History and Physical Examination

Hal David Martin

Ian James Palmer

Munif Hatem

Introduction

The anatomy of the human hip joint has been described by centuries of anatomists from Galen (121–201 CE) to Vesalius (1555) and Albinus (1749). Medical books written in the early 1800s began discussions of hip joint pathoanatomy. The late 1800s brought about medical journals such as the British Medical Journal, the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, and the Journal of the American Medical Association providing publications about congenital dislocation, angular deformities, amputation, femoral osteotomy, excision, and fibrous ankylosis. The invention of the x-ray in 1895 propelled the study of hip joint pathology into the 1900s with additional journals and increased publications. Topics included osteoarthritis, osteotomy, arthroplasty, roentgenographic studies, Perthes disease, and embryology by historic authors such as Ober, Freiberg, Stinchfield, Boscoe, Legg, Calvé, Perthes, and Pauwels. By the late 1900s, research proliferated covering the embryology, anatomy, and biomechanics of the hip joint and could be separated into categories of osteochondral, capsulolabral, musculotendinous, and neurovascular. Clinical evaluation maneuvers or tests have been developed assessing each of these categories: osteochondral by Harris and Ganz, capsulolabral by McCarthy and Philippon, musculotendinous by Thomas and in the Polio era by Ober, and neurovascular by Freiberg and Pace. As in prior times of technologic advancement, hip arthroscopy and open surgical techniques have progressed allowing for a better understanding of the complex hip anatomy and biomechanics. The clinical examination of the hip continues to evolve.

The understanding of anatomy and biomechanics of each system; the osteochondral, capsulolabral, musculotendinous, and neurovascular; are dependent on a comprehensive physical examination of the hip. Ideally there would be one physical examination test with one exclusive diagnosis; however, each system is interrelated with the others which raises the complexity in interpreting a single test. A nonlinear data process may be required to obtain a thorough understanding of a complex system (1). The physical examination is critical and must be collaborated to radiographic and diagnostic tests to create this four-system analysis. For example, asymptomatic patients often present abnormal hip imaging studies, which can be confirmed by the history and physical examination alone. Pathologic conditions may exist in a single layer or in multiple layers requiring a standardized examination to be followed. The establishment of a group of diagnostic tests as the background on which to cast the light of the pathologic condition is a key in the recognition of any complex pattern. This concept was demonstrated by the review of the Multicenter Arthroscopy of the Hip Outcomes Research Network (MAHORN) group (2). All members utilized a standardized set of tests in the same order, independent of history, to assess a variety of pathologic conditions and to establish the pathologic pattern. Consistent terminology of the examination is needed to eliminate international variances. A comprehensive standardized battery of physical examination tests and techniques will provide reliability and lead to an accurate diagnosis in all layers of the hip.

The Layers Approach to Hip Evaluation

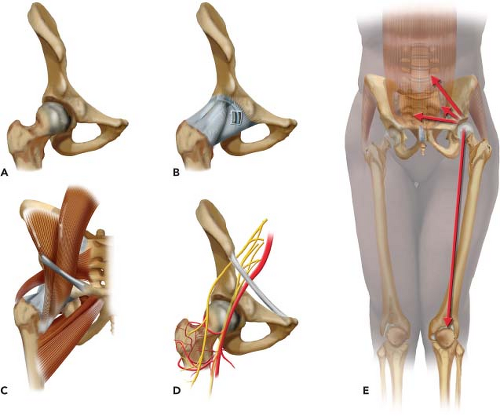

The history and physical examination of the hip are a comprehensive assessment of four distinct layers (3): osteochondral; capsulolabral; musculotendinous; and neurovascular (Fig. 22.1). The relationship between the hip and adjacent joints represents the fifth layer, the kinematic chain. These layers interrelate in a static and dynamic fashion and hip symptoms can arise from pathologic conditions located in a single or multiple layers. A standardized clinical evaluation will allow for the identification of pathologic conditions occurring in each of the five layers (Table 22.1).

History

The diagnostic and treatment tools for hip disorders have substantially evolved over the past decade. New therapeutic options are available and the issue of choosing the best approach for each patient depends mainly on the patient expectations and goals. Therefore, the history is important not only to define the diagnosis, but also to choose the most appropriate option for each patient among the treatment alternatives (4).

A comprehensive history of the patient is obtained prior to the physical examination of the hip. The data collection points are common to other joints, such as the knee and shoulder. The chief complaint is documented including the

date of onset, presence or absence of trauma, and mechanisms of injury. Pain is characterized according to location, severity, and factors that increase or decrease the pain. Knee or lumbar referred pain is a frequent accompanying symptom of hip pathology and should also be investigated.

date of onset, presence or absence of trauma, and mechanisms of injury. Pain is characterized according to location, severity, and factors that increase or decrease the pain. Knee or lumbar referred pain is a frequent accompanying symptom of hip pathology and should also be investigated.

Figure 22.1. Illustration of the five layers compounding the hip. A: Osteochondral B: Capsulolabral C: Musculotendinous D: Neurovascular E: Kinematic chain. |

Treatment to date must be clearly defined, including all conservative and surgical therapies. The patient’s functional status is assessed and current limitations are detailed, which may involve getting in or out of a bathtub or car, activities of daily living, jogging, walking, and/or climbing stairs. It is also necessary to identify related symptoms of the spine, abdomen, and lower extremity. Limitation of hip motion can lead to secondary problems in lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint, and pubic inguinal musculotendinous structures (5,6,7,8), representing the fifth layer or kinematic chain. Knee ligament injury can also be associated to restrict hip mobility (9). The presence of back pain and coughing or sneezing exacerbation help rule out thoracolumbar problems. Abdominal pain, anorectal and genitourinary complaints, and menses-related symptoms indicate intrapelvic or abdominal pathologies, which may coexist with hip problems. In addition, night pain, sitting pain, weakness, numbness, or paraesthesia in the lower extremity may suggest neural compression, which can be located at lumbar spine, inside the pelvis or within the subgluteal space. The following items must additionally be addressed: past injuries; childhood or adolescent hip disease; ipsilateral knee disease; suggestive history of inflammatory arthritis; and risk factors for osteonecrosis.

Table 22.1 Example of a Hip-layered Diagnosis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hip pain often stems from some type of sports-related injury, mainly with rotational sports, such as golf, tennis, ballet, and martial arts. Five to six percent of adult sports injuries originate in the hip and pelvis (10). Athletes participating in rugby and martial arts have also been reported to have an increased incidence of degenerative hip disease (11). Documentation of sports activities can help determine the type of injury and guide the treatment considering the patient’s goals and expectations. A complete review of the history is given in Table 22.2.

Table 22.2 Complete Review of Patient History | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 22.3 Characteristics of Questionnaires Used for Hip Evaluation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Before the medical consult, a questionnaire is utilized to score the patient’s hip status. Different questionnaires have been used to assess patient hip joint function and related pain (Table 22.3). The Harris hip score (HHS) is the most documented hip score and was first described to evaluate patients with mold arthroplasty (12) and has been modified for more current use in hip arthroscopy (13). As the hip joint questionnaires have evolved, the functional assessment has become more important and self-administered questionnaires are preferred rather than observer administered (14). Recently, the MAHORN group has validated the International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33) (15). Developed through an international

multicenter study, the iHOT-33 is a self-administered questionnaire and its target population is active adult patients with hip pathology. While the iHOT-33 was developed for research purposes, a short form (iHOT-12) (16) was also described for use in routine clinical practice. The Short Form 36 (SF-36) (17) and 12 (SF-12) (18) are questionnaires used for general health survey and are sometimes associated with the more hip-specific evaluation tools.

multicenter study, the iHOT-33 is a self-administered questionnaire and its target population is active adult patients with hip pathology. While the iHOT-33 was developed for research purposes, a short form (iHOT-12) (16) was also described for use in routine clinical practice. The Short Form 36 (SF-36) (17) and 12 (SF-12) (18) are questionnaires used for general health survey and are sometimes associated with the more hip-specific evaluation tools.

The Physical Examination of the Hip

The hip is responsible for distributing weight between the appendicular and axial skeleton, and is the joint from which most human motion is initiated and executed. The forces through the hip joint can reach three to five times the body weight during running and jumping (22). Hip joint function determines and influences quality of life, ability to work, activities of daily living, and function in society. The economic and social impact of hip dysfunction is underappreciated and the physical examination understanding is critical in differentiating normal from pathologic conditions.

A consistent examination is performed to screen the lumbar spine, abdominal, neurovascular, and neurologic systems, and to find the comorbidities that exist with complex hip pathology. Access for exposure and patient comfort with loose-fitting clothes about the waist is helpful during the hip examination. An assistant to record the examination on a standardized written form aids in accurate documentation and thoroughness, especially when first starting a comprehensive hip evaluation (Fig. 22.2). Each examination or physical evaluation has a specific method of being performed, although the technique of physical examination is dependent on the examiner’s experience and efficiency. The MAHORN group common tests form the core of a multilayered hip evaluation (2).

Standardization improves the physical examination reliability (23). The most efficient order of examination begins with standing tests followed by seated, supine, and lateral tests, ending with prone tests (24,25). Therefore, that sequence of examination positions will be utilized in this chapter. In each position, the maneuvers will be presented in the following order: inspection, palpation, femoroacetabular congruence tests, other specific tests, and posterior extra-articular hip pain tests. In total, 32 tests or group of maneuvers will be described, forming the standard hip physical examination similar to that of the knee and shoulder (26,27) Of these maneuvers, 16 assess the osteochondral layer, 13 the capsulolabral layer, 11 the musculotendinous layer, 7 the neurovascular layer, and 5 the kinematic chain. Sixteen maneuvers or group of maneuvers evaluate more than one layer. This examination may take as long as 8 minutes, however it can be completed in less time depending on the examiner’s practice. Finally, a summary of the standardized femoroacetabular congruence tests will be presented followed by a description of snapping hip tests.

Figure 22.2. Assistant recording examination findings following a standardized form improves reliability and allows a complete five-layer examination. |

Standing Examination

In a standing position, a general point of pain is noted with one finger, and can usually help direct the examination. The groin region directs a suspicion of intra-articular problem. Lateral-based pain may be associated with intra- or extra-articular aspects. A characteristic sign of patients with intra-articular hip pain is the “C Sign” (28). The patient will hold his or her hand in the shape of a C and place it above the greater trochanter, with the thumb positioned posterior to the trochanter and fingers extending into the groin (28). This finding can be misinterpreted as lateral soft tissue pathology, such as trochanteric bursitis or iliotibial band contracture; however, the patient is often describing deep interior hip pain (28). The shoulder and iliac crest heights are noted to evaluate leg-length discrepancies (Table 22.4). Forward bending of

the trunk is performed to evaluate the lumbar spine and to differentiate structural from nonstructural scoliosis, recording the degree of trunk flexion (Fig. 22.3). The lumbar lordosis is also observed. Incremental wooden blocks placed under the short side foot help in orthotic considerations. General body habitus is assessed and generalized joint laxity is diagnosed when three or more of the following tests are positive (Fig. 22.4): (1) passive dorsiflexion of the little finger beyond 90 degrees; (2) passive opposition of the thumb to the flexor aspect of the forearm; (3) hyperextension of the elbow beyond 10 degrees; (4) hyperextension of the knee beyond 10 degrees; (5) forward bending of the trunk so that the palms of the hands rest easily on the floor (29).

the trunk is performed to evaluate the lumbar spine and to differentiate structural from nonstructural scoliosis, recording the degree of trunk flexion (Fig. 22.3). The lumbar lordosis is also observed. Incremental wooden blocks placed under the short side foot help in orthotic considerations. General body habitus is assessed and generalized joint laxity is diagnosed when three or more of the following tests are positive (Fig. 22.4): (1) passive dorsiflexion of the little finger beyond 90 degrees; (2) passive opposition of the thumb to the flexor aspect of the forearm; (3) hyperextension of the elbow beyond 10 degrees; (4) hyperextension of the knee beyond 10 degrees; (5) forward bending of the trunk so that the palms of the hands rest easily on the floor (29).

Table 22.4 Summarized Standing Examination Assessment | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gait abnormalities often help detect hip pathology (30,31), since normal functioning of all five hip layers is fundamental to a normal gait (Fig. 22.5). The patient is taken into the hallway to observe a full gait of six to eight stride lengths. Key points of gait evaluation include foot progression angle (FPA), pelvic rotation, stance phase, stride length, and arms swing. The FPA is usually seven degrees of toeing-out (30). It is influenced by the rotational profile of the hip, femur, tibia, and talus (32), associated to muscular and capsular effects. The whole limb, including osseous and soft tissues, must be considered when evaluating any FPA abnormality. Increased femoral version can cause an internally rotated FPA, but it may be balanced by tibial lateral torsion

(33) or deficient medial hip rotators. The knee and thigh are observed simultaneously to assess any rotatory parameters. The knee may want to be held in internal or external rotation to allow proper patellofemoral joint alignment, but may produce a secondary abnormal hip rotation. This abnormal motion is usually present in cases of severe increased femoral anteversion, precipitating a battle between the hip and knee for a comfortable position, which will affect the gait. In cases of a painful ambulation, note the anatomical location of the pain and at what point within the gait phase the pain is manifest. The arms swing during the gait should be also observed, since a normal gait encompasses arms movements coordinated with the lower limbs. During forward arm movement, the contralateral gluteus maximus is activated.

(33) or deficient medial hip rotators. The knee and thigh are observed simultaneously to assess any rotatory parameters. The knee may want to be held in internal or external rotation to allow proper patellofemoral joint alignment, but may produce a secondary abnormal hip rotation. This abnormal motion is usually present in cases of severe increased femoral anteversion, precipitating a battle between the hip and knee for a comfortable position, which will affect the gait. In cases of a painful ambulation, note the anatomical location of the pain and at what point within the gait phase the pain is manifest. The arms swing during the gait should be also observed, since a normal gait encompasses arms movements coordinated with the lower limbs. During forward arm movement, the contralateral gluteus maximus is activated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree