below the chair. Fig. 19.17 Stretching of the lower back extensor muscles. Instructions: – Bring knees toward chin until pelvis begins to lift off the floor. – Press thighs against arms and inhale. – Exhale and relax. – Bring knees further toward your chin. Fig. 19.18 Stretching of the chest muscles. Instructions: – Walking position. – Press hands against door frame. – Relax. – Lean upper body forward. Fig. 19.19 Unilateral stretching of the chest muscles. Instructions: – Stand sideways to the door frame; rest forearm against the frame. – Press forearm against door frame. – Rotate trunk away (in small rotational steps) with the forearm remaining stationary. Fig. 19.20 Stretching of the neck and shoulder muscles. Instructions: – Bend head to one side. – Rotate arm outward and push it toward the floor. – Inhale and lift shoulder. – Exhale and pull arm toward the floor. Fig. 19.21 Stretching of the neck and shoulder muscles. Instructions: – Bend head to one side (i. e., left) and hold in place with one hand. – Grasp chair with the other hand. – Lean trunk to the same side (i. e., left). – Move back somewhat toward the original position and place hand on the chair closer to the floor. – Repeat side-bending of the trunk. Fig. 19.22 Strengthening of the shoulder blade muscles. Instructions: – Lean with shoulder blades against the wall at an angle. – Push trunk off with the elbows, while maintaining normal lumbar lordosis (do not arch back). Fig. 19.23 Strengthening of the shoulder blade muscles. Instructions: – Place fingertips against the wall at shoulder level. – Push body off slightly. – Maintain normal lumbar lordosis (do not arch back). Fig. 19.24 Strengthening of the shoulder blade muscles. Instructions: – Rest on knees and hands. – Slowly drop upper body between hands. Fig. 19.25 Strengthening of the anterior thigh muscles. Instructions: – Rotate leg slightly outward. – Keep knee straight. – Pull great toe and foot toward you. – Pull kneecap toward you. – Contract anterior thigh muscles. Fig. 19.26 Strengthening of the gluteal muscles. Instructions: – Lift one leg (with knee bent) up toward the horizontal while pushing the opposite leg under the table top. Fig. 19.27 Strengthening of the gluteal muscles. Instructions: – Press heels together. – Contract buttock muscles maximally. Fig. 19.28 Strengthening of the gluteal muscles. Instructions: – Raise heels and rest them on support. – Contract buttock muscles and simultaneously lift pelvis and lower back off the floor. Fig. 19.29 Strengthening of the abdominal muscles. Instructions: – Push knees toward the ceiling. – At the same time, lift pelvis slightly off the floor. Fig. 19.30 Strengthening of the abdominal muscles. Instructions: – Pull toes toward you while pressing heels against the floor. – Rotate arms slightly inward. – Bend hands upward and push in direction of feet. – Lift head and shoulders off the floor. Fig. 19.31 Strengthening of the abdominal muscles. Instructions: – Bend knee and press against resistant hand. – Lift head slightly off the floor. Abrahams M (1967). Mechanical behaviour of tendon in vitro. A preliminary report. Med Biol Eng 5(5):433–43. Ahmed SK, Egginton S, Jakeman PM, Mannion AF, Ross HF (1997). Is human skeletal muscle capillary supply modelled according to fibre size or fibre type? Exp Physiol. 82(1):231–234. Aker PD, Gross AR, Goldsmith CH, Peloso P (1996). Conservative management of mechanical neck pain. Systematic overview and metaanalysis. BMJ. 313:1291–1296. Alund M, Larsson S (1990). Three-dimensional analysis of neck motion: a clinical method. Spine. 15(2):87–91. AMA: American Medical Association (1998). Legal Issues: Informed Consent [web page]; posted Sept. 1998; updated March 2007. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/4608.html. (Accessed 04/01/2007.) AMA: Association of American Medical Colleges, Report VII. Contemporary Issues in Medicine: Musculoskeletal Medicine Education Medical School Objectives Project, page 4 2005; http://www.aamc.org/meded/msop/msop7.pdf – accessed 3/23/07. American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Aminoff MJ (1996). Historical Perspective Brown-Séquard and His Work on the Spinal Cord. 21(1):133–140. An HS (1998). Synopsis of Spine Surgery. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 142–144. An HS, Seldomridge JA (2006). Spinal infections: diagnostic tests and imaging studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 444:27–33. Andersson Gunnar BJ, Linda Cocchiarella. Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, Fifth Edition, American Medical Association Press; 2000. Andrews JR, Carson WG Jr, McLeod WD (1985). Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med. 13(5):337–341. Andriacchi LP, Schulz AB, Betrytsko TB, Galente IO (1974). A model for studies of mechanical interactions between the thoracic spine and rib cage. J Biomech. 7:497. Angelides AC, Wallace P (1976). The dorsal ganglion of the wrist: its pathogenesis, microscopic anatomy and surgical treatment. J Hand Surg. 1:228. Angelides AC, (1999). Ganglions of the Hand and Wrist. In: Green DP, ed. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2171–2183. Ansell B (1980). Rheumatic Disorders in Childhood. London: Butterworths. Antinnes JA, Dvořák J, et al. (1994). The value of functional computed tomography in the evaluation of soft-tissue injury in the upper cervical spine. Eur. Spine J. 3:98–101. Arlen A (1977). Die “paradoxe Kippbewegung des Atlas” in der Funktionsdiagnostik der Halswirbelsäule. Manuelle Med. 15:16–22. Arlen AL (1990). Metameric medicine and atlas therapy. In: Paterson JK, Burns L, eds. Back Pain: An international Review. Dordrecht, Holland: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 212–226. Assendelft WJ., Morton SC, Yu EI, Suttorp MJ, Shekelle PG (2004). Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD 000447. Auteroche P (1983). Innervation of the zygapophyseal joints of the lumbar spine. Anat Clin. 5:17–28. Bagnall KM, Ford DM et al. (1984). The histochemical composition of human vertebral muscle. Spine. 9:470–473. Baker AS, Ojemann RG, Swartz MN, Richardson EP Jr (1975). Spinal epidural abcess. N Engl J Med. 293:463–468. Baker JG, Granger CV, Ottenbacher KJ (1996). Validity of a brief outpatient functional assessment measure. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 75:356–363. Bakke S (1931). Röntgenologische Beobachtungen über die Bewegungen der Halswirbelsäule. Acta Radiol. 13(Suppl):1–72. Barbour A (1995). Caring for Patients: A Critique of the Medical Model, Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Press; 1995a. Barnard RJ, Edgerton VR, et al. (1971). Histochemical, biochemical and contractile properties of red, white, and intermediate fibers. Am J Physiol. 220:410–414. Baron R (2000). Peripheral neuropathic pain: from mechanisms to symptoms. Clin J Pain. 16:S 12–20. Barr JS (1977). Lumbar disk lesions in retrospect and prospect [Address tape-recorded May 1961]. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (129; Nov-Dec):4–8 Barré J, Lieou Y (1928). Le syndrome sympathique cervicale postéreur. Strasbourg: Schuler and Mink. Bärtschi W (1949). Migraine Cervicale. Das encephale Syndrom nach Halswirbeltrauma. Bern: Huber. Beal MC (1982). The sacroiliac problem: review of anatomy, mechanics and diagnosis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 81(10):667–79. Beal M (1983). Palpatory testing for somatic dysfunctions in patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 82(11):822–831. Beal M, Dvořák J (1984). Palpatory examination of the spine: A comparison of the results of two methods. Relationship of segmental (somatic) dysfunction to visceral disease. J Manual Med. 1:25–32. Benett GJ, Ruda MA, Gobel S, Dubner R (1982). Enkephalin immunoreactive stalked cells and lamina II b islet cells in cat substantia gelatinosa. Brain Res. 240:162–166. Bengtsson A, Henriksson K, et al. (1986). Reduced high-energy phosphate levels in the painful muscles of patients with primary fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 29(7):817–821. Bengtsson A, Henriksson K (1989). The muscle in fibromyalgia: review of Swedish studies. J Rheum. 16(Suppl 19):144–149. Benini A (1981). Claudicatio intermittens der Cauda equine. Praxis. 12:504–510. Bennett RM (1989). Beyond fibromyalgia: ideas on etiology. J Rheum. 16(Suppl. 19):185–191. Bensen WG, Fiechtner JJ, McMillen JI, et al. (1999). Treatment of osteoarthritis with celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor: a randomized control trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 74:1095–1105. Berger M (1990). Cervicomotographie: Eine neue Methode zur Beurteilung der HWS-Funktion. Stuttgart, Ferdinand Enke Verlag. Bergman GJD, Winters JC, Groenier KH, et al. (2004). Manipulative therapy in addition to usual medical care for patients with shoulder dysfunction and pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 141(6):432–439. Bergmark A (1989). Stability of the lumbar spine. A study in mechanical engineering. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 230:1–54. Bernard TN Jr, Cassidy JD (1991). The sacroiliac joint syndrome—pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. In: Frymoyer JW, ed. The Adult Spine: Principles and Practice. New York: Raven Press; 2107–2130. Bernhard W (1976). Kraniometrische Untersuchungen zur funktionellen Morphologie des oberen Kopfgelenks beim Menschen. Gegenbaurs Morph Jb. 122:497. Besson JM (1999). The neurobiology of pain. Lancet. 353:1610–1615. Biedermann F (1954). Nervenleiden und Nervenschmerzen. Ihre Behand-lung und Heilung durch Handgriffe. Von Dr. med. O. Naeglie. Ulm: Haug. Biemond A, de Jong J (1969). In cervical nystagmus and related disorders. Brain. 92:437. Billeter R, Heizmann CW, Howald H, Jenny E (1981). Analysis of myosin light and heavy chain types in single human skeletal muscle fibers. Eur J Biochem. 116:389–395. Billeter R., Hoppeler H (1995). Grundlagen der Muskelkontraktion. Schweiz Z Med Traumatol. 2:6–20. Bird HA, Esselinckx W, Dixon AS, Mowat AG, Wood PH (1979). An evaluation of criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis. 38(5):434–439. Bird HA, Leeb BF, Montecucco CM, et al. (2005). A comparison of the sensitivity of diagnostic criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis. 64(4):626–629. Bischofberger R (1978). Resektionsarthroplastik am Daumensattelgelenk. Analyse der Resultate. In: Segmüller G (ed.). Das Mittelhandskelett in der Klinik. Bern: Huber; 112–117. Bjordal JM, Ljunggren AE, Klovning A, Slørdal L (2004). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, in osteoarthritic knee pain: meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ. 329(7478):1317. Blau JN, Loque V (1978). The natural history of intermittent claudication of the cauda equine. Brain. 101:211–222. Blumer D, Heilbronn M (1982). Chronic pain as a variant of depressive disease. The pain-prone disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 170:381–406. Bogduk N, Aprill C (1993). On the nature of neck pain, discography and cervical zygapophysial joint blocks. Pain. Aug; 54(2):213–217. Bogduk N, Marsland A (1986). On the concept of third occipital headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 49(7):775–780. Bogduk N (1992). The anatomical basis for cervicogenic headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 15(1):67–70. Bogduk N (1997). Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum, 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone:1997; 101–125. Boissevain M, McCain G (1991). Toward an integrated understanding of fibromyalgia syndrome. I. Medical and pathophysiological aspects. Pain. 45:227–238. Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. (2000). VIGOR Study Group. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520–1528. Bonica JJ, Albe-Fessard D (1980). Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. New York: Raven Press. Borgbjerg FM, Nielsen K, Franks J (1996). Experimental pain stimulates respiration and attenuates morphine-induced respiratory depression: a controlled study in human volunteers. Pain. 64:123–128. Borovansky L (1967). Soustavna Anatomie Cloveka, 3 rd ed. Prague: SZN. Bourdillon JF (1973). Spinal Manipulation. London: William Heinemann Medical Books; 1–13. Bowen V, Cassidy JD (1981). Macroscopic and microscopic anatomy of the sacroiliac joint from embryonic life until the eight decade. Spine. 6:820–827. Brealey S, Coulton S, Farrin A, et al. (2004a). United Kingdom Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: cost effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ. 329(7479):1381–1385. Brealey S (2004b). United Kingdom Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ 2004;329:1377–1380. Brodal A (1981). Neurological Anatomy in Relation to Clinical Medicine, 3rd ed. Oxford; Oxford University Press. Brooke MH, Kaiser KK (1970). Muscle fiber types: how many and what kind? Arch Neurol. 23:369–379. Brooke MH, Kaplan H (1972). Muscle pathology in rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica and polymyositis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 94:101–117. Brown MG, Goodwin GM, Matthews PBG (1970). The persistence of stable bonds between actin and myosin filaments of intrafusal muscle fibers following their activation. J Physiol Lond. 210:9–10. Brown-Séquard CE (1869). Lectures on the physiology and pathology of the nervous system, and on the treatment of organic nervous system, and on the treatment of organic nervous affections. Lecture II. On organic affections and injuries of the spinal cord producing some of the symptoms of spinal hemiplegia. Lancet. 1:1–3, 219–20, 703–5, 873–6. Brügger A (1962). Pseudoradikuläre Syndrome. Acta Rheum. 19:1. Brügger A (1965). Pseudoradikuläre Syndrome des Stammes. Bern: Huber. Brügger A (1977). Die Erkrankungen des Bewegungsapparates und seines Nervensystems. Stuttgart: Fischer. Brune K, Hinz B (2001). Nichtopioidanalgetika (antipyretische Analgetika und andere). In: Zenz M, Jurna I, eds. Lehrbuch der Schmerztherapie. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 233–253. Brunner C, Kissling R, Jacob HA (1991). The effects of morphology and histopathologic findings on the mobility of the sacroiliac joint. Spine. 16(9):1111–1117. Buckwalter JA, Stanish WD, Rosier RN, et al. (2001). The increasing need for nonoperative treatment of patients with osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop. 385:36–45. Buerger PC, Vogel FS (1982). Surgical Pathology of the Nervous System, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley. Buerger AA (1983). Experimental neuromuscular models of spinal manipulative techniques. Manual Medicine. 1:10–17. Buetti-Bäuml C (1954). Funktionelle Roentgendiagnostik der Halswirbelsäule. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiet der Röntgenstrahlen vereinigt mit Röntgenpraxis. Archiv und Atlas. 70:19–23. Burke RE, Levine DN, et al. (1971). Mammalian motor units: physiological–histochemical correlation in three types in cat gastrocnemius. Science. 174:709–712. Bush K, Hillier S (1991). A controlled study of caudal epidural injection of triamcinolone plus procaine for the management of intractable sciatica. Spine. 16(5;2523):572–575. Cailliet R (1977). Soft Tissue Pain and Disability. Philadelphia: FA Davies. Carpenter S, Karpati G (1984). Pathology of Skeletal Muscle. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 460–470. Casey AT (1995). Vital Reconstruction in Rheumatoid Arthritis. In: Baumgartner H, et al., eds. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Current Trends in Diagnosis, Conservative Treatment and Surgical Reconstruction. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme. Cashion EL, Lynch WJ (1979). Personality factors and results of lumbar disc surgery. Neurosurgery. 4:141–145. Catterall A (1973). Legg–Calvé–Perthes Disease. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. Caviezel H (1976). Klinische Diagnostik der Funktionsstörung an den Kopfgelenken. Schweiz Rundsch Med Praxis. 65:1037. Chandrasekharan NV, Dai H, Roos KL, et al. (2002). COX-3, a cycloexygenase-1 variant inhibited by acetaminophen and other analgesic/anti-pyretic drugs: cloning, structure, and expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 99:13926–13931. Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Loeser JD, et al. (1994). An international comparison of back surgery rates. Spine. 19:1201–1206. Chiradejnant A, Maher CG, et al. (2003). Efficacy of “therapist-selected” versus “randomly selected” mobilisation techniques for the treatment of low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother. 49(4):233–241. Chomiak J (1993). Morphological Basis of Electrogymnastics of the M. Vastus Madialis and Lateralis. Acta Chir. Orthop. Traum. Cech. 60:334–339. Chomiak J, Dvorak J, Antinnes J, Sandler A (1995). Motor evoked potentials: appropriate positioning of recording electrodes for diagnosis of spinal disorders. Eur Spine J. 4(3):180–5. Chomiak J, Dungl P, Grim M (2003). Reconstruction of Elbow Flexion in Patients with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita with M. Pectoralis Major. Part II – Results of Electromyographic and Histological Examinations. Acta Chir. Orthop. Traum. Cech. 70:25–30. Chuang TY, Hunder GG, Ilstrup DM, Kurland LT (1982). Polymyalgia rheumatica: a 10-year epidemiologic and clinical study. Ann Intern Med. 97(5):672–680. Cocchiarella L, Andersson GBJ, eds. (2001). Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 5th ed. Chicago, IL: AMA Press. Codman E (1934). The Shoulder: Rupture of the Supraspinatus Tendon and Other Lesions in or About the Subacromial Bursa. Boston: Miller; 234–245. Cohen MM, Penman S, Pirotta M, Costa CD (2005). The integration of complementary therapies in Australian general practice: results of a national survey. J Alternative Complementary Med. 11(6):995–1004. Colachis SC et al. (1963). Movements of the sacroiliac joint in the adult male. A preliminary report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 44:490. Cole A, Heithoff KB, Herzog RJ (2003). In: Cole AJ, Herring SA, eds. The Low Back Pain Handbook—A Guide for the Practicing Physician, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Hanley and Belfus; 219–261. Cooper S, Daniel PM (1963). Muscle spindles in man, their morphology in the lumbricals and the deep muscles of the neck. Brain. 86:563–586. Cotterill J (1887). Condition of stiff great toe in adolescents. Edinburgh Med J. 33:459–462. Cramer A (1965). Iliosakralmechanik. Asklepios. 6:261–262. Cramer A, Doering J, et al. (1990). Geschichte der manuellen Medizin. Berlin: Springer. Crisco JJ III, Panjabi MM, Dvořák J (1991). A model of the alar ligaments of the upper cervical spine in axial rotation. J Biomech. 24(7):607–614. Cumming WJK, Fulthorpe JJ, Hudgson P, Mahon M (1994). Color Atlas of Muscle Pathology. London: Mosby-Wolfe. Cummings SR, Black DM, et al. (1993). Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. The Stude of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet. 341:72–75. Curatolo M, Bogduk N (2001). Pharmacologic pain treatment of musculo-skeletal disorders: current perspectives and future prospects. Clin J Pain. 17:25–32. Cyriax J (1938). Rheumatic headache. Br Med J. 2:1367–1368. Cyriax J (1984). Textbook of Orthopedic Medicine, vol. 2, 11th ed. London: Baillière-Tindall. Davis P, Lente BC (1978). Evidence for sacroiliac disease as a common cause of low backache in women. Lancet. 2:496–497. De Gowin EL, De Gowin RL (1981). Bedside Diagnostic Examination. New York: MacMillan; 36–37. De Jong PT, de Jong JM, Cohen B, Jongkees LB (1977). Ataxia and nystagmus induced by injection of local anesthetics in the neck. Ann Neurol. 1(3):240–246. De Quervain F (1895). Über eine Form von chronischer Tendovaginitis. Corresp Blatt Schweizer Arzte. 25:389–394. De Sèze C, Djian A, et al. (1951). Etude Radiologique de la dynamique cervical dans le plain sagittal. (Une contribution radiophysologique a l’étude pathogenique des artheoses cervicales). Revue du rhumatisme. 18:37–46. Dejung B (1985). Iliosacralblockierung—eine Verlaufstudie. Manuelle Med. 23:109–115. Dejung B (1987). Die Verspannung des M. iliacus als Ursache lumbosacraler Schmerzen. Manuelle Med. 25:73–81. Dejung B (1988). Triggerpunkt- und Bindegewebsbehandlung – neue Wege in Physiotherapie und Rehabilitationsmedizin. Physiotherapeut 6:3–12. Dejung B (1999). Die Behandlung unspezifischer chronischer Rückenschmerzen mit manueller Triggerpunkt- Therapie. Manuelle Med. 37:124–131. Dejung B (2006). Triggerpunkt-Therapie. Die Behandlung akuter und chronischer Schmerzen im Bewegungsapparat mit manueller Trigger-punkt-Therapie und Dry Needling. 2nd ed. Bern: Huber. Delmas A (1950). Fonction sacroiliaque et statique du corps. Rev du Rhumatisme. 9:475–481. Denson D, Katz J (1992). Nonsteroidal anti-inflamatory agents. In: Raj PP, ed. Practical Management of Pain, 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby. Depreux R, Mestdagh H (1974). Anatomie fonctionelle de l’articulation sousoccipitale. Lille Méd. 19:122–128. Derogatis LR, Melisarotos N (1983). The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 13:595–605. Deyo RA (1993). Practice variations, treatment fads, rising disability: Do we need a new clinical research paradigm? Spine 15. Deyo RA (2004). The role of outcomes and how to integrate them into your practice. In: Herkowitz H, Dvořák J, Bell G, Nordin M, Grob D, eds. The Lumbar Spine, 3 rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 139–148. Dias R, Chandrasenan R, Rajaratnam V, Burke F. Basal Thumb Arthritis, Postgraduate Medical Journal 2007;83:40–43; doi:101136/pgmj. 2006046300; accessed 04/18/2007. Dickenson AH (1995). Spinal cord pharmacology of pain. Br J Anaesth. 75:193–200.

Introduction

) and phasic (

) and phasic ( ) muscles.

) muscles.

Exercise Section

Stretching of Shortened Muscles

Strengthening of Weak Muscles (Figs. 19.22–19.31)

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree