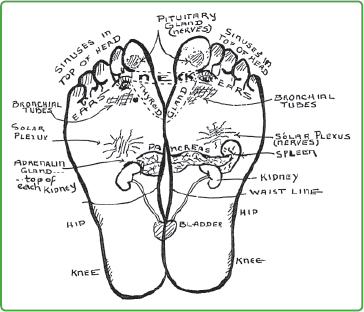

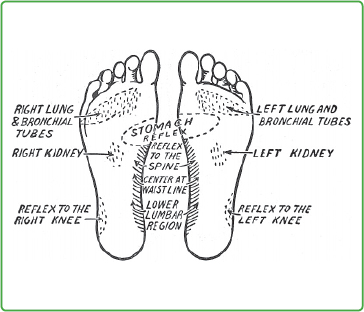

1 Historical Development of Foot Treatments Development of reflexotherapy of the feet (RTF) from its earliest beginnings to today probably followed a path similar to many other forms of treatment which are now generally accepted. There have always been people with special abilities whose instinct and intuition have told them what is needed for particular illnesses, because they are far more in touch with natural connections and cosmic laws. Over the centuries ancient knowledge regarding the healing powers of herbs, for example, developed into phytotherapy, while piercing certain points on the body with simple, pointed objects (already historically documented in ancient times) became acupuncture, and sharpened stones and metals used to perform internal procedures on people in earlier times marked the beginnings of surgery. The beginnings of foot treatments that are now practiced in the Middle East have already been substantiated by millennia-old Egyptian pictographs (Fig. 1.1), showing that the feet—as well as the hands—are well suited to treatment. In this regard the words of a high official may be approximately rendered as, “Cause me no pain!”—with the response, “I will conduct myself in such a way that you will praise me.” There are also records from the Far East of marks on the feet as a result of ancient ritual practices. These are frequently found on the soles of the feet of Buddhist statues, and it is likely that they were for the purposes of religious worship. For decades, however, a simple (and often very painful) treatment of the feet was performed as a folk remedy in various countries of the Far East, and this was probably the result of more recent Western principles. Since the last century evidence has also emerged from the Western world that the indigenous peoples of Central and North America treated their sick using points on the foot. Christine Issel (USA) researched the topic in depth, and in 1990 she compiled interesting evidence in her book Reflexology: Art, Science and History. The Cherokee Indians appear to be the only tribe for which there is evidence that they have continued using foot therapy until modern times. It is supposed that they acquired their knowledge from the Incas of South America. According to ancient sources, various physicians in Europe were already performing a kind of zone therapy in the Middle Ages. At the beginning of the last century, in a book Henry B. Bressler refers to a document in which around 1,582 physicians described treatment of areas of the hand and foot and the astonishing results they obtained in people who were sick. All this goes to show that from time immemorial the feet have been ascribed a major, multidimensional significance in many human cultures. In the first instance, anyone performing foot treatments today refers to Dr. William FitzGerald, an American ENT physician (1872–1942), who in 1917 published the book Zone Therapy with Dr. Edwin Bowers. No explicit reference is made, either in his literature or in former colleagues’ accounts, to the sources from which he developed his most important “tool,” viz. the division of the human body into 10 longitudinal zones. As FitzGerald also worked in London, Paris, and Vienna for several years, it is supposed that there he came across old European literature that accorded with this view. Another assumption is that he acquainted himself with the general principles of acupuncture while living in Europe and possibly stylized the 12 familiar main meridians to form 10 longitudinal zones. The basic concept of his work, which he discovered empirically through many years of private practice, was that all the strains and disorders of organs and tissues found in any 1 of the 10 longitudinal zones can be therapeutically influenced from the head downward to the hands and feet within this longitudinal zone. Regardless of where FitzGerald obtained his information and notwithstanding that his proposed treatments sometimes appeared bizarre (among other things, he used metal combs, clothes pegs, and thin wooden sticks), this 10-zone grid (Fig. 2.1) has continued to provide a reliable working model for our foot treatments up to the present day. It was also in FitzGerald’s book of 1917 that I found the first representation of organ zones on the foot. The historical literature reveals that in spite of a number of detractors, FitzGerald not only treated his own patients highly successfully in accordance with this tried and tested grid pattern, but he also provided practical training for physicians and therapists from different fields for many years. In a later document, one of his closest colleagues, Dr. George Starr White, describes how zone therapy was one of the best-known forms of therapy in the United States in 1925. The American masseuse Eunice Ingham (1888–1974) drew on these experiences in the early 1930s. Unlike FitzGerald, however, she did not treat various points on the human body but focused on the feet, through which the 10 body zones also pass. She developed a special treatment technique which she initially called “The Ingham Method of Compression Massage.” In 1938 she published the first written synopsis of her experiences under the title Stories the Feet Can Tell, and this was followed by her second book, Stories the Feet Have Told. Her work generated widespread interest under the term “Reflexology,” especially among lay people. Both her books were published in the United States as well as in many other countries, and her knowledge continues to be used as the basis for self-help and health maintenance by many health-conscious groups to this day. In 1958, as a 25-year-old nurse and therapeutic masseuse, I first read about foot treatment in E. Ingham’s book (see above). Since I had trained as a State Registered Nurse in England, the subject was of interest to me, not least because of the language, although its content initially seemed very strange. Above all, I found it implausible that improvements in a person’s condition could be achieved at far removed locations just by “applying pressure” to special points on the foot. However, therapeutic curiosity impelled me to examine the specified areas corresponding respectively to the patient’s symptoms. To my surprise, not only were they painful but treating them resulted in significant alleviation of the patient’s symptoms. Soon I was employing this new method almost exclusively. Owing to the fact that from the outset I was working with patients—and not, as occurs in the United States and other countries, with clients—the transition from well-being and prevention to therapy occurred almost of its own accord. In 1967 I began offering courses for specialists and regarded this training as supplementary for medical therapists with an interest in this area. Not until later did I realize that distinguishing RTF from the lay method made it relatively easy to employ RTF professionally in physical therapy practices, hospitals, and rehabilitation centers.

1.1 First Historical References

1.2 Developments in Modern Times

1.3 The Path from Reflexology to Reflexotherapy of the Feet

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine