| 1 | Historical Background |

“Aside from maintaining the greatest possible distance from the source of infection when drilling into the medullary cavity or removing the affected bone segment, a special dressing technique is used for immobilization and elevation of the involved extremity.”

This therapeutic advice is not from a current textbook, but was written by Johannes Scultetus (1595–1645), a surgeon from Ulm (Germany), who described this technique in his book Armantarium Chirurgicum, thus confirming that osteomyelitis has plagued mankind for many centuries.

The history of chronic bone infection actually goes back millions of years. Findings from the age of dinosaurs display obvious signs of inflammatory processes in fractured dinosaur vertebrae. Remainders of hominid skeletons also show lesions indicating the presence of osteomyelitic processes. The approximately 500000-year-old femur of Java man (Homo erectus) shows possible signs of fracture healing complicated by osteomyelitis.

Cases are even described among Neanderthals (approximately 50000 years ago), like the case of osteomyelitis of the clavicle found in the Shanidar region of Iraq. The Smith papyrus from Ancient Egypt (approximately 1550BCE) is considered the oldest written report of a bone disease. It also contains descriptions of bone infections. Radiographs of Egyptian mummies identified remains of osteomyelitic processes.

In ancient times the Greek physician Hippocrates recommended “conservative therapy” of affected skeletal regions. In his opinion, necrotic bone and soft tissue should not be removed, but should be left to spontaneous rejection. He attributed great importance to treatment by rest and immobilization of the affected limb. Already in the first century the Roman physician Celsus recognized the importance of debridement and of vital bone tissue. In his view, one should only stop scraping the bone when blood appeared, which he considered to be a sign of vital bone tissue.

During the following centuries little new knowledge appeared in the theory and treatment of bone infections. In the 16th century, Paracelsus (approximately 1493–1541) recommended a consistently hygienic procedure to keep the wound free from contamination.

The history of posttraumatic osteomyelitis is closely connected with combat surgery, since the invention of firearms led to a multitude of open fractures caused by gunshot wounds. For example, Baron Larrey (1766–1842), a military surgeon in the Napoleonic army, reported that amputation was the preferred therapeutic treatment of gunshot wounds with bone involvement and performed more than 300 amputations on wounded soldiers in one day during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia.

John Hunter (1728–1793) developed the first scientifically based concepts about the origin of sequestra in bone infections based on experiments performed in his animal laboratory. These theories can be considered the first milestone in understanding the pathophysiologic processes in osteomyelitis.

Leading works by Semmelweis, Pasteur, Koch, and Lister from the middle of the 19th century led to pioneering conclusions in the theory and treatment of infection. The observations of Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865) in the 1840s that not only body parts left over from autopsies, but also pus on physicians’ hands, were responsible for puerperal sepsis, are considered the origins of antisepsis. Twenty years later Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) succeeded in discovering bacteria and identifying them as the cause of disease. He pinpointed staphylococci as the causative agent in osteomyelitis. Joseph Lister (1827–1912) asked himself why open fractures usually produced pus, but closed fractures did not, and what the critical difference was between an open and a closed fracture. Lister’s familiarity with the work of his contemporary Pasteur induced him to combat the organisms responsible for wound and bone infections to prevent them occurring. He used carbolic acid (phenol) for the disinfection of contaminated wounds in the 1860s. Carbolic acid was applied directly to the wound and was also used to saturate the dressings applied afterwards, which led to the term “Lister dressing.”

The discovery of penicillin by the Scot, Alexander Flemming (1881–1955), in 1928 revolutionized the whole field of medicine, as well as the treatment possibilities for osteomyelitis. In the 1930s, hematogenous osteomyelitis was responsible for 75% of all bone infections, which before the era of antibiotics led to a mortality rate of 20%. The introduction of penicillin reduced this mortality rate to less than 3%.

Lorenz Böhler (1885–1973), founder of the field of orthopedic trauma surgery, recognized the danger of osteomyelitis in the operative treatment of fractures, especially when placing internal fracture fixation devices, and issued the following warning in 1930: “The most dangerous innovation in the treatment of fresh fractures is the fundamental operative approach, especially when practiced by novices, without the appropriate indication and with insufficient asepsis and inadequate materials.” He emphasized the importance of disinfecting both instruments and hands, which had already been called for by Semmelweis, Pasteur, and Lister. Robert Koch (1843–1910) ushered in modern sterilization by recommending the use of heat and steam, which is safer and more reliable than disinfection with acid.

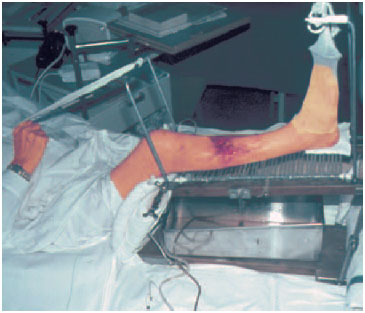

In the late 1950s Hans Willenegger (1910–1998) modified the practice of irrigation drainage (Fig. 1.1), which had been in use since World War I, by adding chloramphenicol to the irrigation fluid and draining it through a second drain. This often led to better healing of chronic osteomyelitis. This procedure, however, required intensive nursing care, and patients had to remain in bed beyond the treatment duration, which lasted several weeks.

In 1970 Hans-Wilhelm Buchholz, a surgeon with extensive knowledge for that time in the field of total joint prosthesis, published a paper in which he reported a reduction in the rate of infections occurring with the placement of hip prostheses when the antibiotic gentamicin was added to the bone cement consisting of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA).

Klaus Klemm (1932–2000), a surgeon from Frankfurt, Germany, adapted this concept by forming small beads molded from the malleable gentamicin-PMMA cement. After several experiments, in 1972 he first placed these in the medullary space of a patient’s infected bone following classical surgical debridement. This was the birth of the concept of operative local antibiotic treatment. At the same time, Verhoeve and colleagues used gentamicincement seals for local antibiotic treatment. This, however, proved unsuccessful. Until 1976 Klemm produced his gentamicin-PMMA beads himself in the operating theater and achieved very good treatment results. In November of the same year, Merck Pharmaceuticals (Darmstadt, Germany) overcame the fundamental problems in the industrial production of these beads. Klemm thus introduced a new, albeit controversial, therapeutic concept which demonstrated unprecedented treatment success combined with patient comfort. Patients were no longer confined to their bed, and the treatment duration was considerably reduced in comparison to the suction/ irrigation drainage procedure.

Despite available therapeutic possibilities, chronic osteomyelitis still presents both the patient and the doctor in charge with a serious situation. The increasing number of multidrug-resistant organisms over the past years, above all in bone and soft-tissue defects, complicates therapy considerably and calls for united efforts on the part of involved physicians, microbiologists, and industry to come up with new antimicrobial substances and/or new therapeutic approaches.

Fig. 1.1 Chronic osteomyelitis, former treatment scheme applying mechanical toilet.